- Home

- Harry Harrison

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Page 9

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Read online

Page 9

"It isn't fair," Dirk said. "Genghis Khan doesn't even belong in this period. How did the Huns get here?"

"That," Splock said, "is less important than what we are going to do about them."

"Any ideas?" Dirk asked.

"Just a moment," Splock said. "I'm thinking. Or rather, thought being lightning-fast, I'm reviewing the thoughts I had when the problem just came up."

"And?" Dirk prompted.

"I have an idea," Splock said. "It's a remote chance, but perhaps we can bring it off. Hold them for as long as you can, Captain. Bill, come with me."

"And what about me?" Illyria-cum-Chinger cried out shrilly as they almost walked on her. "You should show a little consideration!"

"Of course, sure, we didn't forget you," Bill said, realizing they had forgotten her. "Stick with the captain. Keep an eye on him. Be right back. I hope." He looked at Splock suspiciously. "Where are we going?"

"We are going to save the Earth as we know it." Splock took Bill's hand and, with his free hand, made an adjustment to the miniature control panel on his belt. There was a sound of thunder and multiple flashes of lightning. Bill didn't even have time for a good gasp. Suddenly he felt space and time dissolve around him. An icy wind blew around his chops, and he felt himself lifted and carried away by a gigantic wind which was none other than the Wind of Time itself.

After a period of whirling sounds and flashing lights and uncanny smells, Bill found himself standing on a barren plain, or perhaps it was a desert. Bill wasn't too sure. It was colored brown and seemed to be composed mainly of gravel, with some larger rocks for comic relief. Here and there were a few bedraggled thorn bushes, barely subsisting in this dry, sere place. Splock was standing beside him, consulting a small map which he had taken out of the pouch at his waist.

"This ought to be the place," Splock said, frowning, his ears twitching, "Unless this is an out-of-date map. Temporal currents change without notice, so you can't always be sure —"

There was a loud bellowing noise behind them. Bill jumped straight up in the air and whirled, reaching for the weapons he didn't have strapped to his waist.

Splock turned more slowly, as was suitable for someone of his intellect.

"It's just the camel men," Splock said.

"Oh," Bill said. "The camel men. Of course. You didn't mention them before now."

"I didn't think it necessary," Splock said. "I thought you could figure out that much for yourself."

Bill didn't bother to reply that he had had no clues. Splock was one of these very intelligent people who always have an answer for everything and whose explanations make you feel more stupid than you actually are. Or so you hope.

The two camel men, mounted on their high dromedaries, had been waiting patiently. Now one of them addressed Splock in a strange language which Bill's translator, after a moment of fumbling, managed to translate into English.

"Greetings, Effendi."

"Greetings," Splock said. "Please be so good as to take us to your leader."

The camel drivers chattered among themselves in a language, or more likely, a dialect, which Bill's computer didn't have in its repertoire. Whatever it was, Splock seemed to know it, and he broke in with a few well-chosen words which left the camel men laughing in an embarrassed and somewhat respectful fashion.

"What did you say to them?" Bill asked.

"Just a pleasantry," Splock said. "It loses a lot in the translation."

"Tell me anyway," Bill said.

"I told them, may your camel tracks never cross the dismal swamp that leads to the stygian darkness."

"And they laughed?"

"Of course. I used a variant for swamp which can also be construed as meaning 'May your tailbone never suffer the multiple indignities of being kicked around the oasis by the Sultan's bodyguards.' A neat bit of linguistic legerdemain if I may say so myself."

The camel drivers had finished jabbering excitedly between themselves. Now the elder of the two, with the short black beard and the bulging dark eyes, said, "Mount up behind us. We will take you to The Boss."

They got up behind the camel drivers and set forth. At first Bill thought they were going toward the distant mountains. But soon he could make out a square shape far ahead, and battlements, and towers. It was a city they were going to, and a big one.

"What is that place?" Bill asked.

"That ahead of us is Carthage," Splock said. "You've heard of Carthage, haven't you?"

"Where Hannibal came from?"

"You got it in one," Splock said.

"Why are we going there?"

"Because," Splock explained with great patience, "I'm going to make Hannibal an offer he can't refuse. At least I hope he can't."

"Elephants," Hannibal said. "They were my undoing. Did you ever try to refuel a squadron of elephants in the Alps in January?"

"Sounds difficult," Bill said. He was interested to note that Hannibal spoke Punic with a slight southern accent, really a South Balliol Lisp. It threw a new light on this famous man, though Bill wasn't sure what it meant. Neither did his translator, which had pointed out this totally boring fact.

"I had it all there," Hannibal said. "Rome was so cwose to being mine, I could taste it. Tasted wather armpitty and garlicky too. Victory within my grasp! And then that damned Fabius Cunctator with his delaying tactics put paid to my dweam. I could handle him now, beweive me, but at the time delay was a new military tactic. Pwevious to that, it had just been ignorant armies clashing by night and that sort of booshaw. Well, no sense cwying over spilt kvass. Now, what do you strange looking barbarians want? Speak quickly or I'll have you gutted."

"We are here to give you another opportunity," Splock said, talking very fast.

Hannibal was a tall, well-built man. He wore a polished cuirass and a gleaming brass and bronze helmet. They were in Hannibal's audience room at the time. It was not really a major audience room. Hannibal had suffered defeat, and therefore he wasn't allowed to use the main audience room. This was a small audience room put aside for the use of unsuccessful generals. On a sideboard there were sweetmeats, doves' tongues in aspic, french fried mice, that sort of thing, and flasks of tarry wine. Bill had already wandered over to the sideboard, since Splock seemed to have this part of the talk well in hand. There were little pots resting in wire cradles over heating elements which burned olive oil. Bill sampled one of the pots. It tasted like curried goat droppings. He spat it out; it probably was.

"Mind if I try one of these?" he asked Hannibal, pointing to the wine pots.

"Go wight ahead," Hannibal said. "The one in the big jug on the end is wather nice. No tar like the others."

Bill sampled it, tasted, liked what he tasted, glugged another swig.

"Zoinks! What is that stuff?" he asked.

"Palm whiskey," Hannibal said. "Made only in the Highlands of Carthaginia. By an awfully secret pwocess called distilazione."

"Terrific," Bill said, swilling more.

Hannibal returned to his conversation with Splock. This was carried out in low voices, and Bill wasn't much interested anyhow. The palm whiskey had entirely claimed his attention and was quickly destroying his cerebral cortex. He nibbled at some of the repulsive food, which was beginning to taste good, which was a bad sign, then swigged down more of the palm whiskey. Life was not looking too bad at the moment. Bleary, but not bad. Things looked even better when, in response to an unseen signal, or perhaps because it was the regular time for their appearance, a troupe of dancing girls came through the archway, accompanied by three musicians with complicated-looking instruments made of gourds and catgut.

"Hey now!" Bill said. "This is more like it!"

The dancing girls looked toward Hannibal, but he was deep in conversation with Splock and waved them away. They turned to Bill, formed a line in front of him, and started to dance. They were the best kind of dancing girls, tall, wide of hip and generous of breast, with legs that never stopped. Bill's type entirely. They danced for him with many

a flirtatious gesture, like removing their veils one by one while doing a grind and a bump; the musicians grinned and pounded and strummed on their strange instruments; tumescence surged and Bill asked the cute dancer on the end nearest him what she was doing after the show, but she didn't seem to understand Punic.

The dance went on for quite a while, more boring now since they put the veils back on after noticing the effect on Bill. Long enough for Bill to get pleasantly smashed on the palm whiskey, and to burn his mouth on the little green chillies he hadn't noticed he was eating. He was about to ask the musicians if they knew a couple of old songs Bill had learned when he was a kid, but before he got the chance Hannibal and Splock seemed to come to some sort of an agreement. They shook hands and got up and strolled over to Bill. Hannibal made a gesture and the musicians and dancers packed up and left quickly.

"So, it's all settled," Splock said. "Hannibal himself is going to come to our aid. He'll bring five of his crack elephant squadrons. I've assured him we'll handle all the details of servicing his elephants."

"Thash great," Bill said, with some difficulty. He felt like his tongue was wearing a spacesuit. "Didn't seem too difficult, either, neither, wazzah."

"No, I was sure that Hannibal would want a return engagement against the Romans. There was just one trifling condition that I had to agree to."

"What was that?" Bill asked.

Splock hesitated. "I'm afraid you might not like this. But you are so smashed I doubt if you will notice. And you did say you'd do whatever you could to help."

"Whassaht?"

"The Carthaginians have a most interesting custom. Their aid to allies is conditional on a hero from the ranks of said ally agreeing to meet the Carthaginian champion."

"And whossaht?" Bill mouthed dimly, barely aware of the import of Splock's words.

"The word he used was quite unfamiliar to me," Splock said. "I couldn't tell you whom they meant. Or what."

"You mean not man...maybe a...thing?" Bill blinked rapidly as some dim bit of meaning trickled down through alcohol-laden synapses.

Splock nodded. "This is the sort of problem you encounter when you go to the ancient world. Never mind, a trained trooper like you ought to make short work of it, whatever it is."

"What happens if I lose?" Bill asked, sobering rather quickly.

"Not to worry. Hannibal has agreed to help even if you are killed."

"Oh, yeah, wonderful." Sobriety struck like poisoned lightning at this threat to mortality. "Splock, you pointed-eared son of a bitch — what have you gotten me into? I don't even have any of my weapons with me."

"Improvisation," Splock said, "is the first quality of a well-trained soldier. And you can lay off all the ear-insults."

"Come," said Hannibal, interrupting their friendly chat, "we can hold the contest immediately."

Bill reached for the palm whiskey, then decided against it. In fact, uncharacteristically, he was cold sober and regretting it.

Now to tell of the dueling ground of the Carthaginians.

It was inside that portion of the city known as the Sacred Enclosure — a squat black building within which was an enormous amphitheater, its roof open to the blinding African sun. As at a bullfight, there were sunny seats and shady, and these were sold for different prices. Box holders had clay shards with curious figures inscribed on them. Season passholders had to have a man along to carry the massive clay tablet on which was inscribed the dates of the performances and the patron's seat number. When not used for contests, the Black Theater, as the locals called it, staged ballets, music festivals, defloration ceremonies and other priestly fund raisers for the local gods.

The arena was circular, and there were steep tiers of seats up the sides. Already the stands were half full, and more people were streaming in through the entry slits in the basalt walls. Sand had been strewn on the arena floor. It was a bright yellow, in contrast to the black walls of the building, and the gaily colored pennants that flew from four tall masts. Peddlers in long gray smocks trudged up and down the steep steps selling fermented mares' milk, which tasted about as loathsome as it sounds, squirrel sausages and other local specialities. A group of acrobats was already on the arena floor, and a comic actor in satyr mask and three-foot phallus was really warming up the crowd.

In caverns below the arena, Bill was having an argument with Splock.

"I'm not going out there," Bill said, "without a weapon." Bill had refused to put on a special gladiator's costume. Nor had he accepted any of the edged weapons which were laid out before him on a table.

"These look perfectly suitable," Splock said, splanging the edge of one of the swords with his fingernail. "I fail to understand your difficulty."

"I don't know anything about swords, that's my difficulty." Bill said. "I want a gun."

"But these people do not have guns," Splock said.

"I know. That's why I want one."

"That would be hardly sporting," Splock pointed out.

"Sport!" Bill shrieked. "Those mothers want to kill me! Whose side are you on, anyhow?"

"I serve the truth, unemotionally and coolly," Splock said. "And anyhow, I don't have a gun."

"You've got something, though, haven't you?"

"Not really. Only this laser pen. But that's hardly suitable —"

"Gimme!" Bill said, and grabbed it. "What's its range?"

"About ten feet. Three meters, to be exact. At that range it can burn a hole through two-inch steel plating. But Bill, I have to tell you —"

Just then Hannibal and two guards came into the room. "Well?" Hannibal asked. "Is the man from the future ready?"

"Ready," Bill said, putting the pen into the pocket under his pouch and zipping it.

"But you have no sword or lance!"

"You're right. Just pass one of those daggers over. A small one, that's it."

"Guards, escort him to the arena!"

Bill, flanked by guards with lances, marched out into the sunlight. When the crowd caught a look at him, shambling along and blinking in the sunlight, cleaning his nails with the tiny dagger the odds on Bill fell from ten to one to a hundred to one.

"You better take some of that," Bill called out to Splock.

"Bill!" Splock shouted. "There's something I must tell you! That laser pen —"

"I'm not going to give it back," Bill told him.

"But it's discharged, Bill! It hasn't any current left! Bill, not only is it out of energy, it also leaks. I was going to get it fixed at the next Boffritz we passed."

"You can't do this to me!" Bill screamed.

But now he was alone in the middle of the arena. The crowd had fallen silent. Not a sound could be heard except for a faint rustling noise under his tunic.

Bill opened a button. A Chinger stuck out its tiny green head.

"Still with you, Bill," the lizard said.

"Who am I talking to?"

"The computer, of course."

"You'll zap whatever comes up, won't you, computer?"

"Alas, Bill, I am not capable of taking any action in my present form. But I will observe everything and report your struggles to your next of kin."

Just then an iron gate in the arena wall opened. While Bill watched, slack-jawed, something came shambling out.

It was a strange-looking beast indeed. At first Bill mistook it for a lion, because the first thing he looked at was its head. The head was definitely leonine, with a full tawny mane, big almond-shaped yellow eyes, and the sleepily ferocious look that lions have, at least in Carthage. But then he noticed that its body was as thick around as a barrel, and tapered down to a thin scaled tail. So he thought it was a snake with a lion's head. But then he noticed the sharp little hooves, just like the hooves on the goats back home.

"Well, bless my electronic soul," the computer said in a squeaky lizard voice since, of course, it was utilizing the Chinger's body as a source of communication. "I do believe we are looking at a chimera! In my studies of the history of the human

race — and a rather sordid history it is — I have come across references to the creature. Always regarded as mythological. It was long believed that these creatures were mere figments of the ancient imagination. Now we see that they existed literally. And, if I'm not mistaken, the creature is breathing fire, just like Pliny said it would."

"Do something!" Bill cried.

"But how can I?" the computer said. "I am a mere disembodied intelligence in this world."

"Then get out of that Chinger and let Illyria back in!"

"What would a Tsurisian farmgirl know about chimeras?" the computer asked.

"Never mind! Just do it!"

The computer must have done it, because a moment later Bill could hear Illyria's voice, unmistakable even when projected through the larynx and soft palate and unusual dentition of a Chinger.

"Bill! I'm here!"

This talk took place fairly rapidly, although several of the points had to be repeated since the crowd noises made it difficult to hear finer shades of discourse. The chimera was not motionless during this colloquy. First the dreaded beast pawed the ground, scraping aside the sand and scoring the basalt floor of the arena with grooves three inches long with a single strike of its adamantine hooves. Then, noticing Bill, it snorted a double snort of flames, bright red ones with an unhealthy-looking green tinge at their base. Then, fixing its gaze upon Bill, it began to walk, then run, then canter, and at last gallop, toward the intrepid trooper with what appeared to be a four-armed lizard on his shoulder.

"Illyria! Do something!"

"What can I do?" the unhappy girl moaned. "I'm only a tiny green Chinger! Albeit a heavy one from a 10G planet —"

"Shut up!" Bill hinted in a shout of quiet desperation. "Don't you have the power to take over the minds of other creatures? Isn't that a Tsurisian speciality?"

"But of course! What a clever idea! You mean you want me to take over the chimera!"

"And fast," Bill said, running away full tilt now, the chimera breathing flames behind him and gaining rapidly.

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

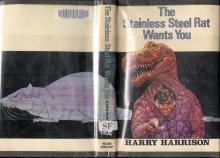

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

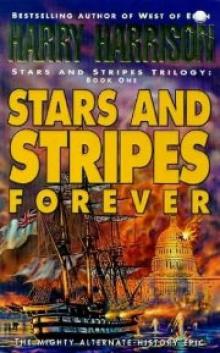

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

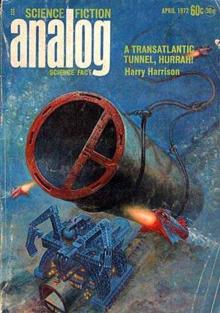

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

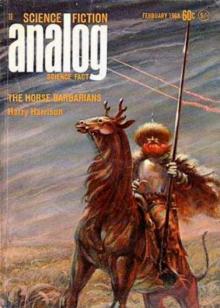

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

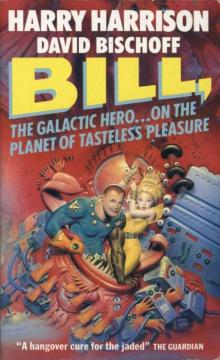

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures