- Home

- Harry Harrison

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Read online

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Harry Harrison

Harry Harrison was born in Stamford, Connecticut in 1925 and lived in New York City until 1943, when he joined the United States Army. He was a machine-gun instructor during the war, but returned to his art studies after leaving the army. A career first as a commercial illustrator and later as art director and editor for various picture, news, and fiction magazines fitted him only for a lifetime residence in New York, so he changed it for the freelance writer's precarious existence and moved his family to Cuautla, Mexico. Since then he has lived in Kent, Camden, Italy, Denmark, Spain and Surrey; he has now returned to his native land, but he has not ceased to wander. He rationalizes this continual change of residence as essential research, when in reality it is an incurable case of wanderlust that enables him to indulge all his enthusiasms: travel, skiing, practising Esperanto, and making an annual pilgrimage to the Easter Congress of the British Science Fiction Association.

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

By

Harry Harrison

1

JEST 89,000 VOLTS

"Come on, Jerry," Chuck called out cheerfully from inside the rude shed that the two chums had fixed up as a simple laboratory. "The old particle accelerator is fired up and rarin' to go!"

"I'm fired up and rarin' to go too," Jerry whispered into the delicate rose ear of lovely Sally Goodfellow, his lips smacking their way along her jaw towards her lips, his insidious hands stealthily encircling her waist.

"Silly!" Sally giggled and wriggled free of his powerful, yet tender embrace with a solid blow of the heel of her hand against his chin. "You know that I like Chuck just as much as I like you." Then, with a saucy toss of her shoulder-length locks she was gone, and Jerry looked after her longingly, fingering his bruised jaw.

"Come on, Jerry, the accumulators are crackling with barely restrained power," Chuck shouted.

"Here I come."

Jerry entered the shed and closed and locked the door carefully behind him, for there were discoveries and yetunpatented inventions here that would set the largest corporations in the land to licking their lips. It just so happened that these two young men, still students at a secluded State College in drowsy Pleasantville, had two of the keenest minds in the country, perhaps the entire world. Tall, dark-haired, broad-shouldered Jerry Courteney, handsome as a Greek god with a whimsical smile forever playing about his lips, would never be taken for the topnotch engineer that he was, the man who walked off with every medal and every award in every field that he chose to study. He looked less like a scholar than the rugged frontiersman he really was, for he had been born up on the far northern border of our country, on a homesteaded ranch in Alaska north of the Arctic Circle. In that rough environment he had grown up with his four strapping brothers and strapping father, who strapped them all quite well when they got out of line, as high-spirited boys ever will. The others were all still there, hewing a precarious living from the virgin wilderness, but much as he loved the icy silences and whispering trees, Jerry had been bitten by the bug of knowledge, just as his arms were bitten by the ravenous mosquitoes so his skin was tougher than shoe leather, and had made his way from school to school, scholarship to scholarship until he reached State College.

Chuck van Chider, no less of a genius, had had a far easier time of it. A blond giant of man with arms as thick as a strong man's legs, he was the heart and spirit of the State Stegasauri, the championship football team, the man who could open a hole in any line, who could carry the ball through any number of grappling foe. When he remembered to. Twice during the last season he had stopped stock still with the game surging around him as a solution to a complicated mathematical problem suddenly presented itself to him. He went on to win these games, so his teammates never minded the blank moments, and he was also the heir to the van Chider millions which also did not make him any enemies. Born with a platinum spoon in his mouth, his father had prospected a platinum mine on the very spot where the Pleasantville Mental Hospital now stood; he had never known want. Before the mine had played out, the shrewd Chester van Chider had sold out and used the money to buy the tiny cheese works outside of town. By the addition of inert ingredients and deliquescing agents to the sturdy cheese he had built a world wide market for Van Chider Cheddar – and a fortune for himself. Though discontented radicals from the lunatic fringe often said his cheese tasted like rancid sealing wax, the public at large loved it, mostly for its deliquescing agents which absorbed water from the atmosphere so that after a few days, if you didn't eat fast enough, you had more cheese than you started with. Chester van Chider was a shrewd businessman, unlike the greedy operators who bought his platinum mine only to have it play out a few weeks later, this blow being so great that most of them ended up in the aforementioned looney bin built on the minesite. The keen business mind of the father was reflected in the mathematical genius of the son.

In some ways as different as night and day, blond and dark-haired, wiry and stocky, the two friends were very much alike inside. They had strong hearts and rugged digestions – and minds that were as keen as any that could be found. All around them, in the cluttered laboratory that had once been a simple shed, lay the fruits of their mutual genius. A tossed-aside bit of breadboard circuitry that would one day revolutionize long-line transmission of electricity, a bit of scribbled paper that elaborated a simple equation for squaring the circle. These were the playthings of their ever-curious minds – and their latest plaything now filled the room and hummed with life. A massive, hulking, 89,000-volt particle accelerator that they had put together from surplus electromagnets and a rusty water boiler. High-density batteries of their own invention brimmed full of electricity, and all that was required now was to throw the great gang switch to send the charged particles smashing into the target. "Put the rubidium on the target area, will you?" Chuck called out, busily at work adjusting a meter, his thick, strong fingers as delicate as those of a master watchmaker at the precise job.

"Right on," Jerry answered and reached for the sample of the rare metal they were bombarding – but seized instead a piece of Van Chider Cheddar from the large wheel they always kept nearby. It was a moment of youthful madness, a harmless jest brought on perhaps by the stillwarm memory of those precious lips against which his had so recently rested. Filled with the joy of life, he prized the damp piece of cheese free and slapped it onto the chamber and sealed and evacuated it.

"Stand clear," Chuck shouted. "There she blows!" With a mighty crackling the batteries discharged completely, and the sharp smell of ozone filled the air. Visible only as a sudden fine beam of purple Ught, the particles struck the target and vanished.

"Experiment eighty-three," Chuck said, licking a pencil and making a note on the chart. The clamps pulled free and the cover came away and he looked in at the target and his eyes bulged and the pencil fell from his limp fingers. "I'll be double gosh-darned!" he whispered. Jerry could contain himself no longer but burst out laughing at his friend's astonishment "Just a joke," he gasped through the laughter. "I put some cheese in place of the rubidium."

"This is cheese?" Chuck asked, and withdrew a spherical black lump from the target area.

This time it was Jerry's turn to gape and gasp, and Chuck enjoyed a good chuckle at his friend's discomfiture. But the fun once over, they turned their attention to the sudden mystery.

"It was cheese before it was bombarded," Jerry said, suddenly serious, looking at the shiny black pellet through a strong lens.

"There are a number of unusual chemicals in my father's cheese. Somehow they united under the bombardment to form this new compound, once the large quan

tities of hydrogen and oxygen had been freed from the water. What can it be?"

"We can find out easily enough – but I have just had an idea. Take a vacuum tube. . . ."

"Of course, I had the same obvious idea. Put this new substance in place of the cathode and hook it up and see what kind of signal it produces."

"Exactly my idea." Jerry smiled. "But we need a name for this substance."

"I think cheddite fills the bill."

"Bang on!"

They cracked the glass casing of a hulking PF167 power tube and put the mysterious fragment of cheddite in place of the cathode, Jerry deftly wiring it into the circuit while Chuck took a glass rod and quickly blew a new envelope for the tube. A few moments more sufficed to wire the tube into a breadboarded amplifier circuit and to switch the power on.

"Give it some more juice," Jerry said, frowning at the meters hooked up to the output of the circuit.

"She's taking all we have now," Chuck answered, spinning the great theostat to its final stop.

"Well, then there's something mighty fishy here. Look. The current is pouring into the circuit – but it is not coming out! Not a needle has flickered from the stops. Where is all that energy going?"

Chuck scratched his wide jaw in puzzlement. "It's not coming out as volts or ohms or watts, that is for sure. So it must be radiant energy of a different kind. Let's hook up a hunk of aerial to that output and see what kind of signal it is putting out."

A handy metal coat hanger served that function well and was wired into the circuit while test instruments were set up around it.

"I'll give it just a millivolt first," Jerry said as he threw the switch.

What happened next was as soundless as it was shocking. The moment the current went into the circuit something was broadcast from the coat hanger-aerial, because a coat-hanger-shaped chunk of wall instantly vanished. It happened soundlessly and in a fraction of a second of time. Jerry hurled off the current, and they rushed to the wall. Through the new opening they could see the board fence that circled the backyard – and the same strange force had also taken a coat-hanger-shaped section from the fence as well.

"And spreading," Chuck mused. "That hole in the fence is two or three times as big as the first opening."

"Not only that," Jerry said, squinting along the edge of the hole. "If you look, you'll see a stub of a mast next door where the Grays' new color TV aerial used to be. And, let me think for a second, yes, I'm right. That missing section of fence is where the landlady's cat sleeps in the afternoon. And he was sleeping there when I came in."

"This will take some thinking out," Chuck said as they hammered boards over the opening in the wall "We had better keep it to ourselves for a while. I'll send an anonymous check to the Grays for their aerial."

"We better think about an anonymous cat for my landlady as well."

A sudden knocking on the door startled them both, and they exchanged glances, for it was the landlady calling to them. Mrs. Hosenpefer was a good woman, though advanced in years, a widow who had run her home as a boardinghouse ever since her husband, a switchman on the railroad, had met a tragic end under a boxcar that his advancing deafness had prevented hearing approach. Somewhat guiltily the two young men opened the door to face the white-haired widow wringing her hands with despair.

"I don't know what to do," she wailed, "and I know I shouldn't bother you out here, but something terrible has happened. My cat" – both listeners recoiled at the word "has been stolen. Poor Max, who would do that to a sweet harmless animal like that?"

"Just what do you mean 'stolen'?" Jerry asked, fighting desperately to keep the tension out of his voice. "I can't imagine why, some people will do awful things these days, it must be the drugs. Here I thought my Max was asleep on the fence out there" – the two listening men stirred ever so slightly at the words – "but he wasn't. Kidnapped. I just had a phone call from the sheriff in Clarktown that somebody had thrown Max through a window or something right into the middle of the Unreformed Baptist choir practice. Max was very angry and scratched the soloist. They caught him and called me because of the tag on his collar."

"This call came through now?" Jerry asked, innocently.

"Not a minute ago. I rushed right out here to ask for help."

"And Clarktown is eighty miles away," Chuck said, and the chums exchanged pregnant, significant glances.

"I know, an awful distance. How can I get my darling Max back?"

"Now don't you worry an instant," Jerry said, gently ushering the bereaved woman out. "We'll drive right over and get Max. It's in the bag." The closing door shut off her cries of gratitude, and the experimenters faced each other.

"Eighty miles!" Chuck shouted.

"Instantaneous transmission!"

"We've done it!"

"Done what?"

"I don't know – but whatever it is, I feel it is a great step forward for mankind!"

2

A SHOCKING DISCOVERY

"We'll just have to go back to the old drawing board" Chuck sighed gloomily, looking at the large hole in the ground where the boulder had been and at the larger hole in the nearby hillside. "We just can't control the cheddite projector no matter how hard we try."

"Let me have one more go," Jerry muttered as he probed the depths of the device with a long-shanked screwdriver. For security's sake they had built their invention into a small portable Japanese television set, and so cunningly contrived the inner wiring that it still functioned as a TV as well. Jerry finished his adjustment and switched the set on. There was a quick glimpse of a vampire sinking his fangs into a girl's fair neck before a secret button activated the cheddite projector. The TV screen now displayed a complex wave form which changed shape as further adjustments were made.

"I think this is it." Jerry grinned as he sighted along the aerial. "I'm going to focus on that stick and move it over by the ridge there. Here goes."

There was no sound or visible radiation from the device, but the cheddite force sprang out, unseen yet irresistible. The stick did not move. However, a great rock a hundred yards away disappeared in a fraction of a second and reappeared over the lake behind them. The sudden tumultuous splashing was followed instantly by a wave of water that washed around their ankles.

"Our problem is control." Chuck grimaced unhappily, wiping off the TV set.

"There has to be a way," Jerry said, his words as firm as the set of his jaw. "We know that the cheddite produces a wave of kappa radiation that drops anything in its field through into the lambda dimension where space time laws as we know them do not exist. It appears from the mathe.matical model you constructed that this lambda dimension, while congruent with ours in every way, is really very much smaller. What was your estimate?"

"Roughly, our spiral galaxy which is about eighty thousand light-years across is, in the lambda dimension, about a mile and a half wide."

"Right. So anything moving a short distance in the lambda dimension will have moved an incredible distance in our own dimension when it emerges. That's the theory all right, and it checks out to fifteen decimal places – but why can't we make it work?"

It was then that Jerry realized that he was talking to himself. Chuck had that glazed look in his eyes that meant his brain was churning away busily at some complex mathematical theorem. Jerry recognized the signs and smiled understandingly as he packed the cheddite projector and test equipment into the back of their battered jeep. He had just finished doing this when Chuck snapped back to reality as suddenly as he had left.

"I have it. Molecular interference."

"Of course!" Jerry said gleefully, snapping his fingers.

"It's obvious. The kappa radiation is deflected ever so minutely by the atmosphere. No wonder we couldn't control the results. We'll have to carry on the rest of the experiments in a vacuum. But it will be some job to build a big vacuum chamber."

"There's one we can use not far away," Chuck said with a chuckle. "Just one hundred miles . . ."

They burst out laughing together as Jerry pointed straight up. "You're so right – there's all the vacuum we need up there. Just a matter of getting to it."

"The Pleasantville Eagle will take care of that. We'll say that we're testing, what? Navigational equipment. They'll let us borrow her ."

The Pleasantville Eagle was the plane that flew the football team to all its games. Since it was a 747, it flew most of the spectators as well. Both Jerry and Chuck were trained pilots, as well as superb rifle shots and champion polo players, so had relieved the pilot at the controls many times. They had modified and improved most of the electronic equipment on the big plane so it seemed only natural that they would have improvements for the navigational rig as well. They would have no trouble getting permission to test fly the plane, none at all. Particularly since Chuck's dad had donated the plane to the school in the first place.

They hurried back to the lab and had just finished building the cheddite projector into a navigation frequency receiver when there came a familiar light tapping at the door. Both young men sprang to open it, scuffling goodnaturedly before throwing it wide.

"Hi," Sally Goodfellow said cheerfully, strolling in casually, a vision in a green cotton summer frock, almost the same green as her lovely eyes, her shoulder-length hair the color of golden cornsilk. "What are you two guys up to now?"

"Same old stuff," Jerry said offhandedly as Chuck winked broadly behind the girl's back. No one, they had agreed, no one was to know about the cheddite projector until they had tested it thoroughly. They had taken their oath on that, and as much as they loved Sally with every fiber of their beings, they would not break that oath.

"What old stuff?" Sally asked, not deceived for an instant.

"Improved navigation aid. You're just in time to drive us to the field so we can install it on the Eagle. We have the jeep engine apart, rebuilding it."

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

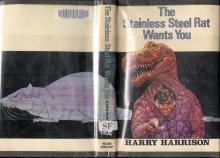

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

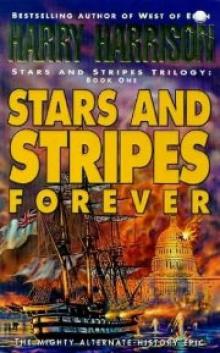

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

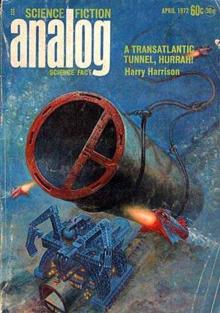

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

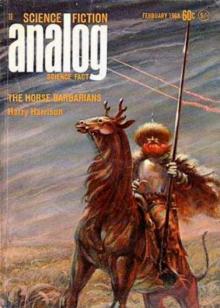

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

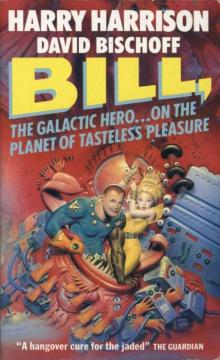

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures