- Home

- Harry Harrison

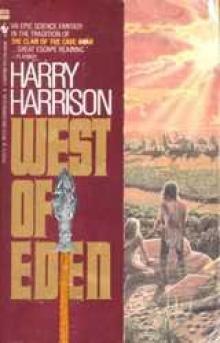

West of Eden

West of Eden Read online

CONTENTS

BOOK ONE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

BOOK TWO

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE

THE WORLD WEST OF EDEN

YILANÈ

History of the World

The Early Years

Physiology

Diet

Reproduction

Science

Culture

TANU

ZOOLOGY

for

T. A. Shippey and Jack Cohen

without whose aid this book would never have been written

particular thanks as well to

John R. Pierce and Leon E. Stover

8 And the LORD God planted a garden eastward in Eden; and there he put the man whom he had formed.

16 And Cain went out from the presence of the LORD, and dwelt in the land of Nod, on the east of Eden.

GENESIS

The great reptiles were the most successful life forms ever to populate this world. For 140 million years they ruled the Earth, filled the sky, swarmed in the seas. At this time the mammals, the ancestors of mankind, were only tiny, shrew-like animals that were preyed upon by the larger, faster, more intelligent saurians.

Then, 65 million years ago, this all changed. A meteor six miles in diameter struck the Earth and caused disastrous atmospheric upheavals. Within a brief span of time over seventy-five percent of all the species then existent were wiped out. The age of the dinosaurs was over; the evolution of the mammals that they had suppressed for 100 million years began.

But what if that meteor had not fallen?

What would our world be like today?

PROLOGUE: KERRICK

I have read the pages that follow here and I honestly believe them to be a true history of our world.

Not that belief was easy to come by. It might be said that my view of the world was a very restricted one. I was born in a small encampment made up of three families. During the warm seasons we stayed on the shore of a great lake rich with fish. My first memories are of that lake, looking across its still water at the high mountains beyond, seeing their peaks grow white with the first snows of winter. When the snow whitened our tents, and the grass around as well, that would be the time when the hunters went to the mountains. I was in a hurry to grow up, eager to hunt the deer, and the greatdeer, at their side.

That simple world of simple pleasures is gone forever. Everything has changed—and not for the better. At times I wake at night and wish that what happened had never happened. But these are foolish thoughts and the world is as it is, changed now in every way. What I thought was the entirety of existence has proved only to be a tiny corner of reality. My lake and my mountains are only the smallest part of a great continent that stretches between two immense oceans. I knew of the western ocean because our hunters had fished there.

I also knew about the others and learned to hate them long before I ever saw them. As our flesh is warm, so is theirs cold. We have hair upon our heads and a hunter will grow a proud beard, while the animals that we hunt have warm flesh and fur or hair, but this is not true of Yilanè. They are cold and smooth and scaled, have claws and teeth to rend and tear, are large and terrible, to be feared. And hated. I knew that they lived in the warm waters of the ocean to the south and on the warm lands to the south. They could not abide the cold so did not trouble us.

All that has changed and changed so terribly that nothing will ever be the same again. It is my unhappy knowledge that our world is only a tiny part of the Yilanè world. We live in the north of a great continent that is joined to a great southern continent. And on all of this land, from ocean to ocean, there swarm only Yilanè.

And there is even worse. Across the western ocean there are even larger continents—and there there are no hunters at all. None. But Yilanè, only Yilanè. The entire world is theirs except for our small part.

Now I will tell you the worst thing about the Yilanè. They hate us just as we hate them. This would not matter if they were only great, insensate beasts. We would stay in the cold north and avoid them in this manner.

But there are those who may be as intelligent as hunters, as fierce as hunters. And their number cannot be counted but it is enough to say that they fill all of the lands of this great globe.

What follows here is not a nice thing to tell, but it happened and it must be told.

This is the story of our world and of all of the creatures that live in it and what happened when a band of hunters ventured south along the coast and what they found there. And what happened when the Yilanè discovered that the world was not theirs alone, as they had always believed.

WEST

of

EDEN

BOOK ONE

Isizzô fa klabra massik, den sa rinyur meth alpi.

Spit in the teeth of winter, for he always dies in the spring.

CHAPTER ONE

Amahast was already awake when the first light of approaching dawn began to spread across the ocean. Above him only the brightest stars were still visible. He knew them for what they were; the tharms of the dead hunters who climbed into the sky each night. But now even these last ones, the best trackers, the finest hunters, even they were fleeing before the rising sun. It was a fierce sun here this far south, burningly different from the northern sun that they were used to, the one that rose weakly into a pale sky above the snow-filled forests and the mountains. This could have been another sun altogether. Yet now, just before sunrise, it was almost cool here close to the water, comfortable. It would not last. With daylight the heat would come again. Amahast scratched at the insect bites on his arm and waited for dawn.

The outline of their wooden boat emerged slowly from the darkness. It had been pulled up onto the sand, well beyond the dried weed and shells that marked the reach of the highest tide. Close by it he could just make out the dark forms of the sleeping members of his sammad, the four who had come with him on this voyage. Unasked, th

e bitter memory returned that one of them, Diken, was dying; soon they would be only three.

One of the men was climbing to his feet, slowly and painfully, leaning heavily on his spear. That would be old Ogatyr; he had the stiffness and ache in his arms and legs that comes with age, from the dampness of the ground and the cold grip of winter. Amahast rose as well, his spear also in his hand. The two men came together as they walked towards the water holes.

“The day will be hot, kurro,” Ogatyr said.

“All of the days here are hot, old one. A child could read that fortune. The sun will cook the pain from your bones.”

They walked slowly and warily towards the black wall of the forest. The tall grass rustled in the dawn breeze; the first waking birds called in the trees above. Some forest animal had eaten the heads off the low palm trees here, then dug beside them in the soft ground to find water. The hunters had deepened the holes the evening before and now they were brimming with clear water.

“Drink your fill,” Amahast ordered, turning to face the forest. Behind him Ogatyr wheezed as he dropped to the ground, then slurped greedily.

It was possible that some of the creatures of the night might still emerge from the darkness of the trees so Amahast stood on guard, spear pointed and ready, sniffing the moist air rich with the odor of decaying vegetation, yet sweetened by the faint perfume of night-blooming flowers. When the older man had finished he stood watch while Amahast drank. Burying his face deep in the cool water, rising up gasping to splash handfuls over his bare body, washing away some of the grime and sweat of the previous day.

“Where we stop tonight, that will be our last camp. The morning after we must turn back, retrace our course,” Ogatyr said, calling over his shoulder while his eyes remained fixed on the bushes and trees before him.

“So you have told me. But I do not believe that a few days more will make any difference.”

“It is time to return. I have knotted each sunset onto my cord. The days are shorter, I have ways of knowing that. Each sunset comes more quickly, each day the sun weakens and cannot climb as high into the sky. And the wind is beginning to change, even you must have noticed that. All summer it has blown from the southeast. No longer. Do you remember last year, the storm that almost sank the boat and blew down a forest of trees? The storm came at this time. We must return. I can remember these things, knot them in my cord.”

“I know you can, old one.” Amahast ran his fingers through the wet strands of his uncut hair. It reached below his shoulders, while his full blond beard rested damply on his chest. “But you also know that our boat is not full.”

“There is much dried meat . . .”

“Not enough. We need more than that to last the winter. The hunting has not been good. That is why we have journeyed farther south than we ever have before. We need the meat.”

“One single day, then we must return. No more than that. The path to the mountains is long and the way hard.”

Amahast did not speak in answer. He respected Ogatyr for all the things that the old man knew, his knowledge of the correct way to make tools and find magic plants. The oldster knew the rituals needed to prepare for the hunt, as well as the chants that could ward off the spirits of the dead. He had all of the knowledge of his lifetime and of the lifetimes before him, the things that he had been told and that he remembered, that he could recite from the rising of the sun in the morning to the setting at night and still not be done. But there were new things that the old one did not know about, and these were what troubled Amahast, that demanded new answers.

It was the winters that were the cause of it, the fierce winters that would not end. Twice now there had been the promise of spring as the days had grown longer, the sun brighter—but spring had never come. The deep snows had not melted, the ice on the streams stayed frozen. Then there had been hunger. The deer and the greatdeer had moved south, away from their accustomed valleys and mountain meadows that now stayed tight-locked in winter’s unyielding grip. He had led the people of his sammad as they had followed the animals, they had to do that or starve, down from the mountains to the broad plains beyond. Yet the hunting had not been good, for the herds had been thinned out by the terrible winter. Nor was their sammad the only one that had troubles. Other sammads had been hunting there as well, not only ones that his people were joined to by marriage, but sammads they had never seen before. Men who spoke Marbak strangely, or not at all, and pointed their spears in anger. Yet all of the sammads were Tanu, and Tanu never fought Tanu. Never before had they done this. But now they did and there was Tanu blood on the sharp stone points of the spears. This troubled Amahast as much as did the endless winter. A spear for hunting, a knife for skinning, a fire for cooking. This was the way it had always been. Tanu did not kill Tanu. Rather than commit this crime himself he had taken his sammad away from the hills, marching each day towards the morning sun, not stopping until they had reached the salt waters of the great sea. He knew that the way north was closed, for the ice there came to the ocean’s edge and only the Paramutan, the skin-boat people, could live in those frozen lands. The way south was open but there, in the forests and jungles where the snow never came, were the murgu. And where they were was death.

So only the wave-filled sea remained. His sammad had long known the art of making wooden boats for summer fishing, but never before had they ventured out of sight of land or away from their camp upon the beach. This summer they must. The dried squid would not last the winter. If the hunting were as bad as that of the winter before then none of them would be alive in the spring. South, then, it must be south, and that was the way they had gone. Hunting along the shore and on the islands off the coast, in fear always of the murgu.

The others were awake now. The sun was above the horizon and the first shrieks of the animals were sounding from the depths of the jungle. It was time to put to sea.

Amahast nodded solemnly when Kerrick brought him the skin bag of ekkotaz, then dipped out a handful of the thick mass of crushed acorns and dried berries. He reached out with his other hand and ruffled the thick mat of hair on his son’s head. His firstborn. Soon to be a man and take a man’s name. But still a boy, although he was growing strong and tall. His skin, normally pale, was tanned golden now since, like all of them on this voyage, he wore only a deerskin tied at his waist. About his neck, hung from a leather thong, there was a smaller version of the skymetal knife that Amahast also wore. A knife that was not as sharp as stone but was treasured for its rarity. These two knives, the large and small, were the only skymetal the sammad possessed. Kerrick smiled up at his father. Eight years old and this was his first hunt with the men. It was the most important thing that had ever happened to him.

“Did you drink your fill?” Amahast asked. Kerrick nodded. He knew there would be no more water until nightfall. This was one of the important things that a hunter had to learn. When he had been with the women—and the children—he had drunk water whenever he had felt thirsty, or if he had been hungry he had nibbled at the berries or eaten the fresh roots as they dug them up. No more. He went with the hunters now, did what they did, went without food and drink from before sunrise until after dark. He gripped his small spear proudly and tried not to start with fright when something crashed heavily in the jungle behind him.

“Push out the boat,” Amahast ordered.

The men needed no urging; the sounds of the murgu were growing louder, more threatening. There was little enough to load into the boat, just their spears, bows and quivers of arrows, deerskins, and bags of ekkotaz. They pushed the boat into the water and big Hastila and Ogatyr held it steady while the boy climbed in carefully holding a large shell that contained glowing embers from the fire.

Behind them on the beach Diken struggled to rise, to join the others, but he was not strong enough today. His skin paled with the effort and great drops of perspiration stood out on his face. Amahast came and knelt beside him, took up a corner of the deerskin that he was lying on and wiped the

wounded man’s face.

“Rest easy. Well put you into the boat.”

“Not today, not if I cannot climb aboard myself.” Diken’s voice was hoarse, he gasped with the effort of speech. “It will be easier if I wait here for your return. It will be easier on my hand.”

His left hand was now very bad. Two fingers had been bitten, torn away, when a large jungle creature had blundered into their camp one night, a half-seen form that they had wounded with spears and driven back into the darkness. At first Diken’s wound had not looked too serious, hunters had lived with worse, and they had done all the things for him that could be done. They had washed the wound in sea water until it bled freely, then Ogatyr had bound it up with a poultice made from the benseel moss that had been gathered in the high mountain bogs. But this time it had not been enough. The flesh had grown red, then black, and finally the blackness had spread up Diken’s arm; its smell was terrible. He would die soon. Amahast looked up from the swollen arm to the green wall of the jungle beyond.

“When the beasts come my tharm will not be here to be consumed by them,” Diken said, seeing the direction of Amahast’s gaze. His right hand was clenched into a fist; he opened and closed it briefly to disclose the flake of stone concealed there. The kind of sharp chip that was used to butcher and skin an animal. Sharp enough to open a man’s vein.

Amahast rose slowly and rubbed the sand from his bare knees. “I will look for you in the sky,” he said, his expressionless voice so low that only the dying man could hear it.

“You were always my brother,” Diken said. When Amahast left he turned his face away and closed his eyes so he would not see the others leave and perhaps give some sign to him.

The boat was already in the water when Amahast reached it, bobbing slightly in the gentle swell. It was a good, solid craft that had been made from the hollowed-out trunk of a large cedar tree. Kerrick was in the bow, blowing on the small fire that rested on the rocks there. It crackled and flamed up as he added more bits of wood to it. The men had already slipped their oars between the thole pins, ready to depart. Amahast pulled himself in over the side and fitted his steering oar into place. He saw the men’s eyes move from him to the hunter who remained behind upon the beach, but nothing was said. As was proper. A hunter did not show pain—or show pity. Each man has the right to choose when he will release his tharm to rise up to erman, the night sky, to be welcomed by Ermanpadar, the sky-father who ruled there. There the tharm of the hunter would join the other tharms among the stars. Each hunter had this right and no other could speak about it or bar his way. Even Kerrick knew that and was as silent as the others. “Pull,” Amahast ordered. “To the island.”

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

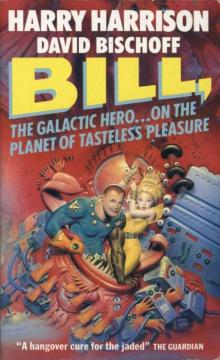

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures