- Home

- Harry Harrison

Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams Read online

Harry Harrison is one of the best known science fiction writers in the world. For forty years he has written SF ranging from the slambang adventure of Deathworld to the humour of The Stainless Steel Rat; from the sweeping grandeur of the Eden novels to the bleak, overcrowded future of Make Room! Make Room! Not to mention Bill, The Galactic Hero. There is no area of science fiction to which Harrison has not applied his outstanding writing skills and considerable energy.

Many of Harrison’s finest short stories are collected here in Galactic Dreams, an Illustrated companion volume to the acclaimed Stainless Steel Visions (also published by Legend). And as a bonus, there is a brand new Bill, the Galactic Hero story. Galactic Dreams is a tribute to Harrison’s continued mastery of the art of science fiction writing over forty Years.

Harry Harrison was born in Stamford Connecticut He served in the United States Army Corps in World War 2 and became a freelance commercial artist in 1946. Since the early fifties he has written many bestselling books including the Stainless Steel Rat, the Eden trilogy. Make Room! Make Room! (filmed as Soylent Green) and the Deathworld novels. The Hammer and The Cross`, Harrison’s excursion into an alternative Ninth Century Britain, has been published recently by Legend. Harry Harrison lives with his wife, Jean, in Ireland.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Forthcoming in Legend Books

The Hammer and the Cross

GALACTIC DREAMS by Harry Harrison

Illustrated by Bryn Barnard

Copyright © 1994 Harry Harrison This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious, and any resemblance to real people or events is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved The right of Harry Harrison to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 Legend Books Random House Group 20 Vauxhall Bridge Rd, London SWIV 2SA Random House South Africa (Pty) Ltd PO Box 337, Bergvlei 2012, South Africa Random House Australia Pty Ltd 20 Alfred Street, Milsons Point, Sydney, NSW 2061 Australia Random House New Zealand Ltd PO Box 40-086, Glenfield, Auckland 10 New Zealand The catalogue data record for this book is available from the British Library Typeset by Deltatype Ltd, Ellesmere Port, Cheshire Printed in England by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Contents:

1, I ALWAYS DO WHAT TEDDY SAYS

2, SPACE RATS OF THE CCC

3, DOWN TO EARTH

4, A CRIMINAL ACT

5, FAMOUS FIRST WORDS

6, THE PAD - A STORY OF THE DAY AFTER THE DAY AFTER TOMORROW

7, IF

8, MUTE MILTON

9, SIMULATED TRAINER

10, AT LAST, THE TRUE STORY OF FRANKENSTEIN

11, THE ROBOT WHO WANTED TO KNOW

12, BILL THE GALACTIC HERO'S HAPPY HOLIDAY

1:

I ALWAYS DO WHAT TEDDY SAYS

The little boy lay sleeping. The moonlight effect of the picture-picture window threw a pale glow across his untroubled features. He had one arm clutched around his teddy bear, pulling the round face with its staring button eyes close to his own. His father, and the tall man with the black beard, tiptoed silently across the nursery to the side of the bed.

“Slip it away,” the tall man said. “Then substitute the other.

“No, he would wake up and cry,” Davy’s father said. “Let me take care of this. I know what to do.

With gentle hands he laid the second teddy bear down next to the boy, on the other side of his head. His sleeping cherub face was framed by the wide-eared unsleeping masks of the toys. Then he carefully lifted the boy’s arm from the original teddy and pulled it free. This disturbed Davy without waking him. He ground his teeth together and rolled over, clutching the substitute toy to his cheek. Within a few moments his soft breathing was regular and deep again. The boy’s father raised his forefinger to his lips and the other man nodded; they left the room without making a sound, closing the door noiselessly behind them.

“Now we begin,” Torrence said, reaching out to take the teddy bear. His lips were small and glistened redly in the midst of his dark beard. The teddy bear twisted in his grip and the black-button eyes rolled back and forth.

“Take me back to Davy,” it said in a thin and tiny voice.

“Let me have the thing back,” the boy’s father said. “It knows me and won’t complain.

His name was Numen and, like Torrence, he was a Doctor of Government. Despite their outstanding abilities both DGs had been made redundant, were unemployed by the present government.

They had no physical resemblance. Torrence was a bear, though a small one, a black bear with hair sprouting thickly on his knuckles, twisting out of his white cuffs and lining his ears. His beard was full and thick rising high up on his cheekbones and dropping low on his chest.

Where Torrence was dark Numen was fair, where short he was tall, thick, thin. A thin bow of a man, bent forward with a scholar’s stoop and, though balding now, his hair was still curled and blond and very much like the golden ringlets of the boy asleep upstairs. Now he took the toy animal and led the way to the shielded room deep in the house where Eigg was waiting.

“Give it here-here! Eigg snapped when they came in, reaching for the toy. Eigg was always like that, in a hurry, surly, square and solid with his width of jaw and spotless white laboratory smock. But they needed him.

“Gently,” Numen said, but Eigg had already pulled it from his grasp. “It won’t like it, I know …

“Let me go … let me go… ! the teddy bear said with a hopeless shrill.

“It is just a machine,” Eigg said coldly, putting in face down on the table and reaching for a scalpel. “You are a grown man, you should be more logical, have your emotions under greater control. You are speaking with your childhood memories, seeing your own boyhood teddy who was your friend and companion. This is only a machine.

With a quick slash he opened the fabric over the seam seal and touched it: the plastic-fur back gaped open like a mouth.

“Let me go … let me go … the teddy bear wailed while its stumpy arms and legs waved back and forth. Both of the onlookers went white.

“Must we… ?

“Emotions. Control them,” Eigg said and probed with a screwdriver. There was a click and the toy went limp. He began to unscrew a plate in the mechanism.

Numen turned away and found that he had to touch a handkerchief to his face. Eigg was right. He was being emotional. This was just a machine. It was singularly stupid of him to get emotional over it. Particularly with what they had in mind.

“How long will it take?

He looked at his watch; it was a little past 2100.

“We have been over this before and discussing it again will not change any of the factors.

Eigg’s voice was distant as he removed the tiny plate and began to examine the machine’s interior with a magnifying probe. “I have experimented on the two stolen teddy tapes, carefully timing myself at every step. I do not count removal or restoration of the tape, that is just a few minutes for each. The tracking and altering of the tape in both instances took me under ten hours. My best time differed from my worst time by less than fifteen minutes, which is not significant. We can therefore safely say - ahh. He was silent for a moment while he removed the capsule of the memory spools. “… We can safely say that this is a ten-hour operation.

“That is too long. The boy is usually awake by seven, we must have the teddy back by then. He must never suspect that it has been away.

“There is little risk, you can give him some excuse for the time. I will not rush and spoil the work. Now be silent.

The two government specialists could only sit back and watch while Eigg inserted the capsule into the bulky machine that he h

ad assembled in the room. This was not their speciality.

“Let me go … the tiny voice said from the wall speaker, then was interrupted by a burst of static. “Let me go … bzzzzzzt … no, no Davy, Mummy wouldn’t like you to do that … fork in left, knife in right … if you do you’ll have to wipe … good boy good boy good boy …

The voice squeaked and whispered and went on and on, while the hours on the clock went by, one by one. Numen brought in coffee more than once. Towards dawn Torrence fell asleep up in the chair, only to awake with a guilty start. Of them all Eigg showed no strain or fatigue, working the controls with fingers regular as a metronome. The reedy voice from the capsule shrilled thinly through the night like the memory of a ghost.

“It is done,” Eigg said, sealing the fabric with quick surgeon’s stitches.

“Your fastest time ever,” Numen sighed with relief. He glared at the nursery viewscreen that showed his son sleeping soundly, starkly clear in the harsh infrared light. “And the boy is still asleep. There will be no problem getting the teddy back to him after all. But is the tape… ?

“It is right, perfect, you heard that. You asked the questions and heard the answers. I have concealed all traces of my work. Unless you know what to look for in the alterations you would never find the changes. In every other way the memory and instructions are like all the others. There has just been this single change made.

“Pray God we never have to use it,” Numen said.

“I did not know that you were religious,” Eigg said, turning to look at him, his face expressionless. The magnifying loupe was still in his eye and it stared coldly at him. Five times the size of its fellow, a large and probing questioner.

“I’m not,” Numen said, flushing.

“We must get the teddy back,” Torrence broke in. “The boy just moved.

Davy was a good boy and, when he grew older, a good student in school. Even after he began classes he kept teddy around and talked to him while he did his homework.

“How much is seven and five, teddy?

The furry toy bear rolled its eyes and clapped stubby paws. “Davy knows … shouldn’t ask teddy what Davy knows …

“Sure I know - I just wanted to see if you did. The answer is thirteen.

“Davy … the answer is twelve … you better study harder Davy … that’s what teddy says …

“Fooled you! Davy laughed. “Made you tell me the answer!

He was finding ways to get around the robot controls, permanently fixed to answer the question of a younger child. Teddies have the vocabulary and outlook of the very young because their job must be done during the formative years. Teddies teach diction and life history and morals and group adjustment and vocabulary and grammar and all the other things that enable men to live together as social animals. A teddy’s job is done early in the most plastic stages of a child’s life. By the very nature of its task its conversation must be simple and limited. But effective. By the time teddies are discarded as childish toys their job is done.

By the time Davy became David and was eighteen years old, teddy had long since been retired behind a row of books on a high shelf. He was an old friend who had outgrown his useful days. But he was still a friend and certainly couldn’t be discarded. Not that David ever thought of it that way. Teddy was just teddy and that was that. The nursery was now a study, his cot a bed and with his birthday past David was packing because he was going away to the university. He was sealing his bag when the phone bleeped and he saw his father’s tiny image on the screen.

“David …

“What is it, Father?

“Would you mind coming down to the library now. There is something rather important.

David squinted at the screen and noticed for the first time that his father’s face had a pinched, sick look. His heart gave a quick jump.

“I’ll be right down!

Dr. Eigg was there, arms crossed and sitting almost at attention. So was Torrence, his father’s oldest friend. Though no relation, David had always called him Uncle Torrence. And his father was obviously ill at ease about something. David came in, quickly conscious of all their eyes upon him as he crossed the room and took a chair. He was a lot like his father, with the same build and height. A relaxed, easy-to-know boy with very few problems in life.

“Is something wrong? he asked.

“Not wrong, Davy,” his father said. He must be upset, David thought, he hasn’t called me that in years. “Or rather something is wrong, but with the state of the world, has been for a long time.

“Oh, the Panstentialists,” David said, and relaxed a little. He had been hearing about the evils of Panstentialism as long as he could remember. It was just politics; he had been thinking something very personal was wrong.

“Yes Davy, I imagine you know all about them by now. When your mother and I separated, I promised to raise you to the best of my ability and I think that I have. But I am a governor and all of my friends work in government so I’m sure you have heard a lot of political talk in this house. You know our feelings and I think you should share them.

“I do - and I think I would have no matter where I grew up. Panstentialism is an oppressing philosophy and one that perpetuates itself in power.

“Exactly. And one man, Barre, is at the heart of it. He stays in the seat of power and will not relinquish it and, with the rejuvenation treatments, will be good for a hundred years more.

“Barre must go!

Eigg snapped. “For twenty-three years now he has ruled - and forbidden the continuation of my experiments. Young man, he has stopped my work for a longer time than you have been alive, do you realize that?

David nodded, but he did not comment. What little he had read about Dr. Eigg’s proposed researches into behavioral human embryology had repelled him: secretly, he was in agreement with Barre’s ban on the work. But on this only. For the rest he was truly in agreement with his father. Panstentialism was a heavy and dusty hand on the world of politics - as well as the world at large.

“I’m not speaking only for myself,” Numen said, his face white and strained. “But for everyone in the world, everyone who is against Barre and his philosophies. I have not held a government position for over twenty years - nor has Torrence here - but I think he’ll agree that this is a small thing. If this were a service to the people we would gladly suffer it. Or if our persecution was the only negative result of Barre’s evil works I would do nothing to stop him.

“I am in complete agreement. Torrence nodded. “The fate of two men is of no importance in comparison to the fate of us all. Nor is the fate of one man.

“Exactly!

Numen sprang to his feet and began to pace agitatedly up and down the room. “If that wasn’t true, wasn’t the heart of the problem, I would never consider being involved. There would be no problem if Barre suffered a heart attack and fell dead tomorrow.

The three older men were all looking at David now, though he didn’t know why, and he felt they were waiting for him to say something.

“Well, yes - I agree. A little coronary embolism right now would be the best thing for the world that I can think of. Barre dead would be of far greater service to mankind than Barre alive has ever been.

The silence lengthened, became embarrassing, and it was finally Eigg who broke it with his dry mechanical tones.

“We are all then in agreement that Barre’s death would be of immense benefit. In that case, David, you must also agree that it would be fine if he could be … killed… .

“Not a bad idea,” David said, wondering where all this talk was going. “Though of course that is a physical impossibility. It must be centuries since the last … what’s the word, `murder’ took place. The developmental psychology work took care of that a long time ago. As the twig is bent and all that sort of thing. Wasn’t that supposed to be the discovery that finally separated man from the lower orders, the proof that we could entertain the thought of killing and discuss it, yet still be trained in

our early childhood so that we would not be capable of the act. Surely, if you can believe the textbooks, the human race has progressed immeasurably since the curse of killing has been removed. Look-do you mind if I ask you what this is all about… ?

“Barre can be killed,” Eigg said in an almost inaudible voice. “There is one man in the world who can kill him.

“Who? David asked and in some terrible way he knew the answer even before the words came from his father’s trembling lips.

“You, David … you…. He sat, unmoving, and his thoughts went back through the years, and a number of things that had been bothering him were now made clear. His attitudes so subtly different from his friends’, and that time with the airship when one of the rotors had killed a squirrel. Little puzzling things - and sometimes worrying ones that had kept him awake long after the rest of the house was asleep. It was true, he knew it without a shadow of a doubt, and wondered why he had never realized it before. But, like a hideous statue buried in the ground beneath one’s feet, it had always been there but had never been visible until he had dug down and reached it. It was visible now with all the earth scraped from its vile face, all the lineaments of evil clearly revealed.

“You want me to kill Barre? he asked.

“You’re the only one who can … Davy … and it must be done. For all these years I have hoped against hope that it would not be needed. That the … ability you have would not be used. But Barre lives. For all our sakes, he must die.

“There is one thing I don’t understand,” David said, rising and looking out the window at the familiar view of the trees and the glass canopied highway. “How was this change made? How could I miss the conditioning that is a normal part of existence in this world?

“It was your teddy bear,” Eigg explained. “It is not publicized, but the reaction to killing is established by the tapes in the machine that every child has. Later education is just reinforcement, valueless without the earlier indoctrination.

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

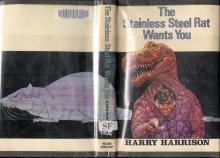

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

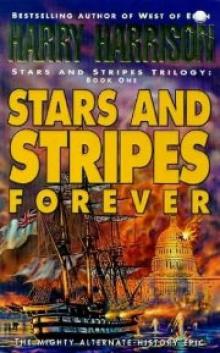

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

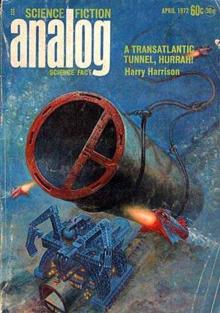

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

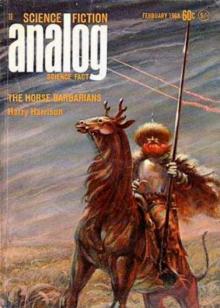

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

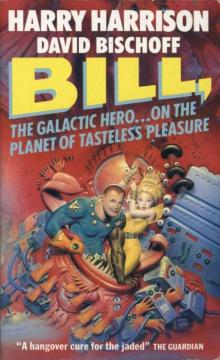

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures