- Home

- Harry Harrison

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 Page 7

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 Read online

Page 7

At least he was doing the right thing now. Getting the Ragnarssons on your side—that could never be a bad idea. Hjörvarth was coming to the end of his tale. Sigvarth turned in his chair and nodded at his two henchmen waiting near the entrance. They nodded back and hastened out.

“…so we burned the wagons on the shore, threw in a couple of churls that my father in his wisdom had kept back, as sacrifice to Aegir and to Ran, boarded ship, ran down the coast to the rivermouth—and here we are! The men of the Small Isles, under famous Sigvarth Jarl—and I his lawful son Hjörvarth—at your service, sons of Ragnar, and ready for more!”

The tent erupted in applause, horns banged on tables, feet stamped, knives clashed. The men were in a good temper at this fair start to the campaign.

The Snake-eye rose to his feet and spoke.

“Well, Sigvarth, we said you could keep your plunder, and you have earned it, so you need have no fear of telling us your good luck. Tell us, how much did you take? Enough to retire and buy yourself a summer home in Sjaelland?”

“Little enough, little enough,” called Sigvarth, to groans of disbelief. “Not enough to make me turn farmer. There are only poor pickings to be expected from country thanes. Wait till the great, the invincible Army sacks Norwich. Or York! Or London!” Cries of approval now, and a smile from the Snake-eye. “It is the ministers we must sack, full of gold which the Christ-priests have wrung from the fools of the South. No gold and little silver from the countryside.

“But some things we did take, and I am ready to share the best of it. Here, let me show you the finest thing that we found!”

He turned and waved his followers in. They pushed through the tables, leading with them a figure draped completely in sacking, a rope round its waist. The figure was pushed to the front of the center table, and then in two movements the rope was cut, the sacking whisked away.

Godive emerged blinking into the light, facing a horde of bearded faces, open mouths, clutching hands. She shrank back, tried to turn away, and found herself staring into the eyes of the tallest of the chieftains, a pale man, no expression on his face and eyes like ice, eyes that never blinked. She turned again, looking almost with relief at Sigvarth, the only face she could even recognize.

In this cruel company she was like a flower in a patch of dank undergrowth. Pale hair, fine skin, full lips more attractive now as they parted with fear. Sigvarth nodded again, and one of his men ripped down at the back of her gown. Tearing at it until the fabric tore, then stripping it from her despite screams and struggles until the young girl stood naked but for her shift, her youthful body clear for all to see. In an agony of fear and shame she crossed her hands over her breasts and hung her head, waiting for whatever they would do with her.

“I will not share her,” called out Sigvarth. “She is too precious for sharing. So I will give her away! I give her to the man who chose me for this expedition, in thanks and in hope. May he use her well, and long, and vigorously. I give her to the man who chose me out, wisest of all the Army. It is to you I give her. You, Ivar!”

Sigvarth ended with a shout, and a raise of his horn. Slowly he realized that there was no answering shout, only a confused murmur, and that from the men farthest away from the center, the ones who, like him, knew the Ragnarssons least and were the latest comers to the Army. No horns were raised. Faces seemed suddenly troubled, or blank. Men looked away.

The chill at Sigvarth's heart came back. Maybe he should have asked first, he thought to himself. Maybe something was going on that he didn't know about. But where could the harm be in this? He was giving away a piece of plunder, one that any man would be glad to own, doing it publicly and honorably. Where could be the harm in making a gift of this girl, a maiden—a beautiful maiden—to Ivar? Ivar Ragnarsson. Nicknamed—Oh, Thor aid him, why was he so nicknamed? A terrible thought possessed Sigvarth. Was there meaning in that nickname?

The Boneless.

Chapter Five

Five days later, Shef and his companion lay in the slight shelter of a copse, staring across flat watermeadows to the earthworks of the Viking camp a long mile away. For the moment, at least, their nerve had failed.

They had had no trouble getting away from ruined Emneth, which normally might have been the most difficult task for the runaway slave. But Emneth had had troubles of its own. No one in any case considered himself Shef's master, and Edrich, who might have thought it his duty to keep anyone from going over to the Vikings, seemed to have washed his hands of the whole business. Without opposition, Shef had gathered his few possessions, quietly lifted a small store of food which he kept in an outlying shelter, and had made his preparations to leave.

Still, someone had noticed. As he stood hesitating over whether to bid a farewell to his mother, he had become aware of a slight figure standing silently next to him. It was Hund, boyhood friend, child of slaves on both sides, perhaps the least important and lowest ranking person in the whole of Emneth. Yet Shef had learned to value him. There was no one who knew the marshes better, not even Shef. Hund could slide through the water and take moorhens on their nests. In the foul and crowded hut he shared with his parents and their litter of children there was often an otter cub playing. The very fish seemed to come to his hands to be caught without rod or line or net. As for the herbs of the countryside, Hund knew them all, their names, their uses. Already—though he was two winters younger than Shef—the humble folk were beginning to come to him for simples and for cures. In time to come he might be the cunning man of the district, respected and feared even by the mighty. Or action might be taken against him. Even the kindly Father Andreas, Shef's preserver, had several times been seen to look at him with doubt in his eyes. Mother Church had no love for competitors.

“I want to come,” Hund had said.

“It will be dangerous,” Shef had replied.

Hund had said nothing, as was his custom when he felt nothing more needed to be said. It was dangerous to stay in Emneth too. And Shef and Hund, in their different ways, increased each other's chances.

“If you are coming you will have to get that collar off,” Shef had said, glancing at the iron collar which had been fitted round Hund's neck at puberty. “Now is the time. No one is interested in us. I'll get some tools.”

They had sought shelter in the marsh, not wanting to draw attention. It had been a difficult business getting the collar off even so. Shef had filed through it, first putting rags inside the collar to save Hund's neck from rasps, but once broken through it had been hard to get the tongs inside the circlet to bend it open. In the end Shef had lost patience, wrapped the rags round his hands, and pulled the collar open by main strength.

Hund had rubbed the calluses and weals where the iron had worn his neck and stared at the U-shape of the bent collar. “Not many men could do that,” he had observed.

“Need will make the old wife trot,” Shef had answered dismissively. Yet secretly he was pleased. He was coming into his strength, he had faced a grown warrior in battle, he was free to go where he would. He did not yet know how he could do it, but there must be a way to free Godive, and then leave the disasters of his family behind.

They had set out without further words. But trouble had begun at once. Shef had expected to have to dodge a few inquisitive people, sentries, maybe levies heading for the muster. Yet from the first day of travel he had realized that the whole countryside was beginning to buzz like a wasps' nest stirred with a stick. Men cantered down every road. Outside every village groups waited, armed and hostile, suspicious of every stranger. After one such group had decided to hold them, ignoring their story of being sent to borrow cattle from a relative of Wulfgar's, they had had to break and run for it, dodging spears and outdistancing their pursuers. But clearly orders had gone out and the folk of East Anglia had for once decided to obey wholeheartedly. There was fury in the air.

For the last two days Shef and Hund had crept through the fields and hedges, going painfully slowly, often on their belli

es in the mud. Even so, they had seen patrols out, some of them horsemen commanded by a thane or a king's companion, but others—and these the more dangerous ones—moved quietly on foot like themselves, armor and weapons padded to prevent jingle or clink; marshmen in the lead, carrying bows and hunters' slings for ambush or stalk. They meant, Shef realized, to keep the Vikings in, or at least to prevent them coming out in small parties for private plunder. But at the same time they would be only too happy to catch and hold, or kill, anyone they thought might have any intention of giving the Vikings aid, information, or reinforcement.

Only in the last couple of miles had the danger receded; and that, the pair soon understood, was only because they were now within the range of the Vikings' own patrols—these easier to avoid, but at the same time more menacing. They had spotted one group of men waiting silently within the borders of a small wood, maybe fifty of them, all mounted, all armored, great axes resting on shoulders, the man-killing battle-spears bristling above them like a gray-tipped thorn thicket. Easy to see, quite easy to avoid. But it would take a full-scale incursion by the English to drive them off or defeat them. The village patrols would stand no chance.

These were the men to whose mercy they now had to trust themselves. It did not seem as easy now as it had at Emneth. To begin with, Shef had had a vague idea of reaching the camp and declaring his relationship to Sigvarth. But there would be far too much chance of being recognized, even from the few seconds of contact they had had. It was terrible luck that had brought him into hand-to-hand combat with the one person in the camp who might—or might not—have accepted him. But now Sigvarth was one person they had to avoid at all costs.

Would the Vikings accept recruits? Shef had an uneasy feeling that much more would be needed than willingness and a hand-forged sword. But they could always use slaves. Again, Shef had an uneasy feeling that he himself might do for a laborer or galley-slave in some far-off country. But Hund had nothing visibly valuable about him. Might the Vikings just let him go, like a fish that was too small for the pan? Or would they take the easy way out of dealing with an encumbrance? The evening before, when they had first caught sight of the camp, the two youths' keen eyes saw a party come out of one of the gates and start digging a hole. A little later there had been no doubt about the contents of the cart that creaked out and emptied a dozen bodies unceremoniously down the pit. Pirates' camps had a high wastage rate.

Shef sighed. “It doesn't look any better than it did last night,” he said. “But we'll have to move sometime.”

Hund gripped is arm. “Wait. Listen. Can you hear something?”

The sound strengthened as the two youths turned their heads this way and that. Noise. Song. Many men singing together. The sound, they realized, was coming from the other side of a slight rise maybe a hundred yards to their left, where the watermeadows ran into a tangle of uncultivated common.

“It sounds like the monks singing at the great minster at Ely,” murmured Shef. A foolish thought. There would be neither monk nor priest left within twenty miles of this place.

“Shall we look?” whispered Hund. Shef made no reply, but began to crawl slowly and carefully toward the sound of deep-voiced singing. It could only be the pagans in this spot. But maybe a small group of them would be easier to approach than the whole army. Anything was better than simply walking out across that flat plain.

After they had covered half the distance on their bellies, Hund gripped Shef's wrist. Silently he pointed up a slight slope. Twenty yards away, beneath a huge old hawthorn, stood a man, motionless, his eyes scanning the ground. He leaned on an axe two-thirds his own weight. A burly man, thick-necked, broad across paunch and hip.

At least he did not seem built for speed, Shef reflected. And he was standing in the wrong place if he wanted to be a sentry. The two youths exchanged a glance. The Vikings might be great seamen. They had much to learn about the art of stealth.

Gently Shef snaked forward, angling away from the sentry, round a thicket of bracken, between and beneath a tangle of gorse, Hund crawling immediately behind him. Ahead, the noise of singing had ceased. Replaced by a single voice talking. Not talking. Exhorting. Preaching. Could there be secret Christians even among the heathen? Shef wondered.

A few yards on, he parted the bracken stems and peered silently down into a little dell, hidden from view. There, forty or fifty men sat on the ground in a rough circle. All carried swords or axes, but their spears and shields were propped up or planted in the ground. They sat within a corded-off enclosure made of a dozen spears with a thread running between them. From the thread, at intervals, dangled clumps of the bright red berry that the English called “quickbeam,” now in autumn brilliance. At the center of the enclosure, with the men seated round it, a fire burned. Next to it was planted a single spear, point up, its shaft gleaming silver.

One man stood by the fire and the spear, his back to the hidden watchers, speaking to the men round him in tones of persuasion, of command. Unlike the others, and unlike anyone else Shef had ever seen, his tunic and breeches were neither natural homespun in color nor dyed green or brown or blue, but a brilliant white, white as the inside of an egg.

From his right hand there dangled a hammer, short-hafted, double-headed—a blacksmith's hammer. Shef's keen sight locked on the front row of sitting men. Round every neck, a chain. On every chain, a pendant displayed on the chest. They were of different kinds: he could see a sword, a horn, a phallus, a boat. But at least half the men wore the sign of a hammer.

Shef rose abruptly from his concealment and walked forward into the dell. As they saw him, fifty men leap simultaneously to their feet, swords coming out, voices raised in warning. A grunt of amazement behind him, a crashing of feet through the bracken. The sentry was behind him now, Shef knew. He did not turn to look.

Slowly the man in white turned to meet him, the two facing each other across the berry-fringed thread, looking each other up and down.

“And where are you come from?” said the man in white. He spoke English with a strong, burring accent.

What shall I say? thought Shef. From Emneth? From Norfolk? That will mean nothing to them. “I come from the North,” he said aloud. The faces in front of him changed. Surprise? Recognition? Suspicion?

The man in white gestured his followers to hold still. “And what is your business with us, the followers of the Asgarthsvegr, the Asgarth Way?”

Shef pointed to the hammer in the other's hand, the hammer-pendant round his neck. “I am a smith, like you. My business is to learn.”

Someone was translating his words now to the others. Shef realized Hund had materialized at his left, and there was a threatening presence just behind them both. He kept his eyes fixed on those of the man in white. “Show me a sign of your craft.”

Shef pulled his sword from its sheath and passed it over, as he had to Edrich. The hammer-bearer turned it over and over, looked at it intently, flexed it gently, noting the surprising play in the thick, single-edged blade, scratched with his thumbnail at the surface discoloration of old rust. Carefully, he shaved a patch of hair from his forearm.

“Your forge was not hot enough,” he remarked. “Or you lost patience. Those steel strips were not even when you twisted them. But it is a good blade. It is not what it seems. And neither are you. Now tell me, young man—and remember, death is just behind you—what it is that you want? If you are just a runaway slave like your friend”—he gestured toward Hund's neck, with the telltale marks on it—“maybe we will let you go. If you are a coward who wants to join the winning side, maybe we will kill you. But maybe you are something else. Or someone else. Say then, what do you want?”

I want Godive back, thought Shef. He looked into the pagan priest's eyes and said, with all the sincerity he could muster, “You are a master-smith. The Christians will let me learn no more. I want to be your apprentice. Your learning-knave.”

The man in white grunted, handed back Shef's sword, bone hilt first. “Lower your a

xe, Kari,” he said to the man behind the pair. “There is more here than meets the eye.

“I will take you as a knave, young man. And if your friend has any skill, he may join us too. Sit, both of you, to one side, till we have finished what we were doing. My name is Thorvin, which is to say, ‘the friend of Thor,’ the god of the smiths. What are yours?”

Shef flushed with shame, dropped his eyes.

“My friend's name is Hund,” he said, “which is to say, ‘dog.’ And I too, I have only a dog's name. My father—No, I have no father. They call me Shef.”

For the first time Thorvin's face showed surprise, and more. “Fatherless?” he muttered. “And your name is Shef. But that is not only a dog's name. Truly you are uninstructed.”

Shef felt his spirits sinking as they moved toward the camp. He was not afraid for himself, but for Hund. Thorvin had told the pair of them to sit to one side while they finished their strange meeting: first him talking, then some kind of discussion in the burring Norse Shef could almost follow, and then a skin of some drink passed ceremoniously from hand to hand. At the end all the men had gathered in little groups and joined hands in silence on one object or another: Thorvin's hammer, a bow, a horn, a sword, what looked like a dried horse's penis. No one had touched the silver spear till Thorvin had gone over, pulled it briskly into two parts and rolled them up in a cloth bag. A few moments later the enclosure had been broken up, the fire put out, the spears reclaimed, the men of the group already drifting away in fours and fives, moving warily and taking different directions.

“We are followers of the Way,” Thorvin had said in partial explanation to the two youths, still speaking his careful English. “Not everyone wishes to be known as such—not in the camp of the Ragnarssons. Me they accept.” He tugged at the hammer pendant on his chest. “I have a skill. You have a skill, young smith-to-be. Maybe it will protect you.

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

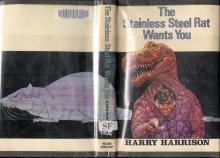

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

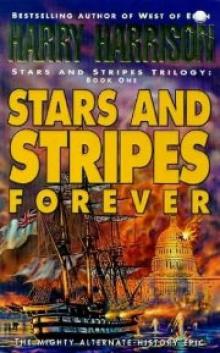

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

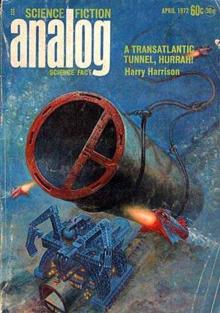

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

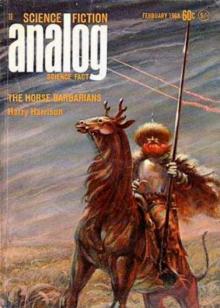

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

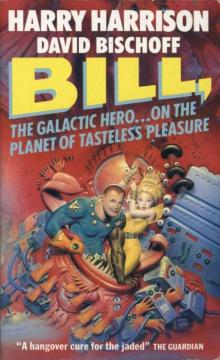

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures