- Home

- Harry Harrison

Make Room! Make Room! Page 8

Make Room! Make Room! Read online

Page 8

“Did you mean that—what you said about Mike?” Shirl asked, after the door had closed. In a plain white dress and with her hair pulled back she looked very young, even innocent, despite the label Mary Haggerty had given to her. The innocence seemed more realistic than the charges.

“How long did you know O’Brien?” Andy asked, fending the question off for a moment.

“Just about a year, but he never talked about his business. I never asked, I always thought it had something to do with politics, he always had judges and politicians visiting him.”

Andy took out his notebook. “I’d like the names of any regular visitors, people he saw in the last week.”

“Now you are asking the questions—and you haven’t answered mine.” Shirl smiled when she said it, but he knew she was serious. She sat down on a straight-backed chair, her hands folded in her lap like a schoolgirl.

“I can’t answer that in too much detail,” he said. “I don’t know that much about Big Mike. About all I can tell you for certain is that he was some sort of a contact man between the syndicate and the politicians. Executive level I guess you would call it. And it has been thirty years at least since the last time he was in court or behind bars.”

“Do you mean—he was in jail?”

“Yes, I checked on it, he’s got a criminal record and a couple of convictions. But nothing recently, it’s the punks who get caught and sent up. Once you operate in Mike’s circle the police don’t touch you. In fact they help you—like this investigation.”

“I don’t understand….”

“Look. There are five, maybe ten killings in New York every day, a couple of hundred felonious assaults, twenty, thirty cases of rape, at least fifteen hundred burglaries. The police are understaffed and overworked. We don’t have time to follow up any case that isn’t open and shut. If someone gets murdered and there are witnesses, okay, we go out and pick the killer up and the case is closed. But in a case like this, frankly, Miss Greene, we usually don’t even try. Unless we get a make on the fingerprints and have a record on the killer. But the chances are that we don’t. This city has a million punks who are on the Welfare and wish they had a square meal or a TV or a drink. So they try their hand at burglary to see what they can pick up. We catch a few and send them upstate on work gangs, breaking up the big parkways with pickaxes to reclaim the farmland. But most of them get away. Once in a while there is an accident, maybe someone comes in while they are pulling a job, surprises them while they are cleaning out the place. If the burglar is armed there may be a killing. Completely by accident, you understand, and the chances are ninety-nine out of a hundred that something like this happened to Mike O’Brien. I took the evidence, reported the case—and it should have died there. It would have if it had been anyone else. But as I said, Big Mike had plenty of political contacts and one of them put on some pressure to make a more complete investigation, and that is why I am here Now—I’ve told you more than I should, and you’ll do me a big favor if you forget all about it.”

“No, I won’t tell anyone. What happens next?”

“I ask you a few more questions, leave here, write up a report—and that will be the end of it. Lots of other work is piling up behind me and the department has already put more time into the investigation than it can afford.”

She was shocked. “Aren’t you going to catch the man who did it?”

“If the fingerprints are on file, we might. If not—we haven’t got a chance. We won’t even try. Aside from the reason that we have no time, we feel that whoever did Mike in performed a social service.”

“That’s terrible!”

“Is it? Perhaps.” He opened his notepad and was very official again. He had finished with the questions by the time Kulozik came back with latent prints from the cellar window and they left the building together. After the cool apartment the air in the street hit like the blast from an open furnace door.

7

It was after midnight, a moonless night, but the sky outside the wide window could not equal the rich darkness of the polished mahogany of the long refectory table. The table was centuries old, from a monastery long since destroyed, and very valuable, as were all the furnishings in the room: the sideboard, the paintings, and the cut-crystal chandelier that hung in the center of the room. The six men grouped around the end of the table were not valuable at all, except in a financial sense, although in that way they were indeed very well off. Two of them were smoking cigars, and the cheapest cigar you could buy cost at least ten D’s.

“Not every word of the report if you please, Judge,” the man at the head of the table said. “Our time is limited and just the results will be all we need.” If anyone there knew his real name they were careful not to mention it. He was now called Mr. Briggs and he was the man in charge.

“Surely, Mr. Briggs, that will be easy enough,” Judge Santini said, and coughed nervously behind his hand. He never liked these sessions at the Empire State Building. As a judge he shouldn’t be seen here too often with these people. Besides, it was a long climb and he had to think about his ticker. Particularly in this kind of weather. He took a sip of water from the glass in front of him and moved his glasses forward on his nose so that he could read better.

“Here is what it boils down to. Big Mike was killed instantly by a blow on the side of the head, done with a sharpened tire iron that was also used to break into the apartment. Marks made on a jimmied-open basement window match the ones on the door and they both fit the jimmy, so it looks as though whoever did it got in that way. There were clear fingerprints on the iron and on the basement window, the same prints. So far the prints appear to be of a person unknown, they do not match any of the fingerprints on file in the Bureau of Criminal Identification, nor are they the prints of O’Brien’s bodyguard or girl friend, the ones who found the body.”

“Who do the fuzz think done it?” one of the listeners asked from around his cigar.

“The official view is—ah, death my misadventure you might say. They think that someone was burgling the apartment and Mike walked in and surprised him, and Mike was killed in the struggle.”

Two men started to ask questions but shut up instantly when Mr. Briggs began to speak. He had the gloomy, serious eyes of a hound dog, with the matching sagging lower lids and loose dewlaps on his cheeks. The pendant jowls waggled when he talked.

“What was stolen from the apartment?”

Santini shrugged. “Nothing, from what they can tell. The girl claims that nothing is missing and she ought to know. The room was taken apart, but apparently the burglar was jumped before he finished the job and then he ran in a panic. It could happen.”

Mr. Briggs pondered this, but he had no more questions. Some of the others did and Santini told them what was known. Mr. Briggs considered for a while then silenced them with a raised finger.

“It appears that the killing was accidental, in which case it is of no importance to us. We will need someone to take over Mike’s work—what is it. Judge?” he asked, frowning at the interruption.

Santini was sweating. He wanted the matter settled so he could go home, it was after I A.M. and he was tired. He wasn’t used to being up this late any more. But there was a fact that he had to mention, it might be important and if it was noticed later and it came out that he had known about it and said nothing … it would be best to get it over with.

“There is one thing more I ought to tell you. Perhaps it means something, perhaps not, but I feel we should have all the information in front of us before we—”

“Get on with it, Judge,” Mr. Briggs said coldly.

“Yes, of course. It’s a mark that was on the window. You must understand that all the basement windows are coated with dust on the inside and that none of the others were touched. But on the window that was jimmied open, through which we can presume the killer entered the building, there was a design traced in the dust. A heart.”

“Now what the hell is that supposed to mean?” on

e of the listeners growled.

“Nothing to you, Schlacter, since you are an American of German extraction. Now I am not guaranteeing that it means anything, it may just be a coincidence, meaningless, it could be anything. But just for the record, just to get it down, the Italian word for heart is cuore.”

The atmosphere in the room changed instantly, electrified. Some of the men sat up and there was a rustle of shifting bodies. Mr. Briggs did not move, though his eyes narrowed. “Cuore,” he said slowly. “I don’t think he has enough guts to try and move into the city.”

“He’s got his hands full in Newark. He got burned once coming here, he’s not going to try it again.”

“Maybe. But he’s half out of his head I hear. On the LSD. He could do anything….”

Mr. Briggs coughed and they were all quiet on the instant. “We are going to have to look into this,” he said. “Whether Cuore is trying to move into our area or whether someone is trying to stir up trouble and blaming it on him; either way we want to find out. Judge, see to it that the police continue the investigation.”

Santini smiled but his fingers were knotted tightly together under the table. “I’m not saying no, mind you, not saying it can’t be done, just that it would be very difficult. The police are very shorthanded, they don’t have the personnel for a full-scale investigation. If I try to pressure them they’ll want to know why. I’ll have to have some good answers. I can have some people work on this, make some calls, but I don’t think we can get enough pressure to swing it.”

“ You can’t get enough pressure, Judge,” Mr. Briggs said in his quietest voice. Santini’s hands were tembling now. “But I never ask a man to do the impossible. I’ll take care of this myself. There are one or two people I can personally ask to help out. I want to know just what is happening here.”

8

Through the open window rolled the heat and stench, the sound of the city, a multivoiced roar that rose and fell with the hammered persistence of waves breaking on a beach; an endless thunder. In sudden punctuation against this background of noise there came the sound of broken glass and a jangled metallic crash; voices rose in shouts and there was a long scream at the same instant.

“What? What …?” Solomon Kahn grumbled, stirring on the bed and rubbing his eyes. The bums, they never shut up, never let you grab a little nap. He got up and shuffled to the window, but could see nothing. They were still shouting—what could have made the noise? Another fire escape falling off? That happened often enough, they even showed it on TV if there was a gruesome picture to go with it. No, probably not, just kids breaking windows again or something. The sun was down behind the buildings but the air was still hot and foul.

“Some lousy weather,” he muttered as he went to the sink. Even the boards in the floor were hot on the soles of his bare feet. He sponged off some of the sweat with a little water, then turned the TV on to the Music-Time station. A jazz beat filled the room and the screen said 18:47, with 6:47 P.M. underneath in smaller numerals for all the yuks who had dragged through life without managing to learn the twenty-four-hour clock. Almost seven, and Andy was on day duty today, which meant he should have been through by six, though they never left on time. Anyway, it was time to get the chow going.

“For this the Army gave me a fine fifteen-grand education as an aviation mechanic,” he said, patting the stove. “Finest investment they ever made.” The stove had started life as a gas burner, which he had adapted for tank gas when they had closed off the gas mains, then had installed an electric heating element when the supplies of tank gas had run out. By the time the electric supplies became too erratic—and expensive—to cook with, he had installed a pressure tank with a variable jet that would burn any inflammable liquid. It had worked satisfactorily for a number of years, consuming kerosene, methanol, acetone and a number of other fuels, balking only slightly at aviation gas while sending out a yard-long streamer of flame that had scorched the wall just before he could adjust it. His final adaptation had been the simplest—and most depressing. He had cut a hole in the back of the oven and run a chimney outdoors through another hole hammered through the brick wall. When a solid-fuel fire was built on the rack inside the oven, an opening in the insulation above it let the heat through the front ring.

“Even the ashes stink like fish,” he complained as he shoveled out the thin layer of powdery ash from the previous day. These he threw out the window in an expanding gray cloud and was gratified when he heard a cry of complaint from the window on the floor below. “Don’t you like that?” he shouted back. “So tell your lousy kids not to play the TV at full blast all night and maybe I’ll stop dumping the ashes.”

This exchange cheered him, and he hummed along with The Nutcracker Suite which had replaced the nameless jazz composition—until a burst of static suddenly interrupted the music, drowning it out. He mumbled curses under his breath as he ran over and hammered on the side of the TV set with his fist. This had not the slightest effect. The static continued until he reluctantly turned the TV off. He was still muttering angrily when he bent to fire up the stove.

Sol placed three oily gray bricks of seacoal on the rack and went over to the shelf for his battered Zippo lighter. A good lighter that, bought in the PX when?—must be fifty years ago. Of course most of the parts had been replaced since that time, but they didn’t make lighters like this any more. They didn’t make lighters at all any more. The seacoal spluttered and caught, burning with a small blue flame. It stank—offish—and so did his hands now: he went and rinsed them off. The stuff was supposed to be made of cellulose waste from the fermentation vats at the alcohol factory, dried and soaked with a low-grade plankton oil to keep it burning. Rumor had it that it was really made of dried and pressed fish guts from the processing plants, and he preferred this to the official version, true or not.

His miniature garden was doing well in the window box. He plucked the last of the sage and spread it out on the table to dry, then lifted the plastic sheeting to see how the onions were doing. They were coming along fine and would be ready for pickling soon. When he went to rinse off his hands in the sink he looked quizzically at his beard in the mirror.

“It needs trimming, Sol,” he told his image. “But the light is almost gone so it can wait until morning. Still, it wouldn’t hurt none to comb it before you dress for dinner.” He ran a comb through his beard a few times, then tossed the comb aside and went to dig a pair of shorts out of the wardrobe. They had started life many years earlier as a pair of Army suntan trousers, and since then had been cut down and patched until they bore little resemblance to the original garment. He was just pulling them on when someone knocked on the door. “Yeah,” he shouted, “who is it?”

“Alcover’s Electronics,” was the muffled answer.

“I thought you died or your place burned down,” Sol said, throwing the door open. “It’s only been two weeks since you said you would do a rush job on this set—which I paid for in advance.”

“That’s the way the electron hops,” the tall repairman said calmly, swinging his valise-sized toolbox onto the table. “You got a gassy tube, some tired components in that old set. So what can I do? They don’t make that tube any more, and if they did I couldn’t buy it, it would be on priority.” His hands were busy while he talked, hauling the TV down to the table and starting to unscrew the back. “So how do I fix the set? I have to go down to the radio breakers on Greenwich Street and spend a couple of hours shopping around. I can’t get the tube, so I get a couple of transistors and breadboard up a circuit that will do the same job. It’s not easy, I tell you.”

“My heart bleeds for you,” Sol said, watching suspiciously as the repairman took the back off the set and extracted a tube.

“Gassy,” the man said, looking sternly at the radio tube before he threw it into his toolbox. From the top tray he took a rectangle of thin plastic on which a number of small parts had been attached, and began to wire it into the TV circuit. “Everything’s make

shift,” he said. “I have to cannibalize old sets to keep older ones working. I even have to melt and draw my own solder. It’s a good thing that there must have been a couple of billion sets in this country, and a lot of the latest ones have solid state circuits.” He turned on the TV and music blared across the room. “That will be four D’s for labor.”

“Crook!” Sol said. “I already gave you thirty-five D’s….”

“That was for the parts, labor is extra. If you want the little luxuries of life you have to be prepared to pay for them.”

“The repairs I need,” Sol said, handing over the money. “The philosophy I do not. You’re a thief.”

“I prefer to think of myself as an electronic grave robber,” the man said, pocketing the bills. “If you want to see the thieves you should see what I pay to the radio breakers.” He shouldered his toolbox and left.

It was almost eight o’clock. Only a few minutes after the repairman had finished his job a key turned in the lock and Andy came in, tired and hot.

“Your chunk is really dragging,” Sol said.

“So would yours if you had a day like mine. Can’t you turn on a light, it’s black as soot in here.” He slumped to the chair by the window and dropped into it.

Sol switched on the small yellow bulb that hung in the middle of the room, then went to the refrigerator. “No Gibsons tonight, I’m rationing the vermouth until I can make some more. I got the coriander and orris root and the rest, but I have to dry some sage first, it’s no good without that.” He took out a frosted pitcher and closed the door. “But I put some water in to cool and cut it with some alky which will numb the tongue so you can’t taste the water, and will also help the nerves.”

“Lead me to it!” Andy sipped the drink and managed to produce a reluctant smile. “Sorry to take it out on you but I had one hell of a day and there’s more to come.” He sniffed the air. “What’s that cooking on the stove?”

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

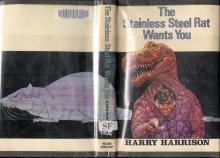

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

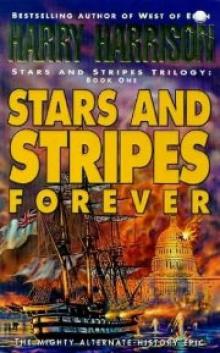

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

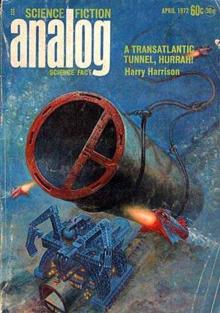

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

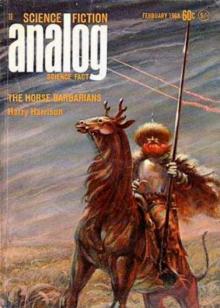

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

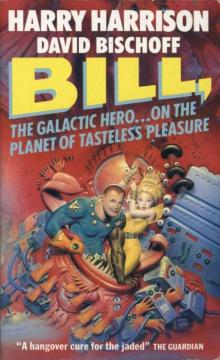

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures