- Home

- Harry Harrison

The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine Read online

The Technicolor Time Machine

Harry Harrison

Why pay for costumes, scenery, props or actors when the most brilliant drama of all time is unfolding before your very eyes, in vivid color—in 1050 A.D.? Just the film crew of that stupendous motion picture saga Viking Columbus as they journey back in time to capture history in the making.

First published as The Time-Machined Saga.

Harry Harrison

The Technicolor Time Machine

1

“What am I doing here? How did I let myself be talked into this?” L.M. Greenspan groaned as dinner scraped at his ulcer.

“You are here, L.M., because you are a far-sighted, quick-thinking executive. Or to put it another way, you have to grasp at any straw handy, because if you don’t do something fast Climactic Studios will sink without a trace.” Barney Hendrickson puffed spasmodically at the cigarette he clutched between yellowed fingers and stared unseeingly at the canyon landscape that rushed soundlessly past the window of the Rolls-Royce. “Or to put it even another way, you are investing one hour of your time in the examination of a project that may mean Climactic’s salvation.”

L.M. gave all of his attention to the delicate project of lighting a smuggled Havana cigar: clipping the end with his gold pocket clipper, licking the truncated tip, waving the wooden match about until all the chemicals had burned away, then gently puffing the slender greenish form to life. The car slid over to the curb with the ponderous ease of a hydraulic ram and the chauffeur rushed around to open the door. L.M. stared out suspiciously without moving.

“A dump. What could there be in a dump like that that could possibly save the studio?”

Barney pushed unsuccessfully at the unmoving and solid form. “Don’t prejudge, L.M. After all, who could have predicted that a poor kid from the East Side slums would one day be head of the largest film company in the world?”

“Are you getting personal?”

“Let’s not get sidetracked,” Barney insisted. “Let’s first go inside and see what Hewett has to offer and make our preconceptions afterwards.”

Reluctantly, L.M. allowed himself to be urged up the cracked flagstone walk to the front door of the run-down stucco house and Barney held him firmly by the arm while he rang the bell. He had to ring twice more before the door rattled open and a small man with a large bald head and thick-rimmed glasses peered out at them.

“Professor Hewett,” Barney said, pushing L.M. forward, “This is the man I talked to you about, none other than the head of Climactic Studios himself, Mr. L.M. Greenspan.”

“Yes, of course, come in…” The professor blinked fishily behind his round glasses and stood aside so they could enter.

Once the door was closed behind his back L.M. sighed and surrendered, allowing himself to be led down a flight of squeaking stairs into the basement. He halted abruptly when he caught sight of the banks of electrical equipment, the festooned wires and humming apparatus.

“What is this? It looks like an old set for Frankenstein.”

“Let the professor explain.” Barney urged him forward.

“This is my life work,” Hewett said, waving his hand roughly in the direction of the toilet.

“What kind of life work is that?”

“He means the machines and apparatus, he’s just not pointing very well.”

Professor Hewett did not hear them. He was busy making adjustments at a control board. A thin whining rose in pitch and sparks began to fall from a hulking mass of machinery.

“There!” he said, pointing dramatically—and with considerably more accuracy this time—at a metal platform set on thick insulators, “That is the heart of the vremeatron, where the displacement takes place. I will not attempt to explain the mathematics to you, you could not possibly understand them, or go into the complex details of the machine’s construction. I feel that a demonstration of the vremeatron in operation will be wisest at this point.” He bent and groped under a table and brought out a dusty beer bottle that he put on the metal platform.

“What is a vremeatron?” L.M. asked suspiciously.

“This is. I shall now demonstrate. I have placed a simple object in the field which I shall now activate. Watch closely.”

Hewett threw a switch and electricity arced from the transformer in the comer, the mechanical howl turned to a scream while banks of tubes flashed brilliantly and the air filled with the smell of ozone.

The beer bottle flickered briefly and the roar of the apparatus died away.

“Did you see the displacement? Dramatic wasn’t it?” The professor glowed with self-appreciation and pulled a length of paper marked with squiggles of ink out of a recording machine. “Here it is, on the record. That bottle traveled back seven microseconds in time then returned to the present. In spite of what my enemies say the machine is a success. My vremeatron—from vreme, the Serbo-Croatian for ‘time,’ in honor of my maternal grandmother, who was from Mali Lošinj—is a workable time machine.”

L.M. sighed and turned to the stairs. “A nut,” he said.

“Hear him out, L.M., the professor has some ideas. It is only because he has been turned down by all the foundations in his requests for funds that he will even consider working with us. All he needs is some finance to jazz his machine up.”

“There’s one born every minute. Let’s go.”

“Just listen to him,” Barney pleaded. “Let him show you the one where he sends the beer bottle into the future. This is too impressive to ignore.”

“There is a temporal barrier in any motion towards the future, I must explain that carefully. Displacement toward the future requires infinitely more energy than displacement into the past. However, the effect still operates—if you will watch the bottle closely.”

Once again the miracle of electronic technology clashed with the forces of time and the air crackled with the discharge. The beer bottle flickered, ever so slightly.

“So long.” L.M. started up the stairs. “And P.S., Barney, you’re fired.”

“You can’t leave yet—you haven’t given Hewett a chance to prove his point, or even to let me explain.” Barney was angry, angry at himself, at the dying company that employed him, at the blindness of man, at the futility of man, at the fact he was overdrawn in the bank. He raced up behind L.M. and whipped the smoking Havana from his chops. “We’ll have a real demonstration, something you can appreciate!”

“They cost two bucks apiece! Give it back—”

“You’ll have it back, but watch this first.” He hurled the beer bottle to the floor and put the cigar on the platform. “Which one of these gadgets is the power control?” he asked Hewett.

“This rheostat controls the input, but why? You cannot raise the temporal displacement level without burning out the equipment—stop!”

“You can buy new equipment, but if you don’t convince L.M., you’re on the rocks and you know it. Shoot for the moon!”

Barney held the protesting professor off with one hand while he spun the power to full on and slammed the operation switch shut. This time the results were far more spectacular. The scream rose to a banshee wail that hurt their ears, the tubes glowed with all the fires of hell, brighter and brighter, while static charges played over the metal frames; their hair stood straight up from their heads and gave off sparks.

“I’m electrocuted!” L.M. shouted as, with a last burst of energy, all the tubes glared and exploded and the lights went out.

“There—look there!” Barney shouted as he thumbed his Ronson to life and held the flame out. The metal platform was empty.

“You owe me two bucks.”

“Look, gone! Two seconds at least, three… four… five…

six…”

The cigar suddenly reappeared on the platform, still smoking, and L.M. grabbed it up and took a deep drag.

“All right, so it’s a time machine, so I believe you. But what has this got to do with making films or keeping Climactic off the rocks?”

“Let me explain…”

2

There were six men in the office, grouped in a semicircle in front of L.M.’s desk.

“Lock the door and cut the phone wires,” he ordered.

“It’s three in the morning,” Barney protested. “We can’t be overheard.”

“If the banks get wind of this I am ruined for life, and maybe longer. Cut the wires.”

“Let me take care of it,” Amory Blestead said, standing and taking an insulated screwdriver from his breast pocket—he was the head of Climactic Studios’ technical department. “The mystery is at last solved. For a year now my boys have been repairing these cut wires on the average of twice a week.” He worked quickly, taking the tops off the junction boxes and disconnecting the seven telephones, the intercom, the closed circuit television and the Muzak wire. L.M. Greenspan watched him closely and did not talk again until he had personally seen all ten wires dangling freely.

“Report,” he said, stabbing his finger at Barney Hendrickson.

“Things are ready to roll at last, L.M. All of the essential machinery for the vremeatron has been built on the set for The Creature’s Son Marries the Thing’s Daughter and the expenses have been covered by the budget for this picture. In fact there was a bit of a saving there, the professor’s machines cost less than the usual props—”

“Don’t digress!”

“Right. Well, the last laboratory scenes for the monster picture were shot this afternoon, yesterday afternoon I mean, so we got some grips in later on overtime and cleaned all the machinery out. As soon as they were gone the rest of us here mounted it in the back of an army truck from the set of The Pfc. from Brooklyn and the Prof has hooked it up and tested everything. It’s ready to go.”

“I don’t like the truck—it’ll be missed.”

“No, it won’t, L.M., everything has been taken care of. It was government surplus in the first place and was going to be disposed of in the second. It was sold legally through our usual outlet and bought by Tex here, I told you—we’re in the clear.”

“Tex, Tex—who is he? Who are all these people?” L.M. complained, darting suspicious glances around the circle. “I thought I told you to keep this thing small, hold it down until we saw how it works, if the banks get wind…”

“This operation is as small as it could possibly be. There is myself and the Prof, whom you know, and Blestead, who is your own technical chief and has been with you for thirty years—”

“I know, I know—but what about those three?” He waved a finger at two dark and silent men dressed in Levis and leather jackets, and at a tall, nervous man with reddish blond hair. Barney introduced them.

“The two in the front are Tex Antonelli and Dallas Levy, they’re stunt men…”

“Stunt men! What kind of a stunt you pulling bringing in two phony cowboys?”

“Will you kindly relax, L.M. We need help on this project, trustworthy men who can keep quiet and who know their way around in case of any trouble. Dallas was in the combat infantry, then on the rodeo circuit before lie came here. Tex was thirteen years in the Marines and an instructor in unarmed combat.”

“And the other guy?”

“That’s Dr. Jens Lyn from U.C.L.A., a philologist.” The tall man rose nervously and made a quick bow toward the desk. “He specializes in German languages or something like that, and is going to do our translating for us.”

“Do you all realize the importance of this project now that you are members of the team?” L.M. asked.

“I’m getting paid my salary,” Tex said, “and I keep my mouth shut.” Dallas nodded in silent agreement.

“This is a wonderful opportunity,” Lyn said rapidly, with a slight Danish accent. “I have taken my sabbatical, I would even accompany you even without the generous honorarium as a technical adviser, we know so little of spoken Old Norse—”

“All right, all right,” L.M. lifted his hand, satisfied for the moment. “Now what is the plan? Fill me in on the details.”

“We have to make a trial run,” Barney said. “See if the Profs gadget really does work—”

“I assure you… !”

“And if it does work we set up a team, work out a script, then go out and shoot it on location. And what a location! All of history is open to us on wide screen! We can film it all, record it—”

“And save this studio from bankruptcy. No salary for extras, no sets to be built, no trouble with the unions…”

“Watch it!” Dallas said, scowling.

“Not your union, of course,” L.M. apologized. “All of the crew from here will be employed at scale and above, with bonuses, I was just thinking of the savings at the other end. Go now, Barney, while I am still enthusiastic, and do not come back until you have good news for me.”

They footsteps echoed from the cement path between the giant sound stages and their shadows stretched first in back, then in front of them as they walked through the pools of light under the widely spaced lamps. In the stillness and loneliness of the deserted studios they had sudden thoughts about the magnitude of what they were attempting and they moved, unconsciously, closer together as they walked. There was a studio guard outside the building who saluted as they approached and his voice broke the morbid spell.

“Tight as a drum, sir, and no disturbances at all.”

“Fine,” Barney told him. “We’ll probably be here the rest of the night, classified work, so see that no one gets near this area.”

“I’ve already told the captain and he’s passed the word to the boys.”

Barney locked the door behind them and the lights flared from the rafters above. The warehouse was almost empty, except for a few dusty flats leaning against the back wall and an olive-drab truck with the white army star on its door and canvas turtleback.

“The batteries and accumulators are charged,” Professor Hewett announced, clambering into the back of the truck and tapping on a number of dials. He unhooked the heavy cables that ran to the junction box in the wall and handed them out. “You may board, gentlemen, the experiment can begin any time now.”

“Would you call it something else besides experiment?” Amory Blestead asked nervously, suddenly beginning to regret his involvement.

“I’m getting into the cab,” Tex Antonelli said. “I’ll feel more comfortable there. I drove a six-by like this all through the Marianas.”

One by one they followed the professor into the rear of the truck and Dallas locked up the tailgate. The banks of electronic machinery and the gasoline-powered motor-generator filled most of the space and they had to sit on the boxes of equipment and supplies.

“I am ready,” the professor announced. “Perhaps for the first trial we might take a look in on the year 1500 A.D.?”

“No.” Barney was firm. “Set 1000 A.D. on your dials just as we decided and pull the switch.”

“But the power expenditure would be less, the risk even…”

“Don’t chicken out now, Professor. We want to get as far back as possible so that no one will be able to recognize the machinery as machinery and cause us any trouble. Plus the fact that the decision has been made to do a Viking picture, not a remake of The Hunchback of Notre Dame.”

“That would be in the sixteenth century,” Jens Lyn said. “I would date the setting in medieval Paris rather earlier, about…”

“Geronimo!” Dallas growled. “If we’re gonna go let’s stop jawing and go. It spoils the troops if you horse around and waste time before going into combat.”

“That is true, Mr. Levy,” the professor said, his fingers moving over the controls. “1000 anno domini it is—and here we go!” He cursed and rumbled at the controls. “So many of the switches a

nd dials are dummies that I get confused,” he complained.

“We had to make the machines so they could be used in the horror film,” Blestead said, talking too fast. There was a fine beading of sweat on his face. “The machines had to look realistic.”

“So you make them unrealistic, bah!” Professor Hewett muttered angrily as he made some final adjustments and threw home a large multipoled switch.

The throbbing of the motor-generator changed as the sudden load came on, and a crackling discharge filled the air above the apparatus: sparks of cold fire played over all the exposed surfaces and they felt the hair on their heads rising straight up.

“Something’s gone wrong!” Jens Lyn gasped.

“By no means,” Professor Hewett said calmly, making a delicate adjustment. “Just a secondary phenomenon, a static discharge of no importance. The field is building up now, I think you can feel it.”

They could feel something, a distinctly unpleasant sensation that gripped their bodies solidly, a growing awareness of tension.

“I feel like somebody stuck a big key in my belly button and was winding up my guts,” Dallas said.

“I would not phrase it in exactly that manner,” Lyn agreed, “but I share the symptoms.”

“Locked on to automatic,” the professor said pushing home a button and stepping away from the controls. “At the microsecond of maximum power the selenium rectifiers will trip automatically. You can monitor it here, on this dial. When it reaches zero…”

“Twelve,” Barney said, peering at the instrument, then turning away.

“Nine,” the professor read. “The charge is building up. Eight… seven… six…”

“Do we get combat pay for this?” Dallas asked, but no one as much as smiled.

“Five… four… three…”

The tension was physical, part of the machine, part of them. No one could move. They stared at the advancing red hand and the professor said:

“Two… one…”

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

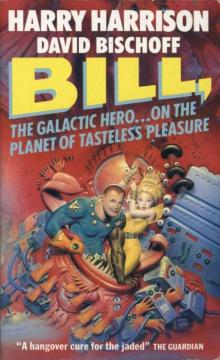

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures