- Home

- Harry Harrison

The Military Megapack Page 22

The Military Megapack Read online

Page 22

“Bullring?” asked Major Jimenez.

“Ay—La Plaza del Toros,” grinned the Moor. “And it will take many monkeys to sand it after this day’s spectacle. Look at them!”

And he ran back to catch up with his fellows, leaving Juan Jimenez to stand and stare.

And then, somewhere in the dust which came up from the column, a voice cried: “Juan! Juan!”

An insane face broke from the grey of the procession and he felt iron hard hands around his neck and a fever burned, parched mouth was kissing him.

And he looked down at the face of his mother.

Her hair, like coiled snakes, fell in wild disorder over her head and shoulders, down upon her half naked body. There was dried, matted blood on her dress and her hands were burned from holding a rifle. And she kissed him, and crooned over him in a cracked, broken voice.

“Juan—Juan. My baby!”

And then, as if for the first time, she saw his uniform, and hate and rage filled her eyes and she pushed him away with the flat of her hands, recoiled from him.

Then he saw his father. Dragging feet, bowed head, making furrows in the dust, as if great weights were attached to his feet. Face too dead to be alive. Set in deep lines. A cruel gash across the flesh of his chest.

And Juan Jimenez in his major’s uniform walked along the line with the procession of prisoners, and he heard hoarse voices cursing him.

And the dust got into his nostrils and strangled him, and he marched up and down the hills.

“But why do you fight like this?” he demanded of his father. “What is there to dying that is so holy? What is this thing you fight for? Don’t you know—you are fighting against Spain—your own land?”

And the old man’s eyes glinted for a moment behind the grey mask of the dust, and he said: “You could not understand. We fight for the land. We are Spain. Our sweat, our blood, our bodies, are Spain. We toil—it is right that we live for our toil, that we own the land. It is ours. It was given to us. We will never give it back. There will be no Spain without us.”

Juan fell silent, groping to understand. But all he had been taught so painfully, by Don Jaime, was a wall which his groping mind could not pierce.

And the father said, dully, like a whisper: “Go back—you have nothing to do with us. You are a soldier—you are a ‘gentleman.’ You are a friend of the Foreign Legion criminals, of the Moors! You cannot feel the people and the land. The boots on your feet have drained the land out of your blood!”

“Faster! Faster!” barked the Moors. Here and there they prodded a stumbling figure with the bayonet.

They came over the last hill. Into Badajoz.

“Where are my brothers?” asked Juan Jimenez.

The croaking voice of the mother sounded. Her face was expressionless. “Dead,” she said. “All dead—fighting. Go look at them, Juan. They are lying in the field in back of the house where the rifle pits were dug—where the bombs were dropped.”

“And the girls—Dolores and Inez?”

“Dead. There is no difference between girls and boys now. They are the same—they die the same—they hate the same—they kill the same. You will find them—lying in the same place.”

There was a little shuddering sigh from the head of the column. Below at the foot of the hill, surrounded by its trees, rose the whitewashed wall of the bullring of Badajoz.

In other days during the fiesta, the bulls came by this road, the black, sharp-horned fighting bulls, with glossy coats beautifully groomed. Going down the little hill to the bullring, to make a holiday for the people of Badajoz.

And now the long line, shuffling in the dust, stood and looked down at the bullring, and a strange animal-like cry, almost like the lowing of the bulls broke from the men.

The Moors, the only men in uniform, moved along the line, prodded bodies with bayonets and rifle butts, grinned, forced the column to move. Until the head of the column went into the bullring. The hundreds of them. Until Juan Jimenez said goodbye to his parents, under the main arch of entrance, and saw them driven into the space.

An hour passed and he was in the field tent, standing stiff, white-faced.

General Molo said: “Major Jimenez, I cannot understand your interest in these people. It is dangerous, frankly. It does not become an officer of field rank to show such interest in a mob of ruffians and cutthroats.”

Juan Jimenez’ voice sounded in his ears as if it spoke from a great distance. “Perhaps, Excellency, it is because the two in whom I am most interested are my father and mother!”

General Molo stared. “Your father—and—” he said slowly. His face was suddenly dark. “Soldiers have no fathers and mothers at a time like this, Major Jimenez. Bloodlines have been wiped out. This is civil war—brother against brother if necessary—to the last man, to the bitter end.”

“Because we have guns and money and can kill—are we saving Spain—by murdering Spaniards?” Juan asked dully.

Molo’s face was suddenly black with anger. “You are overwrought, lad,” he said, with a forced kindness.

“So—” said Jimenez hesitantly.

“I ordered a full investigation, Major,” nodded the general. “What I learned—is better spared. It is a blessing that the sons and daughters of your family died fighting. Beyond question, they were the leaders here. They were the core of the whole resistance in this countryside. Your sister—the one called Inez—was the infamous ‘Red Flame.’ She fought and led more fiercely than any of the men. I am sorry—it has all been established—by the prisoners themselves. They are proud of your sisters and your brothers—proud of the part they had in murder and bloodshed. It grieves me that the father and mother of a brave officer, a comrade-in-arms must die, but there can be no exceptions—no favors.”

“Thank you, sir,” said Juan Jimenez in the same dull voice.

He saluted, turned like a soldier, marched out of the room. The general’s face twitched as he watched him go. Then he went back to work on the papers on his desk.

* * * *

Juan Jimenez walked down the hill, to Badajoz, and came to the barbed wire before the bullring. The Moor sentry saluted and looked at him curiously as he passed.

Inside, three or four hundred people crouched miserably in the dust, red-eyed, starving, dying of thirst. Here and there one of them lay on the ground—dead. Juan Jimenez searched for his father and mother until he found them.

They were gathered together by the side of the ring. They sat on the ground, side by side. Their dead eyes were staring at the tiers of seats and at the machine-guns which were set up on those banks of seats—muzzles pointing toward the arena.

And Juan’s voice said: “I am here.”

Suddenly there was a hunger in his heart. A hunger for that earthen floor and those rocky, rolling hills which were watered by the sweat of all the Jimenez who had labored over them. There was a hunger to feel the sun on his naked back.

And a voice said in his brain: “Why do you wear that fine coat? You are a part of the land. You were born to it. These are your people. This is your place! Can you walk out of here, and leave them—look on them and fight down the cry of the blood in your veins?”

And he stood staring at the seamed, pitted faces of his parents.

With a great sob ripping at his throat, he turned and fled. Ran, like a mad, tormented thing, until once more he stood outside the bullring, and his heart beat like the tumult of a gun within his chest, and the sweat of agony slid down his pale, dust-caked face.

And a hand touched his arm, and a voice said to him: “Juan—Juan Jimenez—you are here!”

And he whirled and his mouth fell open and he stared into the face of Isabella de Cordova y Badajoz.

Her face was soiled with grime, but her eyes were soft and wet with tears of gladness. She looked at his uniform and swallowed a lump in her throat. Her voice, like the deep note of a bell gone husky, said his name over and over again.

Silently he gathered her in his arm

s and crushed his mouth against her lips, and she closed her eyes and clung to him.

“You!” he marveled. “They told me—you had died—with your father!”

Her eyes flashed fire then, and bold defiance. “No. I fled from them—hid in the cellar—with the dogs, Juan! You hear—with the dogs—in terror—like an animal—while they hunted me—”

All the fierce pride of her flamed out in that moment, and he was touched with a deep pity that she had been so humbled. Her face was ravaged and torment was indelibly burned into the dark of her eyes.

She shuddered and buried her face against his breast, and her body trembled and shook with her sobs. “But you came, Juan—the Legion came—and saved me—and now—” Her eyes roved to the huddled, broken mob, crouched in the hot, dry sand of the arena. “And now—” she said, again. The spark of revenge lit her face with a flickering flame.

“Hush, Isabella,” he said in a voice that cracked. “They are my people—are you forgetting that?”

She shook her head. “No, Juan. They are your people no longer. You have come too far to retrace your steps. See, you are a major now, an officer—glory lies ahead of you—you have become my father’s son—everything he hoped and prayed that you would be. You can never stand by their side again, Juan—never in this world!”

And with those words—words that his mind, his ambition, his intellect, told him were sane and true—a deep knell of isolation tolled within him.

“Never stand by their side—never in this world—”

The words sounded in his head, again and over again. A chorus of voices took up the strain, sent it hurtling back and forth in his brain, vibrant and repetitious as a long-living echo.

There was a little moan from inside the building. People stirred, stared, up toward the seats. The machine-gun crews were crouching, white teeth showing through grin-split lips.

A young girl in the middle of the throng leaped upon the barricade, ripped a great swatch of tattered cloth from her dress, swung it over her head like a banner and like a flag of battle. Her mouth opened wide, she screamed:

“Viva Espana! Viva el libertad!” A cry of defiance, of unconquerable determination and courage.

And within Juan Jimenez the tormenting echo answered: “Never—never in this world.”

Juan seemed to wake from a dream—a dream that had begun on a morning when he was ten years old and a fierce proud gentleman on an Arab steed had looked down at him and promised him great things. The dream was fashioned of those great things, unfolding with wraithlike magnificence, clothing him with glory—a false glory that fit him ill, that wore thin like worthless cloth and fell from him now, leaving him naked. Juan Jimenez, the son of a peasant and the grandson of a peasant.

* * * *

The dream had passed—and Isabella was part of that dream. Gently he disengaged himself from her arms and slowly, like one who is learning to walk anew, he marched toward the entrance of the ring.

“Juan—where are you going?” Isabella’s voice cried after him.

He did not look back, but she ran to him and seized his arm, his sleeve, his hand, pressing it feverishly to her heart.

“Juan—answer me—where are you going?”

He looked down at her, almost pityingly. She would never understand—never in this world. “To them,” he said. “To be with them—by their side—in their midst—now.”

Her eyes stared at him as if he were mad. “You would leave me—leave this”—her fingers flicked the chevrons on his sleeve—“leave everything—for what? For nothing—for less than nothing?”

“Yes,” he said. His jaw set stubbornly. “I see what is right. I see what must be.”

“You are a fool, Juan Jimenez—a fool!” Her voice was shrill—the bell had cracked. Dark hair tumbled over her glaring eyes. Red lips parted in a sneer. “Peasant—clod—fool!” she shrieked.

Wearily, patiently, Juan pushed her away from him, sustained by the conviction within him. The end of doubting had come. The uncertainty was finished. The knowledge of what he was filled his heart, and steadied him.

The huddled people were standing now. He pressed through them, groping quickly toward his mother and father for there was so little time. Then he found them, standing, hand in hand, their eyes looking at him dully. For they could not understand, either. Over and over they shouted in cracked, hoarse, splintery voices:

“Viva Espana! Viva el libertad!”

And suddenly Juan Jimenez heard his own voice screaming with them—felt the muscles of his throat grow taut with the force of that anguished scream.

There was the sudden chattering of a machine-gun, and then a dozen machine-guns, and people on the floor of that arena quivered and shook as they stood and screamed, slumped to the ground, still screaming.

The girl who waved her skirt like a battle flag slumped and fell, and the machine-guns chattered on and on while blood spattered the barricade walls, and the little mounds of dead and dying piled up.

Something struck Juan Jimenez through the belt of his major’s uniform, and ripped through his stomach, and then a quick succession of sharp pains stabbed through his body and he felt his legs buckling under him. A queer, rioting glory filled him.

The last thing he saw was the face of a grinning Moor squinting over the sight of a machine-gun. The last thing he heard was the echoing cry:

“Viva el libertad!”

The sun glinted on his glazing eyes, and blazed down hotly on all the rocky hills of Badajoz.

THE BLOCKADE RUNNERS, by Jules Verne

Chapter I

THE DOLPHIN

The Clyde was the first river whose waters were lashed into foam by a steam-boat. It was in 1812 when the steamer called the Comet ran between Glasgow and Greenock, at the speed of six miles an hour. Since that time more than a million of steamers or packet-boats have plied this Scotch river, and the inhabitants of Glasgow must be as familiar as any people with the wonders of steam navigation.

However, on the 3rd of December, 1862, an immense crowd, composed of shipowners, merchants, manufacturers, workmen, sailors, women, and children, thronged the muddy streets of Glasgow, all going in the direction of Kelvin Dock, the large shipbuilding premises belonging to Messrs. Tod & MacGregor. This last name especially proves that the descendants of the famous Highlanders have become manufacturers, and that they have made workmen of all the vassals of the old clan chieftains.

Kelvin Dock is situated a few minutes’ walk from the town, on the right bank of the Clyde. Soon the immense timber-yards were thronged with spectators; not a part of the quay, not a wall of the wharf, not a factory roof showed an unoccupied place; the river itself was covered with craft of all descriptions, and the heights of Govan, on the left bank, swarmed with spectators.

There was, however, nothing extraordinary in the event about to take place; it was nothing but the launching of a ship, and this was an everyday affair with the people of Glasgow. Had the Dolphin, then—for that was the name of the ship built by Messrs. Tod & MacGregor—some special peculiarity? To tell the truth, it had none.

It was a large ship, about 1,500 tons, in which everything combined to obtain superior speed. Her engines, of 500 horse-power, were from the workshops of Lancefield Forge; they worked two screws, one on either side the stern-post, completely independent of each other. As for the depth of water the Dolphin would draw, it must be very inconsiderable; connoisseurs were not deceived, and they concluded rightly that this ship was destined for shallow straits. But all these particulars could not in any way justify the eagerness of the people: taken altogether, the Dolphin was nothing more or less than an ordinary ship. Would her launching present some mechanical difficulty to be overcome? Not any more than usual. The Clyde had received many a ship of heavier tonnage, and the launching of the Dolphin would take place in the usual manner.

In fact, when the water was calm, the moment the ebb-tide set in, the workmen began to operate. Their mallets kept perfect time falling

on the wedges meant to raise the ship’s keel: soon a shudder ran through the whole of her massive structure; although she had only been slightly raised, one could see that she shook, and then gradually began to glide down the well greased wedges, and in a few moments she plunged into the Clyde. Her stern struck the muddy bed of the river, then she raised herself on the top of a gigantic wave, and, carried forward by her start, would have been dashed against the quay of the Govan timber-yards, if her anchors had not restrained her.

The launch had been perfectly successful, the Dolphin swayed quietly on the waters of the Clyde, all the spectators clapped their hands when she took possession of her natural element, and loud hurrahs arose from either bank.

But wherefore these cries and this applause? Undoubtedly the most eager of the spectators would have been at a loss to explain the reason of his enthusiasm. What was the cause, then, of the lively interest excited by this ship? Simply the mystery which shrouded her destination; it was not known to what kind of commerce she was to be appropriated, and in questioning different groups the diversity of opinion on this important subject was indeed astonishing.

However, the best informed, at least those who pretended to be so, agreed in saying that the steamer was going to take part in the terrible war which was then ravaging the United States of America, but more than this they did not know, and whether the Dolphin was a privateer, a transport ship, or an addition to the Federal marine was what no one could tell.

“Hurrah!” cried one, affirming that the Dolphin had been built for the Southern States.

“Hip! hip! hip!” cried another, swearing that never had a faster boat crossed to the American coasts.

Thus its destination was unknown, and in order to obtain any reliable information one must be an intimate friend, or, at any rate, an acquaintance of Vincent Playfair & Co., of Glasgow.

A rich, powerful, intelligent house of business was that of Vincent Playfair & Co., in a social sense, an old and honourable family, descended from those tobacco lords who built the finest quarters of the town. These clever merchants, by an act of the Union, had founded the first Glasgow warehouse for dealing in tobacco from Virginia and Maryland. Immense fortunes were realised; mills and foundries sprang up in all parts, and in a few years the prosperity of the city attained its height.

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

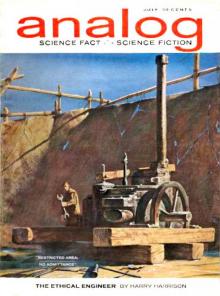

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

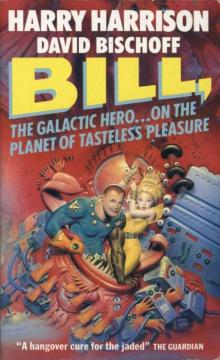

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures