- Home

- Harry Harrison

Lifeboat Page 9

Lifeboat Read online

Page 9

Why? That was the question. Why was the Captain being so adamant in her refusal to do the sensible thing and head for the nearest safe planetfall? Maybe if he could find out what was motivating her....

7

Two sleep-days later, Giles still was without an answer to his question, a solution to the problem of how to get the lifeship turned toward 20B-40. But he was not destined to be left to puzzle over it in peace. As he sat on his cot with Esteven’s recorder, talking the last day’s entry into it, there was an explosion of noise from between the screens enclosing the middle section of the ship. Shouts, screams, and the sounds of bodies bumping about.

He shoved the recorder into a pocket and went through the gap in the adjoining screen almost as swiftly as he had gone through it when Di had screamed, at the time of the death of the Engineer. In the middle section, Groce had Esteven pinned up against one wall of the lifeship hull and was doing his best to pound the other arbite into unconsciousness. Groce was obviously a good ten years or more older than Esteven. Also he was the smaller, lighter man and very obviously he had no knowledge of how to fight beyond a general idea that he should ball his fists and keep swinging them at another person. But his sheer fury was outweighing these small drawbacks. Esteven, caught between two cots and with his back to the metal wall, could not get away from the furious computecom, and it was plain enough that unless he was rescued, Groce was going to succeed eventually in doing him considerable damage.

Giles hurdled a pair of intervening cots and grabbed Groce by the back of the collar and the slack in his coveralls at his waist.

“Stop that!” he snapped, pulling the computecom back out of arm’s reach of Esteven, who sagged against the wall. “Calm down, Groce... . No, no, don’t try hitting me now. Sit down and be quiet. You, too, Esteven. Sit down on that other cot over there, and tell me what’s going on here.”

“He—he—” Esteven was almost sobbing. The unnatural flushed look Giles had noticed once before was back on his cheek, and the finger he pointed at Groce trembled. “He’s got everything to keep him occupied. He’s got a compute. And he’s got a book, too. All I wanted was a few pages out of the book so that I could write down some music I’ve been composing—”

“All!” shouted Groce. The older man’s voice scaled upward in outrage. “Just a few pages—that’s all? A whole handful of pages tom out of my ancestor’s book on prepositional calculus! I’ve been working the statements in it, to pass the time. But it’s my book—and it’s priceless! It’s over two hundred and twenty-five years old. Do you thing I’m going to rip sheets out of a precious family antique like that, just so he can scribble some homemade music notes on it? What’s he doing composing music, anyway? Nobody writes any real music nowadays except with a compute-tank—”

“Groce!” said Giles. Groce went silent.

“He thinks—” began Esteven.

“You, too,” said Giles. “Be quiet. Now, Groce, let’s see this book.”

Glaring at Esteven, Groce reached into a pocket of his coveralls and brought out a brown-covered volume almost small enough to be hidden in the closed hand. But when Giles took it and opened it, he saw that the little pages did, indeed, have a good deal of white space on them, between and around the blocks of printing diagrams.

“It’s a math book all right,” he said. “Prepositional calculus, you said, Groce?”

“That’s right, Honor, sir,” said Groce, somewhat less truculently. “My grandfather bought it, back before the Green Revolution. It’s an heirloom—from the days when computes took up whole floors in buildings.”

“A book two hundred and twenty-five years old?” Giles nodded. “I don’t blame you for not wanting it damaged, Groce.” He frowned suddenly and took a corner of one page between his middle finger and thumb, rubbing it.

“It’s in remarkably good shape for a book that old,” he said. “How—”

“It’s been plastic-injected. All the original materials have been replaced with single-molecule stuff,” said Groce, proudly. “My father had it done. Cost him the equivalent of a full month’s pay, but it hasn’t shown a touch of wear since then, in fifty-four years.”

“Plastic?”

The word came from Esteven, in an odd voice. He was staring at the book in Giles’ hand.

“That’s right, Esteven,” Giles said. “That’s what Groce just told us. What about it?”

“Why ... nothing,” said Esteven, still staring at the book. “I mean ... I suppose if it’s plastic my stylo wouldn’t work on it. I wouldn’t be able to use the pages to write on, anyway....”

“Damned shame you didn’t think to ask about that before you tried to steal it from me!” Groce spat at the other arbite.

“I did ask you for it first—”

“And I told you no!” shouted Groce. “Do I have to give reasons for not wanting to tear up an heirloom book?”

“It might have been a little wiser if you had,” Giles said to him, dryly, handing back the book. “Here. Keep it someplace where no one can get at it to tear pages out, from now on.”

He turned back into the front section of the ship and his own cot. Behind him the recorder started up, and the familiar three chords of Bosser, backing up the suggestive lyrics of the throaty Singh, followed him.

He sat down on his cot and discovered that Mara had followed him. She was standing over him.

“Yes?” he said, looking up at her.

“Could I show you something?” she asked. Her face was serious, almost grim.

“What is it?” he asked.

“If you’ll come with me—”

A sudden new explosion of voices broke out in the middle section. The Bosser-Singh combination abruptly gave way to a solo instrument sounding a high-pitched bit of wailing melody. Giles shot up from his couch and strode into the middle section, to find Groce trying to tear the recorder out of Esteven’s grasp.

“—and kill that kind of thing!” Groce was shouting. “Give us the Bosser and Singh back. That was good!”

“In a minute ... just a minute,” said Esteven, pleadingly. “Just listen a second to this spinny—”

“What d’you mean, spinny!” snarled Groce. “It’s a lousy kilin, and I hate kilin music!”

“Sir?” Esteven appealed to Giles. “You know music, Honor, sir. You’ve probably had education in it You can tell the difference, can’t you?” Esteven’s trembling fingers were snapping time to the music.

“That’s right it’s a spinny,” Giles said. “But I’m afraid music’s not one of my larger interests, Esteven. The Bosser and Singh suits me as well as anything.”

He started to move on, but Esteven held up a hand, asking him to wait a moment Moved by an obscure sense of pity for the man, Giles did.

“I was right though, sir,” said Esteven. “You do know. You do understand. Would you be surprised if I told you the name of the soloist on that spinny? That’s me. It’s my job arranging and setting up pieces like that I know I can just program an instrumental part and have it come out perfect from the synthesizer. But there’s so few like me nowdays who really know and love their instruments—I always feel you put more into the recording if you have at least a part or two played like that—I mean, if you use a live musician—”

The music stopped suddenly as Groce reached out and stabbed the control button. Bosser and Singh poured forth.

Esteven opened his mouth as if to protest, then closed it silently.

“Groce,” said Giles. Groce looked up at him. “That’s Esteven’s recorder, not yours. Just like your grandfather’s book belongs to you, not him. If you don’t like what’s being played, come and tell me. I don’t want you touching the recorder yourself again.”

“Yes, sir,” muttered Groce, looking down at his cot.

“Give them half an hour or so of what they want,” Giles told Esteven, “then take half an hour to play what you want.”

“Yes, Honor, sir,” said Esteven. The look of gratitude in his eye

s was so overwhelming as to be almost a little sickening. Giles turned to Mara, who was standing just behind him.

“Now,” he said. “What was it?”

“If you’ll come with me,” she said.

She stepped past him and led the way into the rear section, which was empty at the moment. There, she turned to the nearer wall of the hull and the vine on it. She searched among the leaves for a moment, then lifted a stem of them out of the way with her left hand and pointed with her right forefinger.

“Look at this fruit,” she said to Giles, in a low voice.

He stepped close to the vine and brought his gaze down to the fruit she indicated. At first he saw nothing about it that was different from the appearance of the other fruits he had been accustomed to seeing and eating. Then, shading his eyes against the dazzle of the eternal bright lights overhead, he began to make out faint shadows on the ib fruit’s surface. He stepped closer and saw that the shadows were spots of darkness, seemingly just beneath the skin of the fruit.

“I’ve seen one or two fruit before like this,” Mara was saying quietly in his ear. “But none of them had the number of brown spots this one has. When I ran across it, I did some more looking around the vine and found a couple of dozen of the fruit that have at least two or three brown spots like this.”

“Could you show me some of the others?” he asked.

She nodded and led him down along the. vine. With a little searching she uncovered three more fruits with a fair number of spots on them, though not as many as the first one she had shown him.

Giles turned back to examining the vine generally. Superficially, it looked very much the same as it always had been, but after a few moments he came across a leaf that was blackened and curled up. He broke it off thoughtfully, and went looking for more of the same.

He collected four such leaves, then went back to detach the first fruit Mara had shown him.

“I’ll take these to the Captain,” he said to her, and looked down at her with approval. “You were wise not to tell any of the others about this before telling me.”

She gave him a faint, thin smile.

“Even an arbite has a touch of common sense, Honor, sir,” she said.

He could not tell if she meant her tone to be mocking, or not.

“I’ll let you know, of course,” he said, “whatever I learn from the Captain. I appreciate your coming and telling me about this. Meanwhile, keep it to yourself until I’ve talked to the Captain.”

“Of course,” she said.

He turned and left her, heading toward the front of the lifeship and holding the leaves and fruit hidden in his hands as he passed through the middle section. His mind was crawling with a vague uneasiness. Naturally, no system as simple as this could be expected to endure indefinitely. While the lifeships were unused aboard the spaceliner, the nutrient tank would have to be added to at intervals to keep the vine alive and operating. No system was perfect. But his researches back on Earth had told him that it should be good, with the lifeship carrying a full load of passengers, for six months at least. And those aboard here now were far from a full load. He stepped around the edge of the screen hiding the Captain.

The alien officer was sitting in her command chair, her eyes closed.

“Rayumung,” said Giles, in Albenareth, “I need to speak with you.”

She did not answer; nor did she open her eyes. He went closer to her, to the very arm of her command chair. Now hidden himself deep behind the screen that protected her, he spoke again, no louder, but almost in the tiny dark orifice of the alien ear.

“Captain! Captain Rayumung?”

She stirred. Her eyes opened, her head turned, and she looked at him.

“Yes?” she said.

“I need your attention to a matter,” Giles said. “It concerns the ib vine.”

“The vine is not to be disturbed. Take only the fruit as directed.”

“Rayumung,” said Giles, “is your memory failing you? You have never given us directions for using the fruit of the ib. I from my own knowledge informed my people.”

“As long as the knowledge has been made available. Act accordingly.” The eyes in the dark and wrinkled face closed again.

“I repeat,” said Giles, more loudly. “I must have your attention. There is an emergency about the vine.”

“Emergency?” The eyes opened.

“Will the Captain examine this fruit?”

Giles held the fruit he carried, the one Mara had first shown him. The three long dark fingers of the alien’s right hand reached out and took it in their tripodal grip. The Captain held the fruit for a moment, gazing at it, then returned it to Giles.

“Do not eat this. Dispose of it.”

“Why? What’s wrong with the fruit?”

“It will make you ill. Perhaps you will die. Do not eat such fruit.”

“I did not need your advice to caution me about that,” said Giles. “I asked you what was wrong with it.”

“It is no longer wholesome.”

“That, too, was obvious.” Giles had made the mistake of losing his temper with the alien Captain before this. He told himself he would not make it again, now. His voice, in the buzzing Albenareth tones, was icy, but as controlled as the Captain’s. “Look at these leaves, then.”

He held out the four curled and darkened leaves to the Captain. She took them, held them as she had held the fruit, and passed them back.

“The leaves,” she said, “are dead.”

“I can see that,” Giles said. “I want to know why. Why are the leaves dead? Why is the fruit not wholesome, suddenly? What has gone wrong with the ib vine?”

“I have no idea.” The Captain’s voice was distant, almost indifferent. “I am a spaceship officer, not a biotechnician. There are those who could tell us what is wrong with the ib, but they are not here.”

“Have you no tests you can make? How about the nutrient solution from the converter? Can’t you test that to see if there’s anything wrong with it?”

“There is no testing apparatus on board this lifeship.”

“Yes,” said Giles, grimly. “In fact, there is very little of anything aboard this lifeship. Like all your ships, Captain Rayumung, it is falling apart from old age and lack of proper maintenance.”

He had hoped to prod the Captain out of her strange condition of lassitude and into anger. But the attempt did not work.

“You do not understand,” said the Captain, in the same distant voice. “The ships are dying. The Albenareth are dying. But we do not die as lesser races do. We do not choose to curl in on ourselves and perish in the soup of an atmosphere, to be broken down chemically into the soil, and less than sod, from which we came. It is our choice to go proudly to meet our deaths, one by one, as the further Portal lets us pass, until the race of Albenareth are known no longer. You are an alien and do not understand. You will never understand. The ib vine on this lifeship, too, is dying—it does not matter why. Since you are dependent on it, you will die also. It is a matter of chemistry and physical law.”

“What about your responsibility to your passengers?”

“I’ve told you,” said the Captain, “my responsibility is to deliver them—whether they are alive or dead at the delivery point does not matter.”

“I do not believe that,” said Giles. “When you took those of us aboard here, together with the rest of the human passengers who boarded your spaceship above Earth, your responsibility was not indifferent to whether they reached their destination alive or dead.”

“That was then,” said the Captain, “before some one or more of your humans destroyed my ship and cost all Albenareth aboard her great loss of honor. If human actions initiate a logic chain of actions that leads to human deaths, I am not responsible.”

“I do not agree with you,” said Giles. “And in any case, as I have told you, I am responsible for the lives of my fellows aboard. You may be able to excuse your actions to yourself, but I warn you, neither I

nor any other humans will excuse them—and your race needs the payments in metal and energy my race gives yours, if you want to keep these ships of yours running for the next few thousand years—or however long it will take you all to die properly.”

“I will not argue with you,” said the Captain. “What eventuates from the arrival of you humans at Belben, dead or alive, must be the concern of others of my race. It is no longer mine.”

“No longer—” Giles broke off, at the stab of a sudden, sharp suspicion. “Rayumung, is it that you, yourself, don’t expect to reach Belben alive?”

“That is correct. I will not.”‘

Giles stared down at the long, narrow, dark figure in the command chair.

“Why?” he snapped.

The Captain looked away from him, transferring her gaze to the nearer of the two screens on the control console before her—a screen showing the endless darkness of space sprinkled with star’ lights out ahead of the lifeship.

“The ib vine does not have the nutrients I now require,” she said. “Alone, it would nourish me as long as necessary for survival. But I am no longer alone. I carry new life within me—a new life, as yet free of any taint of dishonor, to keep alive the search for whoever destroyed my ship. A new life, if necessary, to found a family line which will never cease from searching until the truth is known. It is a ship’s life, bred of the Engineer and myself, but carrying the honor line of all my officers and crew who were with me while my ship lived. I will die, but my ship’s child will take what it needs from my body and live to land at Belben, to become a ship’s officer and erase the shame of what has happened.”

She fell silent. For a long moment, Giles himself had no words. All at once it leaped into context in his mind—the elastic ties around the limbs of the spacesuit of the Engineer, that could do next to nothing to protect that alien’s life in case of leaks, but which could protect the vital generative area of his central body against the dangers of decompression. That—and what it was that Di had seen, there in the alien blood-marked back of the ship when she had wandered in on the Captain and the dying Engineer.

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

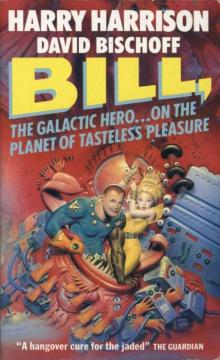

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures