- Home

- Harry Harrison

Return to Eden

Return to Eden Read online

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

RETURN TO EDEN

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE

ENVOY

THE WORLD WEST OF EDEN

YILANÈ

History of the World

Physiology

Diet

Reproduction

Science

Culture

The Eight Principles of Ugunenapsa

THE TANU

Language

THE PARAMUTAN

Environment

Language

DICTIONARIES

Yilanè–English

Marbak–English

Sesek–English

Angurpiaq–English

ZOOLOGY

This is a story of the world today.

This is our world as it would be if a meteor had not struck the Earth 65 million years ago.

The world at that time was populated by the great reptiles. They were the most successful life form that the Earth had ever seen. For over 140 million years they had ruled the land, filled the sky, swarmed in the seas. Scuttling beneath their feet were the mammals. These mammals were the ancestors of mankind. Tiny, shrew-like animals that were preyed on by the larger, faster, more intelligent saurians.

Then, 65 million years ago, this all changed. A meteor six miles in diameter struck the Earth and caused disastrous atmospheric upheavals. Within a brief span of time over seventy-five percent of the species then existent were wiped out. The age of the dinosaurs was over; the evolution of the mammals that they had suppressed for 100 million years began. The world as we know it was born.

But what would our world be like today if that meteor had not fallen?

This is the story of that world.

Today.

PROLOGUE: KERRICK

Life is no longer easy. Too much has changed, too many are dead, the winters are too long. It was not always this way. I remember clearly the encampment where I grew up, remember the three families there, the long days, friends, good food. During the warm seasons we stayed on the shore of a great lake filled with fish. My first memories are of that lake, looking across its still water at the high mountains beyond, seeing their peaks grow white with the first snows of winter. When the snow whitened our tents and the grass around as well, that would be the time when the hunters went to the mountains. I was in a hurry to grow up, eager to hunt the deer, and the greatdeer, at the hunters’ side.

That simple world of simple pleasures is gone forever. Everything has changed, and it must be said, not for the better. At times I wake up at night and wish that what happened had never happened. But these are foolish thoughts and the world is as it is, changed now in every way. What I thought was the entirety of existence has proved to be only a tiny corner of reality. My lake and my mountains are only the smallest part of this great continent that borders an immense ocean to the east.

I also know about the others, the creatures we call murgu, and I learned to hate them even before I saw them. I will tell you about them.

As our flesh is warm, theirs is chill. When you look at us you see that we have hair upon our heads. A hunter will grow a proud beard, while the animals that we hunt have warm flesh and fur or hair. But this is not true of the murgu. They are cold and smooth and scaled, have claws and teeth to rend and tear, are large and terrible, to be feared. And hated. When I was very young I learned about them, knew that they lived in the warm waters of the ocean to the south and on the warm lands to the south. They cannot abide the cold so although I grew up fearing them I also knew they could not trouble us.

All that has changed so terribly that nothing will be the same ever again. That is because there are murgu called Yilanè who are intelligent, just as we Tanu are intelligent. It has become my frightening knowledge that our world is only a tiny part of the Yilanè world. I know now that we live in the far northern part of a great continent. Know as well that to the south of us, over all the land, swarm only murgu and Yilanè.

And there is even worse. Across the ocean an even larger continent exists—and in this distant land are no hunters at all. None. Yilanè, only Yilanè. The entire world is theirs except for our small part.

Now I will tell you the worst thing about the Yilanè. They hate us as we hate them. This would not matter if they were only great, insensate beasts. We would stay in the cold north and avoid them in this manner.

But there are those among them who may be as intelligent as hunters, as fierce as hunters. And although their number cannot be counted it would be truthful to say that they fill all of the lands of this great world.

I know these things because I was captured by the Yilanè, grew up among them, learned from them. The first horror I felt when my father and all the others were killed has been dimmed by the years. When I learned to speak as the Yilanè do I became as one of them, forgot that I was a hunter, even learned to call my people ustuzou, creatures of filth. Because all order and rule among the Yilanè comes down from the top I thought very well of myself. Since I was close to Vaintè, the eistaa of the city, its ruler, I was looked upon as a ruler myself.

The living city of Alpèasak was newly grown on these shores, settled by Yilanè from across the ocean. They had been driven from their own distant city by the winters that grow colder every year. The same cold that had driven my father and the other Tanu south in the search for food sent the Yilanè questing across the sea. They came here and they grew their city on our shores. When they found the Tanu who were here before them they killed them. Just as the Tanu killed Yilanè on sight. It is a shared hatred.

For many years I had no knowledge of this. I grew up among the Yilanè and I thought as they did. When they made war I looked upon the enemy as filthy ustuzou, not Tanu, my brothers. This changed only when I met the prisoner, Herilak. A sammadar, a leader of the Tanu, who understood me far better than I understood myself. When I spoke to him as enemy, alien, he spoke to me as flesh of his flesh. As the language of my childhood returned so did my memories of that warm earlier life. Memories of my mother, family, friends. There are no families among the Yilanè, no suckling babies among egg-laying lizards, no possible friendships where these cold females rule, where the males are locked away from the sight of all the others for their entire lifetime.

Herilak showed me that I was Tanu, not Yilanè. Because of this I freed him and we fled. At first I regretted it—but there was no going back. For in escaping I had attacked and almost killed Vaintè, she who rules. I joined the sammads, the family groups of the Tanu, joined them in flight from the onslaught of those who had once been my companions. But I had other companions now, and friendship of a kind I could never know among the Yilanè.

I had Armun, she who came to me and showed me that which I had never even known, awoke the feelings I could never have felt while I was living among that alien race. Armun who bore our son.

But we still led our lives under the constant threat of death. Vaintè and her warriors followed the sammads without mercy. We fought back—and sometimes won, even capturing some of their living weapons, the death-sticks that kill creatures of any size. With these we could penetrate far to the south, eating well of the teeming murgu, killing the vicious ones when they attacked. Only to flee again when Vaintè and her endless supply of killers from across the sea found us and fought to kill us.

This time the survivors went where we could not be followed, across the frozen mountain ranges to the land beyond. Yilanè cannot live in the snows; we thought we would be safe.

And we were, for a long time we were. Beyond the mountains we found Tanu who did not live by hunting alone, but who grew crops in their hidden valley and could make pots, weave cloth and do many other wondrous things. They are the Sasku and they are our friends, for they worship the god of the mastodon. We brought our mastodons to them and we have been as one people ever since. Life was good in the Sasku valley.

Until Vaintè found us once again.

When this happened I realized that we could run no more. Like cornered animals we must turn and fight. At first none would listen to me for they did not know the enemy as I did. But they came to understand that the Yilanè had no knowledge of fire. They would learn of it when we brought the torch to their city.

And this is what we did. Burnt their city of Alpèasak and sent the few survivors fleeing back to their own world and to their own cities across the sea. Among those who lived was Enge who had been my teacher and my friend. She did not believe in killing as all the others did, and was the leader of a group who called themselves the Daughters of Life, believers in the sanctity of life. Would that they had been the only survivors.

But Vaintè lived as well. This creature of hatred survived the destruction of her city, fled on the uruketo, the great living vessel of the Yilanè, vanished into the trackless ocean.

I put her from my mind because of more urgent matters. Although all the murgu in the city were dead, most of the burned city had survived. The Sasku wished to stay with me in the city, but the Tanu hunters returned to their sammads. I could not go back with them for the part of me that thinks like a Yilanè kept me in this Yilanè city. That and the fact that two of their males had survived the destruction. I was drawn to this half-ruined city, and to them, and forgot my responsibility to Armun and my son. It must be truthfully said that this selfishness nearly led to their destruction.

We labored to make this murgu city one in which we could live, and we succeeded. But in vain. Vaintè had found new allies across the ocean and returned once again. Armed with the invincible Yilanè science. No attacks with weapons this time, but poison plants and animals instead. And even as the attacks began the sammads returned from the north. Their death-sticks had died in the winter and they could not survive without them. Here in the city we had these deadly creatures, so here the sammads must remain despite the slow approach of Yilanè destruction.

The sammads brought me even crueler news. Since I had not returned to her, Armun had tried to return to me. She and our son were lost in the deadly winter.

I would have ended my life then were it not for one tiny spark of hope. A hunter who traded far to the north, with the Paramutan who live in that frozen wasteland, had heard that a Tanu woman and child had been seen among them. Could it be them? Could they still be alive? The fate of the city and the Tanu and Sasku living in it meant nothing to me now. I had to go north and search for them. Ortnar, my friend and strong right arm, understood this and went with me.

Instead of Armun we almost found death. Had the Paramutan not discovered us it would have ended there. We survived, although Ortnar is still crippled by his frozen feet. The hunters of the ice saved us, and to my great joy Armun was with them. Then, in the spring, they brought us safely back to the city in the south.

Which was Yilanè once again. The sammads and the Sasku had retreated to the distant Sasku valley and were being followed closely by Vaintè and her forces, dark portents of certain death. And I could do nothing. My little sammad and the two Yilanè males were safe enough for the moment at our hidden lake. But the others would die and I could not save them.

It would be difficult enough to save ourselves for it was a certainty that one day our hiding place would be found. I knew that the Paramutan who had brought us here would soon be crossing the ocean to hunt upon the far shore. Perhaps there might be safety there. Armun and I joined them and crossed the sea—only to discover that the Yilanè were there ahead of us. But from death came life. We destroyed them, and in doing so I discovered where Ikhalmenets was, the city on the island which was aiding Vaintè in her war of destruction.

What I did was either very brave or very foolhardy. Perhaps both. I forced the eistaa of Ikhalmenets to stop the attack, to stop Vaintè at the very brink of her victory. In this I succeeded and the world is again at peace. My sammad is once more joined and complete at our hidden lake. The battle is ended.

Yet there were other things that had happened that I did not discover for a long, long time. Enge, my teacher and my friend, was still alive. She and her followers, the Daughters of Life, had found refuge in a new land far to the south. They had grown a city there far from the other Yilanè who wished to see their destruction. Another place of peace, another end to strife.

But there was yet another thing that I did not know. That creature of hatred and death, Vaintè, was still alive.

That is what has happened in the past. Now I stand by our hidden lake squinting into the sunset, trying to see what will happen in the years to come.

Uveigil as lok at mennet, homennet thorpar ey wat marta ok etin.

MARBAK PROVERB

* * *

No matter how clear the river, there is always some darkness upstream drifting down towards you.

ONE

There was silence and peace.

It had been a hot day, for the days were always warm here. But the evening air was a little cooler with the light breeze blowing over the water. Kerrick squinted into the sun, wiped some of the perspiration from his face. It was easy to forget the slow changing of the seasons of the year this far to the south. The sun, as always, was setting behind the lake, the last glint of it shining on the unruffled waters, with the red sky reflected there as well. A fish stirred the surface and waves of color moved out in all directions. This was the way it always was, unchanging. Sometimes there would be clouds, or rain, but no really cold weather, no slow cycle of seasons. The rain and fog were an indication of winter. Then the air was cooler at night as well. But there was never the fresh green of spring grass, the russet of leaves in the autumn.

Never the deep snow of winter; there were some things that Kerrick did not miss at all. In damp weather his fingers still ached where they had been frozen. Far better the heat than the snow. He squinted at the vanishing sun, a tall, erect man. His long, pale hair reached to his shoulders, was bound about his forehead by a thin band of leather. In recent years wrinkles had formed at the corners of his eyes; there were pale scars of old wounds on his tanned skin as well. He turned to look as the water moved in larger waves as something dark broke the surface just offshore. There was a familiar rumbling snort that Kerrick recognized. Schools of hardalt came close to the surface at dusk and Imehei had grown adept at netting them in the failing light. He came ashore now, puffing and blowing, with a netful of the creatures. Red reflections glinted on their shells, their tentacles trailed down his back. He dropped them before the shelter where the two Yilanè males slept and called out attention to speaking, firm authority in his voice. Nadaske emerged and expressed sounds of approval as they opened the net. There was peace in sammad Kerrick—but still peace at a distance. The Yilanè stayed on their side of the grass clearing, t

he Tanu on theirs. Only Kerrick and Arnwheet were at home in both.

Kerrick frowned at the thought and rubbed his fingers through his beard, ran them along the metal ring about his neck. He knew that Armun was not pleased that Arnwheet visited the Yilanè. To her the males were just murgu, creatures that would be better off dead and forgotten rather than waddling about, repulsive companions to their son. But she was wise enough not to speak of it. On the surface at least there was peace in the sammad. Now she emerged from the tent that was sheltered under the trees, saw Kerrick sitting there, came and joined him at the water’s edge.

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

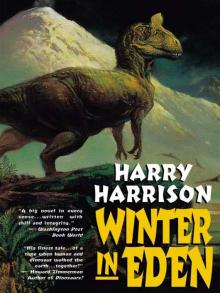

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

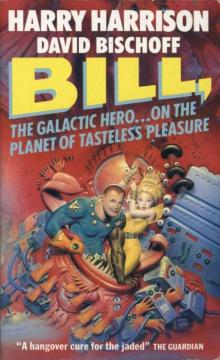

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures