- Home

- Harry Harrison

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 Page 8

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 Read online

Page 8

“What of your friend? What can you do?”

“I can pull teeth,” replied Hund unexpectedly.

The half dozen men still standing round had grunted in amusement. “Tenn draga,” remarked one of them. “That er ithrott.”

“He says, ‘To draw teeth, that is an accomplishment,’ ” Thorvin translated. “Is it true?”

“It is true,” supplied Shef for his friend. “He says it is not strength you need. It is a twist of the wrist—that, and knowing how the teeth grow. He can cure fevers too.”

“Tooth-drawing, bone-setting, fever-curing,” said Thorvin. “There is always trade for a leech among women and warriors. He can go to my friend Ingulf. If we can get him there. See, you two, if we can get to our own places in the camp—my forge, Ingulf's booth—we may be safe. Till then—” He shook his head. “We have many ill-wishers. Some friends. Will you take the risk?”

They had followed him mutely. But wisely?

As they came toward it, the camp looked more and more formidable. It was enclosed by a high earth rampart, with a ditch outside it, each side at least a furlong in length. Lot of work in that, thought Shef. Lot of spadefuls. Did that mean they were going to stay a long time, that they thought it worth doing so much? Or was it a matter of course to the Vikings? A routine?

The rampart was crowned with a stockade of sharpened logs. A furlong. Two hundred and twenty yards. Four sides—No, from the lay of the land Shef realized suddenly that one side of the camp was bounded here by the river Stour. On that side he could even see prows projecting into the sluggish stream. He was puzzled—until he realized that the Vikings must have pulled their ships, their most precious possessions, up on the mudflats there, then grappled them together so that they themselves formed one wall of the enclosure. Big. How big? Three sides. Three times two hundred and twenty yards. Each log in the stockade maybe a foot wide. Three feet to a yard.

Shef's mind, as it so often did, tried to grapple with the problem of numbers. Three times three times two hundred and twenty. There must be a way to know the answer to that, but this time Shef could see no shortcut to finding it. It was a lot of logs, anyway, and big ones too, cut from trees hard to find down here on the flats. They must have brought the logs with them. Dimly, Shef began to discover an unfamiliar notion. He knew no word for it. Making plans, perhaps. Planning ahead. Thinking things out before they happened. No detail was too small for these men to trouble with. He suddenly realized that they did not think war was only a matter of the spirit, of glory and speeches and inherited swords. It was a trade, a matter of logs and spades, preparation and profit.

More and more men came into view as they trudged up to the ramparts, some of them simply lounging at ease, a group round a fire apparently cooking bacon, others throwing spears at a mark. They looked very much like Englishmen in their grubby woolens, Shef decided. But there was a difference. Every group of men Shef had ever seen before had had in it its proportion of casualties, men not fit to stand in the line of battle: men whose legs had broken and had been set awry; men undersized, deformed; men with bleared eyes from the marsh fever or with old head injuries that affected the way they talked. There were none like that here. Not all were of great stature, Shef was rather surprised to see, but all looked competent, hard-bitten, ready. Some adolescents, but no boys. Bald men and grizzled men, but no palsied elders.

Horses, too. The plain was covered with horses, all hobbled, all grazing. It must take a lot of horses for this army, Shef thought, and a lot of grazing for those horses. In a way that might be a weak point. Shef realized that he was thinking as an enemy, an enemy scouting for opportunities. He was not a king or a thane, but he knew from experience that there was no way to guard all those herds at night, whatever you did. A few true marshmen could reach them however many patrols you had out, could cut them loose and frighten them off. Maybe ambush the horse-guards in the night as well. Then how would the Vikings feel about going on guard duty—if the guards made a habit of never coming back?

Shef felt his spirits sink again as they came up to the entrance. There was no gate, and that was ominous in itself. The track led straight up to a gap in the rampart ten yards broad. It was as if the Vikings were saying, “Our walls protect our goods and keep in our slaves. But we don't need them to hide behind. If you want to fight, march up to us. See if you can get past our gate-guards. It is not these logs that protect us, but the axes that felled them.”

Forty or fifty men stood or sprawled by the gap. They had an air of permanence. Unlike those outside, they all wore mail or leather. Spears were propped against each other in clumps, and shields were in easy reach. These men would be ready for battle within seconds—wherever an enemy might erupt from. They had been scanning Shef, Hund, Thorvin, and party—eight men all told—for minutes as they came into sight. Would they be challenged?

At the gate itself a big man in mail strolled forward and stared at them thoughtfully, making it clear he had noted the two newcomers and everything about them. After a few moments he nodded and jerked a thumb towards the inside. As they passed into the camp itself he called a few words after them. “What does he say?” hissed Shef.

“He says, ‘On your own head be it.’ Something like that.” They walked on into the camp.

Inside, all appeared to be confusion; yet it was a confusion with an underlying regularity, a sense of overriding purpose. Men were everywhere—cooking, talking, playing at knucklebones or squatting over game boards. Canvas tents stretched in all directions, their guy-ropes an inextricable tangle. Yet the path in front of them was never obscured or encroached on. It stretched straight forward, ten paces broad, even its puddles neatly filled with loads or gravel, and the signs of passing carts barely visible on the beaten earth. These men work hard, Shef thought again.

The little group pressed forward. After a hundred yards, when by Shef's calculation they must have been almost in the middle of the camp, Thorvin stopped and beckoned the other two up close.

“I whisper, for there is great danger. Many in this camp speak many languages. We are going to cross the main track that runs north to south. To the right, to the south, down by the river with the ships, is the encampment of the Ragnarssons themselves and their personal followers. No wise man willingly goes there. We shall cross the track and go straight on to my forge near the gate opposite. We will walk straight forward, not even looking down to our right. When we reach the place we will go right into it. Now move. And take heart. Not far now.”

Shef kept his eyes rigidly down as they crossed the broad track, but he wished he could have ventured a moment's gaze. He had come here because of Godive—but where would she be? Did he dare ask for Sigvarth Jarl?

Slowly they moved through the crowds again, till they could see the east stockade almost in front of them. There, a little separated from the others, stood a roughly constructed shelter, open to the side facing them, inside it the familiar apparatus of the smithy: anvil, clay hearth, pipes and bellows. Round it all ran the threads, with the vivid scarlet splashes of quickbeam berries dangling from them. “We are here,” said Thorvin, turning with a sigh of relief. As he turned his eyes passed beyond Shef and the color drained suddenly from his face.

Shef turned with a sense of doom already on him. In front of him there stood a man, a tall man. Shef realized he was looking up at him—realized too how rarely he had done that in the last few months. But this was a man strange for reasons well beyond size.

He was wearing the same wide homespun breeches as everyone else, but no shirt or overtunic. Instead his upper body was wrapped in something like a wide blanket, of a plaid colored a startling yellow. It was pinned over his left shoulder, leaving his right arm bare. Projecting above his left shoulder was the handle of an enormous sword, so great it would have trailed along the ground if slung from a belt. In his left hand he carried a small round buckler with a central grip. An iron spike a foot long stuck out from the center of it. Behind him crowded a dozen others

in the same garb. “Who are these?” he snarled. “Who let they in?” The words were strangely accented but Shef could understand him.

“The gate-wards let them in,” Thorvin replied. “They will do no harm.”

“These two. They are English. Enzkir.”

“The camp is full of English.”

“Aye. Wi' chains round their necks. Give them to me. I'll see they fettered.”

Thorvin paced forward, between Shef and Hund. His five friends spread out, facing the dozen half-naked men in yellow plaids. He gripped Shef's shoulder.

“I have taken this one into the forge, to be my learning-knave.”

The grim face, long-mustached, sneered. “A bonny weight. Maybe ye have other uses for him. The other?” He jerked a thumb at Hund.

“He goes to Ingulf.”

“He's no' there yet. He's had a collar on his neck. Give him to me. I'll see he does no spying.”

Shef felt himself taking a slow pace forward, stomach contracting with fear. He knew resistance was hopeless. There were a dozen of them, all fully armed. In a moment one of those mighty swords would be hacking the limbs from his body or the head from his neck. Yet he could not let his friend be taken. His hand crept to the hilt of his short sword.

The tall men leapt back, hand reaching over shoulder. Before Shef could draw, the longsword had wheeped free. All round, weapons flashed, men sprang on guard.

“Hold,” cried a voice. An immense voice.

While Thorvin and the plaid-wearer had been talking, their group had become the focus of total attention for yards around. Sixty or eighty men now stood in a ring, watching and listening. From the ring now stepped the biggest man Shef had ever seen, taller than Shef by head and shoulders, taller than the man in the plaid, and broader, heavier by far.

“Thorvin,” he said. “Muirtach,” nodding to the strangely dressed one. “What's the stir?”

“I'm taking that thrall there.”

“No.” Thorvin seized Hund suddenly and pushed him through the gap in the enclosure, clenching his hand round the berries. “He is under the protection of Thor.”

Muirtach strode forward, sword raised.

“Hold.” The immense voice again, threatening this time. “You have no right, Muirtach.”

“What's it to you?”

Slowly, reluctantly, the immense man reached inside his tunic, fumbled, brought out a silver emblem on a chain. A hammer.

Muirtach cursed, swept his sword back, spat on the ground “Take him then. But you, boy—” His eye turned to Shef. “You touched yer hilt to me. I catch you on yer own before long. Then ye're dead, boy.” He nodded to Thorvin. “And Thor is nothing to me. No more than Christ and his hoor of a mother. Ye'll not fool me like ye've done him.” He jerked a thumb at the immense man, turned, and walked away down the track, head high, swaggering like one who has met a defeat and will not show it, his fellows straggling after.

Shef realized he had been holding his breath and let it out with careful and affected ease.

“Who are those?” he asked, looking at the retreating men.

Thorvin replied not in English, but in the Norse they had been using, speaking slowly, with stress on the many words the languages had in common. “They are the Gaddgedlar. Christian Irishmen who have left their god and their people and turned Viking. Ivar Ragnarsson has many in his following and hopes to use them to become king of England and Ireland as well. Before he and his brother Sigurth turn their minds back to their own country, to Denmark, and Norway beyond.”

“And there may they never come,” added the immense man who had saved them. He bobbed his head to Thorvin with odd respect, even deference, looked Shef up and down. “That was bold, young swain. But you have irked a mighty man. I too. But for me it has been long in the coming. If you need me again, Thorvin, call. You know that since I took the news to the Braethraborg the Ragnarssons have kept me with them. How long that will last now that I have shown my hammer, I do not know. But in any case I am growing tired of Ivar's hounds.”

He strolled away.

“Who was that?” asked Shef.

“A great champion, from Halogaland in Norway. He is called Viga-Brand. Brand the Killer.”

“And he is a friend of yours?”

“A friend of the Way. A friend of Thor. And so of smiths.”

I do not know what I have got into, thought Shef to himself. But I must not forget why I am here. Unwillingly his eyes drifted away from the enclosure where Hund still stood, toward the danger-center, the southern river-wall of the Viking base, the encampment of the Ragnarssons. She must be there, he thought suddenly. Godive.

Chapter Six

For many days Shef had no time to think of his quest for Godive—or anything else for that matter. The work was too hard. Thorvin rose at dawn and worked on sometimes into the night, hammering, reforging, filing, tempering. In an army of this size there seemed to be innumerable men whose axe-heads had come loose, whose shields needed a rivet, who had decided that their spears needed reshafting. Sometimes there would be a line of men twenty-long, stretched from the forge to the edge of the precinct and on down the lane that led to it. There were also harder and more complex jobs. Several times men brought in mail shirts, torn and bloody, asking for them to be repaired, let out, altered for a new owner. One at a time each link of the mail had to be laboriously fitted into four others, and each of the four others into four others. “Mail is easy to wear, and it gives freedom to the arms,” Thorvin had remarked when Shef finally ventured to grumble. “But it does not give protection against a fierce stroke—and it is hell on earth for smiths.”

As time went by Thorvin handed over the routine jobs more and more to Shef, and concentrated on the difficult or special items. Yet he was rarely far away. He talked continually in Norse, repeating himself as often as was necessary. Sometimes, in the beginning, using mime until he was sure Shef understood. He spoke English well enough, Shef knew, but he would never use it. He insisted too that his apprentice spoke back to him in Norse, even if all he did was repeat what had been said to him. In fact the languages were close to each other in vocabulary and in basic style. After a while Shef caught the trick of repronunciation, and began to think of Norse as a bizarre and aberrant dialect of English, which had only to be imitated, not really learned from the beginning. After that matters went well.

Thorvin's conversation was also a good cure for boredom or frustration. From him, and from the men who stood waiting their turn, Shef learned a great many things that he had never heard before. The Vikings all seemed enormously well-informed about everything that had been decided or intended by their leaders, and had no scruples about discussing it or criticizing it. One thing that soon became clear was that the Great Army of the pagans, feared throughout Christendom, was by no means a unit. At its heart were the Ragnarssons and their followers, maybe half the total. But to these were attached any number of separate contingents, joined to share the loot, of any size from the twenty ships brought down by the Orkney jarl to single crews from villages in Jutland or Skaane. Many of these were already dissatisfied. The campaign had started well enough, they said, with the descent on East Anglia and the establishment of the fortress as a base. Yet the idea had always been not to stay too long, but to gather horses, acquire guides, and then move suddenly from a firm base in the East Anglian kingdom against the true enemy and target, the kingdom of Northumbria.

“Why not land with the ships in Northumbria in the first place?” Shef had asked once, wiping the sweat from his forehead and signaling to the next customer.

The stocky, balding Viking with the dented helmet had laughed, loudly but without malice. The really tricky part of a campaign, he had said, was always getting started. Getting the ships up the river. Finding a place to beach them. Getting horses for thousands of men. Contingents turning up late and going down the wrong river. “If the Christians had the sense they were born with,” he had said emphatically, spitting on the ground, “they would

pick us off before we got started almost every time.”

“Not with the Snakeeye in charge,” another man had remarked.

“Maybe not,” the first Viking had agreed. “Maybe not with the Snakeeye. But lesser commanders. Do you remember Ulfketil down in Frankland?”

So, better to get your feet planted before you tried to hit, they had agreed. Good idea. But this time it had gone wrong. Their feet were planted too long. It was that there King Edmund, most of the customers agreed—or “Jatmund” as they pronounced it—and the only question was, what was making him act so stupid? Easy to ravage his country till he gave in. But they didn't want to ravage East Anglia, the customers complained. Takes too long. Too thin pickings. Why in Hell didn't the king just pay up and come to a sensible deal? He'd had a warning.

Maybe too much of a warning, Shef thought, remembering the wasted face of Wulfgar in the horse-trough, and that indefinable buzz of rage which he had felt in the fields and woods on their journey. When he asked why the Vikings were so determined to march on Northumbria, largest but not by any means richest of the English kingdoms, the laughter at that question took a long time to die down. Eventually, when he unraveled the tale of Ragnar Lothbrok and King Ella, of the old boar and the little pigs who would grunt, of Viga-Brand and his taunting of the Ragnarssons themselves in the Braethraborg, a chill fell on him. He remembered the strange words he had heard from the blue-swelling face in the snake-pit of the archbishop, the sense of foreboding he had known at the time.

Now he understood the need for revenge—but there were other things about which he remained curious.

“Why do you say ‘Hell’?” he asked Thorvin one night after they had put their gear away and were sitting mulling a tankard of ale on the cooling forge. “Do you believe there is a place where sins are punished after death? Christians believe in Hell—but you're no Christian.”

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

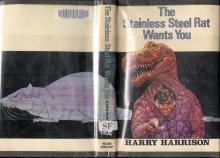

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

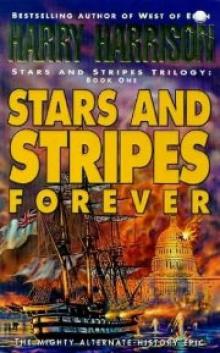

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

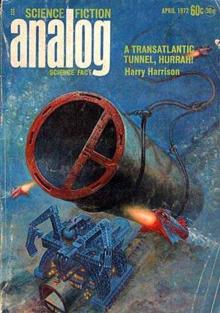

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

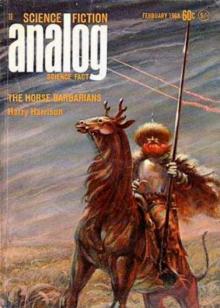

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

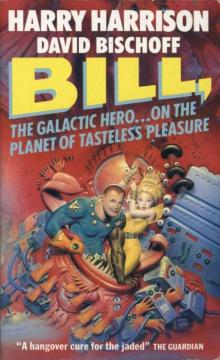

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures