- Home

- Harry Harrison

The Military Megapack Page 21

The Military Megapack Read online

Page 21

Jimenez nodded and took the map in his hands. “I understand, Excellency,” he said alertly. “I shall do everything possible.”

The general put a hand on his shoulder. “I know you will, lad,” he told him with a paternal pat. “You will take your three machines again—and again—until we have won. Good luck, my son.”

And Captain Jimenez climbed up to his high perch in the forward cockpit of the Caproni. Behind him his gunners were in their seats, helmeted and goggled, guns unslung. The bomber was in his tiny booth, fussing with his sights. The motor ticked over. Further downfield stood two other Capronis readied for flight.

Jimenez moved the controls, tested his motors. After a moment he lifted his hand in the signal, and poured the throttle to the powerful monoplane. It roared forward, skimmed over the earth, grew lighter, lifted its tremendous bulk, lunged upward into space.

Juan Jimenez sat there, his hands handling the controls delicately. Except his helmet and goggles, he wore no flying equipment. His uniform was the uniform of the Spanish Foreign Legion. His face was black with the North African sun. His little black mustache was trim and crisp, his fierce black eyes looked over the horizon of the world. His mouth was hard and firm.

Many things had happened to Juan Jimenez since the day of the miracle. There had been the great house of Cordova, and the new clothes, and the interest of Don Jaime in the career and progress of his protégé. And there were times when Don Jaime had looked at this straight-backed, fiery-eyed lad with a soft light in his proud old eyes, for Don Jaime had no son of his own.

But Don Jaime had a daughter and her face was soft and dusky. Her body was like the white statues surrounding the fountain, and her voice was like the deep note of a bell. Don Jaime frowned at first when the two children played and laughed together, for it was not good that a daughter of the house of Cordova should be so intimate with the son of a serf-peasant. But when Juan Jimenez had blossomed into the appearance and mannerisms and speech of a gentleman, Don Jaime did not scowl. Instead he wondered what kind of children would be born to this daughter from a strong husband, like this boy, Juan.

The officers of Don Jaime’s staff instructed Juan as a soldier. He wore his uniform and he carried his sword and he commanded Don Jaime’s soldiers under the watchful eyes of the officers.

And when he was fifteen he went to military school, and spent four years—hard, grinding, toil-filled years. Then he graduated as an officer, and wore the uniform of his regiment. He came home after that schooling. His father and mother stared at him as he dismounted. And it seemed that his mother was on the verge of bowing her head. His brothers and sisters stood in silence and stared dumbly.

Somehow Juan Jimenez felt that he had come back to a place peopled with ghosts—had come back to the living dead. The house seemed more wretched, more mean, than ever. And Juan Jimenez heard the envying whispers of the villagers and they burned within him. He saw the bare feet and the lined, parched faces, and the red-rimmed eyes, and he saw how the shoulders of even the young women sagged, and how their bodies were old when they were yet young, and heard how the babies cried, and saw the faces of the men—the men who had never been over the hill—and who did not know that a world existed beyond Badajoz. Ragged, almost naked, clinging desperately to barren, worn-out land, hacking at it with poor tools, burning with the sun, shivering with the chill.

He looked at his own hands, soft, white, shapely. This mud hut seemed like a dream. He thought of Isabella de Cordova y Badajoz, her proud beauty, her sweet, trembling kiss. He had blushed even while his heart surged within him. Now he blushed, too; his loneliness was like a sickness deep in his heart.

And a voice whispered within him. “These are your people. These hills, these stony ridges—they are yours. This sun which beats down on their heads is the same sun which shines on your uniform. You are born of their toil.”

Then he rode back over the hill toward Badajoz with a strange unrest, a strange hunger and that strange pain in his heart. And it seemed that wraithlike invisible hands were trying to pull him down from the white horse—drag him back to the earth.

Then Juan Jimenez fixed his eyes on the heavens, and again went back to school. After a year he became an aviadore, a military pilot, with wings on his tunic. He flew. He drove planes into the far heights and looked down on the world, and sometimes he smiled as he flew, wondering what that mother and father would do and say if they could see him.

* * * *

When King Alfonso fled from his throne, Jimenez was in Africa, fighting against the wild tribes which were in constant revolt against Spain. He heard rumblings of “the people.” Government by the people. No more kings. No more dons. No more grandees. The land was to belong to the peasants.

In Africa there was no such talk about government. The Army was in Africa. The fierce, bustling Legion. And the Legion was recruited to greater and greater strength and greater and greater quantities of war material were dumped down in Spanish African ports and stored carefully.

The Moors were uniformed and trained, given new knives and new rifles and shoes. The Moors, for five centuries the blood foes of the Spaniards. Deadly, vicious fighters.

And Lieutenant Jimenez became Captain Jimenez and wore decorations on his tunic. His fellow officers said of him, enviously, half in admiration:

“He will be a major before he is thirty, that one, and a colonel before he is forty. And he will certainly be a general.”

Then the Foreign Legion started to move. The Capronis were landed on the African sands, twenty or more of them, and for days, Juan Jimenez and his fellow pilots shuttled back and forth across the sea, the ships laden with soldiers—the Foreign Legion and the Moors.

Trip after trip, putting the Foreign Legion ashore in Spain. Grim eyes, heavy-handed troops, merciless because the country in which they fought knew no mercy to victor or vanquished. Hardened to the sight of death and suffering because they had lived day by day with death, disease and destruction. Men who killed the wounded as a matter of course because it was more humane to kill them than to permit them to die, festering under a hot sun, when no medical or surgical attention was possible.

* * * *

Guns, tanks, artillery, moving across the sea, expertly, rapidly—to Spain. To fight against Spaniards. To fight against peasants and workers, those who dared to defy authority by right of birth.

Madrid, with the Capronis flying overhead, and the bombs crashing in the streets, and the fronts of whole houses blown to a shambles by the low flying, racing bombers. With blood spattering the paving stones and spurting into the air. With crowds of people cowering, running to cover—Spanish people. Day after day, night after night, dropping bombs on Madrid.

While on the ground, the Legion marched over Spain. And the Moors, grinning, those wicked knives unsheathed and those naked bayonets gleaming, stormed into village after village.

There were times when Juan Jimenez closed his eyes, and was sick. How the Moors loved those mass executions—lining fifty or a hundred people in a long line, and killing them all with one burst of machine-gun fire, laughing as they killed. Spaniards dying—at the hands of Spaniards. A war of extermination on both sides. When a position was taken, no defender remained alive.

Day after day, long lines of prisoners marching in the dust of the roads, herded along by the grinning Moors. Men, ragged, dull eyes, drooling at the mouth. Some of them dying as they marched, from shocking wounds which no one had time to bind. Women carrying infants, children, whimpering, clinging to the sodden skirts of mothers. All of them—going over a hill—and then the sound of machine-guns, and screams, and the smell of blood in the air.

All because they loved the land. All because they clung fiercely to the land. All because they would not give up the land. That poor, exhausted, barren soil of Spain.

Leathery-faced, bleary-eyed peasants, plodding with blank faces, knowing they were going to death, and going grimly, silently and stolidly. With Spaniards standing by,

faces inflamed with hate and rage, and giving the orders which killed these peasants by the hundreds.

Sometimes Juan Jimenez closed his eyes after a sharp breath. A face—so like his father’s face it made him stare. A body like the worn, twisted body of his mother as he had last seen her—going along the road, eyes straight ahead.

And a shudder shook him, and he turned away sick. Why couldn’t they see as he saw—as Don Jaime had taught him to see? Why did they let themselves be mowed down like cattle, like dumb mindless cattle?

Along the roads, bodies—the dead—everywhere. Young men, dead, sprawled out in the grass, looking with dead eyes up at the sun, the blood still running from their wounds.

And more and more marching columns, going to the machine-guns. Until the whole land seemed filled with the sick-sweet smell of decaying bodies and festering blood.

A thousand feet over Irun, Captain Juan Jimenez looked down on the heights of La Puntza. There was a thin, ragged series of rifle pits on the top of the hill. The summit was wreathed by the flashing of exploding shells and drifting smoke. Crews crouched about machine-guns, and the gun spat and chattered at moving bodies going doggedly up the hill, rushing from rock to rock, bodies, with the sun glinting from steel helmets, men of the Legion, fearless, pushing on over the bodies of their dead, charging up into the face of those searing, deadly blasts from machine-gun muzzles.

On top of the hill a ragged army of workers—Loyalists. White shirts, ragged trousers, bare feet, clutching rifles, crouching down in the pits, with a withering rifle fire crashing out of the trenches. Women with them, understanding the great need of defense, firing beside the men.

And the shells from the batteries on the plane below bursting wickedly among them, catching them up, breaking them to bits, smashing them to quivering masses of bloody pulp. Shell bursts, racing along that line of entrenchment like a grass fire, scorching, burning, blasting. The dead tumbled about, arms flung out, mouths open.

For days this had been going on. The battle for Irun and the sea. Reckless, insane killing. No mercy on the top of that hill, no mercy on its flanks. Irun a blasted, ruined heap of wreckage, burning so fiercely that the glare of the flames could be seen from twenty miles away at night.

In the streets, gaunt-faced men and women, chained to the front of buildings like captured animals. They were the Rebel prisoners the Loyalists had threatened to chain in the line of artillery fire if the attack on Irun was not abandoned. Five or six hundred of them. Some half buried under fallen façades.

All of them Spaniards, being killed by Spaniards.

* * * *

The three Capronis droned in over the defenses on the top of La Puntza. The white-shirted fighters on the top of the hill shook fists and rifles in impotent rage. They fired at the bombers. Machine-guns were uplifted, made a foolish attempt to blast down the Capronis.

Three bombs fell out of the belly of Captain Jimenez’ ship. He watched them drop, slanting. There was a smear of flame from the top of the hill. Rock lifted a hundred feet in the air. The hilltop shook and shuddered with the violence of the explosion. Bodies whirled around crazily like scraps of paper in the wind.

Other bombs fell on top of the hill. The whole area was riven, broken, pulverized. Out of the hell, ragged men and women, with streaming hair and screaming voices, fled the destruction which murdered them. Fled down the hillside toward Irun.

The shining helmets of the Legion were dotting the hillside, going up with a rush, yelling, and the bayonets were at work among the defenders. They were like tigers. They fell among the shock-sodden defenders. The blades of the bayonets no longer glinted, but they were dulled with the red of Spanish blood. The remnant of the attacking battalion of the Legion stood and cheered, and then went on with the business of death.

From Irun the Loyalist guns opened on La Puntza. New shell concussions rocked the heights. Death struck among the victors. A ragged line of irregular troops swept up the hill.

Fear, panic swept through the town. The way to France was choked with refugees, swarming, carting impossible bits of personal property.

The Rebel guns opened on the road, blew great chunks out of that long line of slowly moving people.

The three Capronis came in over the town. The bombs fell. The houses were seized with convulsions. The men and women, chained in the streets were blown to bits. That was war, one could not hazard the victory for a few hostages.

Bombs in the road—blasting great craters in space which had a moment before been choked with fear-maddened people.

* * * *

One of the Capronis suddenly staggered, weaved about in space. There was a gash in its right wing. The wreckage of its right wing motor hung down grotesquely, seemed suspended on a string. It went down in ugly circles. The gunners were standing up in seats, staring over the side of the ship.

Suddenly one of them jumped. His parachute opened a hundred feet below the ship. He floated about.

And on the ground, the milling people forgot to run, forgot to be afraid. They circled around under that falling parachute, they chased it back and forth, their faces turned upward like a white blur. Trotted this way and that with the vagaries of the wind which moved the chute. Their arms were outstretched, hands like claws.

The gunner drew his pistol. He fired down at the faces under him. Then he touched earth—and the mob was upon him, hiding him from sight—working with hands and feet and teeth. Crushed and stamped and ripped at the body of that gunner. Tore the chute to shreds.

The big Caproni smeared into the earth, broke its back. The second machine-gunner did not jump. He stayed in his cockpit, held in by his belt. The fuselage of the ship slanted at a crazy angle. The mob charged the ship. He stood up in his seat, brought his gun to bear, fired, coldly, implacably, mowed them down, killed three and four at a time with the same bullet in that crazy press of human bodies.

Then the mob swept over the ship, rent it with their hands—and the pilot, the bomber and the machine-gunner disappeared in the swirl of hate and blood-lust.

The ship was reduced to splinters.

And Captain Jimenez turned his head away, a leaden weight of sickness in his belly. Spaniards rending Spaniards.

“That was a splendid piece of bombing,” a voice seemed to be whispering. “Just the lift we needed to clear La Puntza. Tonight our men will be in Irun—and then—we will teach them to chain men in the streets like dogs! Heaven help anyone the Legion finds in Irun this night. All day the Legion had been walking over the bodies of its own dead. The Legion will not leave a stone standing in the city—nor a Red alive.”

Then another voice cried out within him. “But Irun is Spanish! The Legion is Spanish. The people we are killing and who are killing us—are Spanish.”

Then he was down on the ground, legs dead and belly sick. His major was standing beside him, applauding what he had done, laughing jovially. “Tomorrow we leave this hell hole,” the major said. “We go to Badajoz—to another hell hole. They are fierce there—”

The word smashed upon Juan Jimenez’ brain like a shrapnel shell.

“Badajoz?” he asked strangely.

“Surely! Ah, I forgot. You are from Badajoz. A nest of traitors. The most stubborn, bloody-handed, murdering blackguards in the whole of Spain. We must crush them—wipe them out!”

CHAPTER III

End of Flight

There is was. The House of Cordova, like the bones of a cow that had died of starvation and been burned. Blackened embers, and a nasty hole in the ground. Down there somewhere was a bloodstain against the wall where the peasants of Badajoz had executed Don Jaime de Cordova y Badajoz.

There were the hills over which Juan Jimenez had trudged the miles between his father’s mud hut and Great House. Those rolling, rocky, plow-scarred hillsides, in ruins, without even the meager crops of yesterday. With the smoke rolling up from a dozen villages and with the bodies of the unburied dead lying in the streets.

The Capronis soared ov

erhead, dropped the deadly bombs and the mud huts flew into spurts of dust. Along the road there were rifle pits, and craters formed by exploding shells. The bombs were raining down and the scream and blare of airplane engines filled the heights.

Gushing, flaming death, falling on the crooked backs of the peasants. Death which killed them in droves, and against which they could not fight.

The steel-helmeted troops, charging fiercely stormed into position after position. Stormed through the streets of that little village in which Juan Jimenez had been born. Rifles spat defiance, even as the bombs fell and blew the defenders into oblivion.

Smoke drifted and rolled, and the moving wall of flame consumed the village and behind the fire came the steel helmets of the Rebel troops. And the peasants fought from behind breastworks formed by piling up the bodies of their neighbors and children. The bodies of their own dead, and struck, and struck, and struggled until they were cut down, or pierced with bayonets.

All day the prisoners marched toward Badajoz. The dust in the road was churned by their bare feet. The sweat ran down their naked backs. They marched with vacant eyes and grey faces. Up the hill, down the hill, over the next hill.

Juan Jimenez in his new major’s uniform and his new decoration stood on the top of a little hill and stared. For La Puntza, Juan Jimenez had been decorated. For the reduction of the Loyalist lines north of Badajoz he had been made major.

Those dead eyes looking at him—eyes of the prisoners marching by. Now and then a man or a woman in that line turned face and spat at him. Now and then a wild-eyed, sobbing young girl would scream out curses at him.

All day long he stood there and watched them herded by like cattle. Once Juan Jimenez had stopped a Moorish non-com and had said: “Where are you taking these people?”

And the Moor had stared almost insolently, and he had answered: “To the bullring, Excellency—where else?”

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

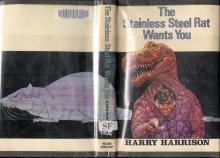

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

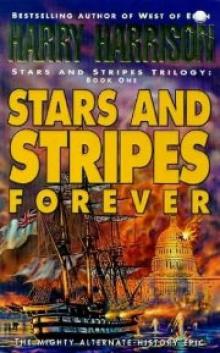

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

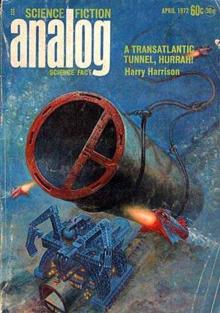

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

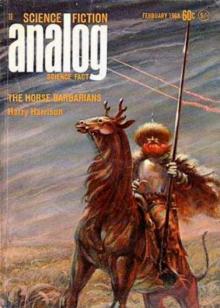

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

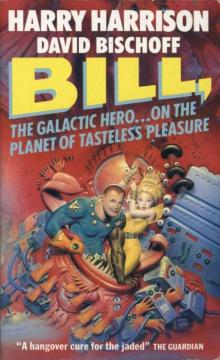

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures