- Home

- Harry Harrison

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Page 9

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Read online

Page 9

Daylight was streaming through the high windows now, lighting up the building’s interior. Dark and shabby. The only touch of color coming from some badly framed painting of figures burning in leaping fires. Repulsive.

We followed our stumbling guide up a flight of stone stairs and through a gilt-framed doorway. The large room beyond was lit by stained-glass windows depicting more scenes of diabolic torture. I did not have a chance to look at them because my attention was drawn at once to the black-clad man seated on a heavy chair before me. I had been right: black was the new black.

I had been even luckier with the skull-and-crossbones cap design, for he was wearing a large silver skull on a chain about his neck.

“I have never heard of you or your organization,” he said. Words dripping with venom.

“That is because you are on this backward and forgotten planet. Your name?”

He was silent for long moments, glaring at me, his hands gripping tight on the arms of the chair. Then, reluctantly.

“I am Father Coagula, prime rector of the Church of the . . .”

“Then you are the one I am here to see. We have had grave complaints about your church.”

He wasn’t getting up and I wasn’t going to stand before him like a penitent. There were chairs against the wall: I caught Angelina’s eye and pointed towards them. She nodded grimly back and brought one over.

“Females are not permitted in this chamber,” he hissed.

“They are now. Where I go Sister Angelina goes.”

I sat and matched him stare for icy stare. He blinked first.

“What do you want here?”

“I told you—we have had complaints.” I took out a black-covered notebook, thumbed through it, then read . . .

“You have attempted to subvert another religion, namely that of the Children of Nature and Love, with whom you share this planet.”

“They are idolaters and worship a false god. We simply showed them the Way—”

“You oppressed them, drove them from their homes and now cheat them of their rightful gain.”

“What are you saying?”

Was there a touch of defensiveness in his voice? Naturally he would cheat the Children out of the true worth of the flowers they traded for.

“We have had complaints from those to whom you sell the perfume.”

“They lie!”

“They speak only the truth. Our agents have talked to them. Other skilled agents have penetrated your ranks and found the secrets of your stills that are used to make the perfume you trade.”

Coagula leaned back as though struck a physical blow. “You can’t—”

“We can . . . and we will. Distillation is a well-known process on all civilized worlds. We will disclose every secret of the perfume process to the Children of Nature and Love. Then give them the materials to construct the stills. These are the people you have so viciously cheated. Unless you agree to our terms.”

“What . . . are they?”

I tapped my notebook. “They are written here. Bring in your scribes to write them down as I read them out to you.”

He was slumping now, defeated in every way. After a moment he seized the bell hanging from the arm of his chair and rang it.

“You are being wise. I will order my troops to stand down.”

Then I added, in the same bored voice. “We will use your communication facilities to contact our ship.”

He looked up and shook his head.

“But . . . we have none.”

“Do not test my temper,” I roared at him. “We know that you contact the traders when you have perfume to sell.”

“But . . . we do not. They come whenever they want to. They have refused to give us communication apparatus. They did not want us contacting others of their trade.”

Zero. Nothing. The best-laid plans . . . I drew myself up and salvaged what I could from the ruins.

“It matters not.” Angrily. “Where is your scribe?”

“He comes.” He shouted instructions at the priest who had answered his bell.

Depressed, I pondered the future.

We must leave Floradora.

But . . . where would we go?

I HAD TO PLAY OUT this farce to the very end. Dictating the terms of agreement that, in the future, payments for the flowers would be doubled. The Vengefulers also agreed that no future attempts would be made to convert anyone to their sadistic religion. They could keep it to themselves. I made a silent oath—if and when we returned to civilization again—to report their presence to the Galactic Authorities. Let them ponder over responsibilities here. Of course they respected the rights of all religions to believe what they would. But how did they feel about children on this world growing up to a life of paranoia and superstition? I had heard rumors that there was a Psych Corps that aided and abetted the spread of reason: I can only hope the rumors were right. Copies of the agreement were made. Read, signed, witnessed, signed again. Father Coagula turned away and averted his eyes when we left.

Still depressed by the failure to open communication, I felt slightly better that we had at least brought some aid to our vegetarian friends.

Bilboa was waiting by the oxcarts. I gave him what I hoped was a cheerful thumbs-up. He looked surprised.

“Your hand gesture means that the food is very good—is that what you mean?”

“Sorry, to us it means things are going well.”

“In what manner?”

“The Vengefulers have signed an agreement for a happier future. First off they will stop any future attempts to convert anyone to their dismal religion.”

“I thank you, friend Jim.”

“You are welcome, friend Bilboa. They also agree to double their future payments for your flowers.”

“Oh joy and happiness! We can buy more medicines from them. There are some illnesses we cannot cure—now lives will be saved . . .”

Then he stopped—stepped back—and an expression of deep sorrow spread across his face.

“I beg your forgiveness, dear friend. I have wronged you, disparaged your people—and you are the one to turn the other cheek, as taught in holy scripture. I took such offense at your horrifying eating habits that I wronged you, the wise and generous man that you are.”

He reached out impulsively and took my hands in his. I felt more than a little embarrassed for there were tears in his eyes.

“Glad to help . . .” I muttered. “No big deal. Only fair thing to do.”

“Still, I cannot forget that I wronged you and your people. I humbly apologize. They and their fine beasts can stay here on Floradora—for are we not our brothers’ keepers? We already share our world with the loathsome city dwellers. Certainly there is room for everyone—far from us of course. And you and your shipmates must stay as well.”

This was indeed a morale builder. My spirits rose with the good news. Free at last of Elmo and his crew! Our future still wasn’t clear, but at least there would be no porcuswine and their keepers in it. I joined the others boarding the carts.

When I broke the news to Angelina and Stramm they were as excited as I was. As soon as we got within broadcast range of the ship I would tell the captain.

Elmo could wait—particularly since he was sound asleep, as were the others.

With very little effort I put my head down and did the same.

BACK AT THE SHIP IT was a grim and silent group that gathered on the bridge.

“I think we better discuss our future before we tell Elmo that they will be able to stay on Floradora.”

“Whatever we decide it will be a pleasure to have them off the ship,” the captain said.

“I go along with that!” Stramm added. “We can use water as reaction mass again.” He smiled at this blissful thought. Then frowned and dug a crumpled bit of paper from his pocket and read from it.

“I have been running the graviton collector ever since planetfall. As of today it has added two thousand and twenty-two units to the

tank.”

“Which means . . . ?” the captain asked.

“Forty-three more minutes of Bloat time.” He sighed. “You must remember that it is an old machine.” Only silence followed.

“At least the reaction mass tank is full—drinking water tanks as well. We can get into orbit as soon as you say.”

Angelina had the only encouraging news.

“While the elders were arguing about their future dealings with us carnivores, the women brought aboard loads of fresh cheese and produce.”

“Hurray for them!” I said brightly, trying to improve the mood of the day. “We’ve agreed among us that we will leave here after we unload the pigs and people.” Then I frowned. “I was forgetting that we had to move them and their repulsive gustatory habits away from the flower folk. We’ll put a call throughout the ship. Arrange for the conference to be held in the dining room.”

It took some time to stir Elmo and company awake and goad them to the meeting. Sensibly, the captain and engineer were prominent by their absence. Angelina sat chatting among the women—while I faced the bleary-eyed men.

“Gentlemen,” I said, starting off with a lie. “You will be pleased to hear that our little adventure was a complete success. The Vengefulers will venge no more and not bother the other kind folk on this planet—and that means you as well. Angelina and I, and the rest of the crew, must leave this fair world. But you—you lucky lot!—have been invited to make this your home. You can look ahead to a prosperous future—though I must admit you will have limited means of disposing of your excellent pork products—”

“That’s a real kind of a problem, Cousin Jim,” Elmo said, breaking in with newfound determination. “Without no income, why how we gonna live?”

“You can trade with the city,” I said, with a touch of desperation in my voice. Elmo gloomily shook his head.

“From what the locals tell us we best stay away from them.”

“And we got us other problems,” a burly swineherd called out. “The only television we got is from them city people and it’s no good at all.”

“All shooting and killing and praying and such and no soap operas,” a woman in the front row said, and the sisterhood nodded fiercely.

“But . . .” I said, and it was a pretty feeble but. Any arguments I produced could not sway them from the lost pleasures of TV. I looked at their determined features and had to admit defeat.

“Yes,” I said, fighting to hold back a heartfelt sigh. “You had better start bringing the animals aboard as soon as possible.”

I went to break the news to the crew. Who took it in stoic silence, bad news being the order of the day.

“I never liked this planet from the moment we arrived and were shot at,” Captain Singh said. “Let us get off-planet as soon as we can then plan our next Bloat jump.” He swung about in his chair to face the control board. “Let me know as soon as everyone and everything is aboard. Tell them we’ll pull a maximum of one-G during takeoff. Make sure all the livestock is secured. One of the sows broke a leg when we landed and I have had nothing but hassle from our passengers ever since.”

I went to say my good-byes to Bilboa and friends, which was a time-consuming process. Even then I found that the boarding was slow and tearful, with many good-byes. I went to the bridge where I joined the equally depressed captain, who was gloomily watching the slow preparations for departure.

“I checked and everyone’s aboard,” Angelina said happily as she joined us. “I’ll miss the nice people here.” The silence that followed was thunderous.

“Best go to our cabin now,” I said.

We went. Angelina gave me a quick hug before lying down on her acceleration couch. “You did everything possible, Jim. We were all so sure that those Vengefulers had interstellar communication. And the vegetarians should really thank you for the way you improved their dealings with those dreadful city people.”

This cheered me slightly, but I still had great fears for the future. “We should change the name of this ship.” I said as I buckled in. “Did you ever hear the old myth about the Flying Dutchman?”

“What’s a Dutchman.”

“I have no idea. But it was an ocean vessel of some kind that was supposed to be sailing under a curse. That meant that it could never reach port and was doomed to sail on forever.”

“How awful. But I’m sure that won’t happen to us.”

The buzzer rasped loudly and the recorded voice announced “Ten-second warning.”

Takeoff went well. At least something did for a change.

Angelina unbuckled and stood up. “I’m going to see how the porcuswine fared after this takeoff.”

“Right. I’ll be on the bridge.”

Captain and engineer were laboring at the computer; cabalistic equations ran down the screen. After much muttering they seemed to reach an agreement. The captain pushed his chair back and pointed to the screen.

“I’ve gone through the galactic ephemeris and this seems to be the optimum balance of all the factors.”

I nodded—although the spatial coordinates were just a meaningless series of numbers.

“I’ve balanced out favorable locations that could be reached in one Bloat, against stellar density. This is our best choice.”

“Do it!” I said. “Let’s see if our luck is better this time.”

“Beginning Bloat,” he said, hitting the RUN-PROGRAM button.

Floradora began to shrink slowly behind us, growing tinier and tinier until it blinked out of sight.

“The bar is open!” I said with false enthusiasm. Then I remembered that the captain never drank on duty—and Stramm was already on the way to the engine room.

Hopefully Angelina would share a cocktail with me. If not, I was sure Pinky and I could split a bowl of curry puffs . . .

THE DAYS CRAWLED BY. I saw little of Angelina, who was exacting a great deal of pleasure from her unexpected female companionship. I began to realize that women were far better than men at enjoying the company of one another. The thought of socializing with Elmo and friends—what could their conversation possibly consist of?—was a frightening one! I did extract some enjoyment—and a good workout—from helping Stramm strip down and reassemble one of the major thrust bearings on the landing jets. I still welcomed warmly the captain’s announcement over the ship’s speakers.

“Getting radio signals now . . . I’ll see if I can amplify them.”

I must say that the elapsed time between emergencies was getting shorter and shorter. I relaxed after we had finished work and had just made my first drink, was stirring the ice to chill it, when the wall speaker rustled and the captain spoke:

“Boss Jim to bridge.”

I sipped, then frowned. Had there been a touch of anxiety to his voice? Yes, there had. I put the drink down and headed for the stairs. He was frowning at the viewscreen when I came onto the bridge.

“Something is wrong?” I asked.

“There certainly is. Come look at this.”

This was a bright star slightly off-center on the screen. He pointed to a much-dimmer star in the center of the screen.

“This is the star system that is our target destination. The brighter star should not be there.”

“Which means . . . ?”

“I’ll tell you in a moment, as soon as the spectral analysis is complete—there it is.”

The computer pinged, the printer hummed, then ejected a printed sheet. He took it and scanned it quickly: the frown became a scowl.

“Helium, carbon, nitrogen and oxygen—in that order of quantity . . .”

“Which means?”

“Ejecta.”

“Explain if you please—physics was never my best subject.”

He touched a changing number low on the screen. “It is getting brighter and hotter the closer we get.” He was not happy with this. “What we are looking at is a star gone nova. If we stay on this course we’ll be a smoking cinder before long.”

“C

ut the power! Go back!”

“Impossible—as I have explained. We cannot retrace a Bloat course. What I can do is gradually reduce the power and shorten our Bloat time. But we can’t activate a new course until the Bloat is over.”

“We’ll be toast . . .”

“I hope not.”

I was still not sure what was happening. And what was the nova star doing there?

“Wasn’t this nova in the stellar ephemeris when you plotted our course?”

“Obviously not.” He groped in the drawer for his glasses; it was obviously lecture time again. He put them on and we were back in the classroom. “Although stellar surveys are being made constantly, it is a big galaxy out there and this nova was obviously not at this location when the last survey was made.”

“But a star doesn’t go nova just like that.”

“Normally, I agree. But there are exceptions. Some novae are recurrent, albeit on a time scale ranging from a thousand to a hundred thousand years. The recurrence interval for a nova is less dependent on the white dwarf’s accretion rate than its mass . . .”

The lecture ran its course but I tuned out. The only thing that mattered was how hot it would be when we popped back into normal space. I cracked my knuckles and brooded until the lecture mode ground to a halt. Only when the captain took off his glasses did I venture to ask a question.

“Do you know how hot it will be when this Bloat ends?”

“No. I can measure it, but of course we won’t be able to feel it until the Bloat terminates.”

“Why?”

“Because of the attenuation of our molecules during Bloat, all the wavelengths apparently change. Only when we have resumed our normal dimensions will the temperature change be felt.”

“Which will be when?”

He looked at the control panel. “I’m shortening the Bloat time steadily. As of now we have five hours to termination. But there will be updates.”

I looked at my watch—then set the alarm. “I’ll be here again in a few hours.”

I made my way slowly back to the bar and my tepid drink. Angelina came in just when I was making up a shaker of refills.

“Someone is looking very glum,” she said.

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

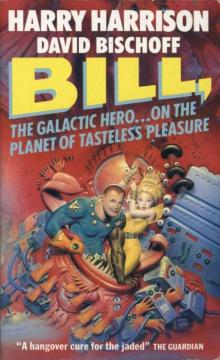

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures