- Home

- Harry Harrison

Winter in Eden e-2 Page 8

Winter in Eden e-2 Read online

Page 8

“I will share it with my friend,” he said.

Kalaleq beamed with happiness as he quickly slashed the liver in half with his flint knife. Kukujuk was a boy who was thinking like a man, knowing it was always right to share, better to give than to take.

Harl took the bloody gobbet, unsure what to do with it. Kukujuk showed him, chewing on his own piece industriously, rubbing his stomach at the same time. Harl hesitated — then watched with amazement as Kalaleq made a little hole in the back of the rabbit’s skull and sucked the brain out After seeing this chewing the raw liver was nothing. It even tasted good.

CHAPTER EIGHT

Armun was not as ready to eat her meat raw as the boy had been. Freshly caught prey was one thing, she had eaten that before, but not the kind of meat Angajorqaq took from a niche in the dirt wall. It was ancient, decayed and stinking. Angajorqaq took little notice of this, as she cut off a piece for herself, then one for Armun. Armun could not refuse — but neither could she put it into her mouth. She held it reluctantly in her fingertips, it was slimy to the touch, and wondered what to do. If she refused to eat it would be an insult to hospitality. She looked desperately for a way out. She put Arnwheet down onto the furs where he chewed happily on the leathery smoked meat, then turned away, raising her hand to her mouth as though eating the piece she had been given. She kept this pretense up as she pushed aside the door hangings and went to the travois. Out of sight now she hid the meat among her skins and found the open bladder of murgu meat. The jellified, almost-raw flesh that the Tanu ate so reluctantly might appeal to the Paramutan.

It did, tremendously. Angajorqaq found the flavor wonderful and called out to Kalaleq to join them, to try this new thing. He ate it with bloodied hands, crying aloud how fine it was between chewing on large mouthfuls. They also gave some to Kukujuk and Harl took a portion as well. While they ate Angajorqaq had heated water over a small fire in a stone bowl, poured it over dried leaves in the leather cups to make an infused tea. Kalaleq sipped his noisily, then ate the leaves from the bowl. Armun tried hers and liked it. This day was ending far better than it had begun. The dugout was warm and free of drafts. She could eat and rest — and not fall asleep, as she had every other night — with the fear of the next day’s walk heavy upon her.

In the morning Kalaleq rooted deep in the back of the hut and dragged rolled bundles out for her inspection. Some were cured skins, black lengths so large she could not imagine the creature they had been taken from. There were also sewn hides filled with thick white fat. Kalaleq scooped out some to taste, offered it to her. The flavor was rich and filling. Arnwheet wanted to try it too. “Eat, eat!” he said and she let him lick her fingers.

Now Kalaleq went through a great amount of play-acting. Rolling and unrolling the hides, pointing to Armun, then pointing back down the trail, holding out his flint knife in one hand, shaking a hide out with the other, then changing hands and calling out, “goodbye”. It was all quite mysterious.

Not to Harl, who seemed to understand these people better than she did.

“I think he wants to know where other Tanu are. He wants to give them some of the fat.”

Armun pointed to herself and the two boys, then back down the trail and said goodbye over and over. When Kalaleq finally understood her meaning he sighed deeply and rerolled the hides, then carried them down to the shore. Kukujuk hurried to help him and Harl joined in as well. After one trip to the water’s edge he ran back to Armun shouting with excitement and pointing.

“See, see that big black rock there! It’s not a rock, not at all. Come see. It’s a boat, that’s what it is.”

Arnwheet stumbled after them, through the dunes and over the dried clumps of grass to the sandy shore. Harl was right, the black lump had the lines of a boat, upside down with its bottom in the air. Kalaleq was going over this carefully, poking it to be sure that there were no openings. It was a strange boat, not hollowed out from a tree like Tanu boats, but made instead from a single large black hide. When Kalaleq was satisfied with his inspection he bent and seized one edge and heaved the boat over. Harl hung from the gunwhale to look inside and Arnwheet shouted until he had been picked up and could see in too.

It was of amazing construction. Thin lengths of wood had been tied together to shape it and give it strength. The hide had been stretched over this to make the outer fabric of the boat. Armun could see now how the hide had been cut to fit the shape of the boat, then sewn back together again. The seams were covered with the same black substance that made the leather cups waterproof. It was a wonder to behold.

Now that Kalaleq had decided to leave, no time was wasted at all. Their belongings were carried down from the dugout, even the hide door cover, and piled on the sand. Everyone joined in, even Arnwheet staggered under the burden of one of the furs. When everything had been tumbled onto the shore, Kalaleq pushed the boat out into the water. It rode there, rocking in the small waves, and Kalaleq climbed inside. There seemed to be a special place for stowing everything that only he knew about, so there was much shouted instruction as the stores were handed to him a piece at a time. When Angajorqaq passed him the supplies from Armun’s travois she knew it was time for a decision to be made — or perhaps it had already been made for her. She looked back at the dunes, with the hills beyond, and knew that only frozen death awaited her there. There was really no choice, none whatsoever. Wherever the Paramutan were bound she must go with them.

Harl clambered in after Kukujuk and Armun handed up Arnwheet who laughed and thought it was great fun. Angajorqaq urged her ahead with soft pats and she climbed into the boat herself. Angajorqaq sat on the sand and unwrapped her leg coverings and threw them into the boat. Like her face and hands, soft brown fur covered her legs as well. Then she hiked up her leather skirts and stepped into the water to push out the boat, shrieking at its icy embrace. Kalaleq had an oar and when the boat was free of the sand Angajorqaq hurled herself headfirst into it, her squeals of laughter muffled by her clothing that had fallen over her face. Armun helped her to pull it free and down over the wet fur of her legs, smiling to herself and amazed at the way the Paramutan laughed so much of the time.

Kalaleq paddled strongly for the rest of the day, right through the discomfort of a rain squall, driving rain with sleet mixed into it, and on into the afternoon. He called out when he was hungry and Angajorqaq fed him deliciously rotten bits of meat, once laughing so hard he almost could not paddle when he bit her finger instead of the meat. Armun huddled under an open hide, holding the boys to her for warmth, and marveled at everything. Only at dusk did Kalaleq paddle back closer to shore, looking for a spot to land for the night. He ran the boat up on a smooth sand beach and they all labored to drag it above the tide line.

For days without number it went on like this. Kalaleq rowed steadily all day, every day, apparently immune to fatigue. Angajorqaq hummed when she baled out the boat with a leather cup, as much at home here as she had been on land. Armun grew sick with the constant motion, lay under the furs and shivered most of the day, holding to Arnwheet who shared her queasiness. After the first few days Harl became used to the movement and joined Kukujuk in the bow where they hung out fishing lines and talked to each other — each in his own language.

The days passed like this and there was no way to keep track of time. The weather worsened as they went north, the waves growing higher so that they bobbed like a bit of driftwood over the mountainous seas. The storms finally died away, but the air remained cold and dry. Armun was lying under the furs, clutching Arnwheet, more than half-asleep when she became aware that Harl was shouting her name.

“We’re coming to something, look ahead. Ice, black things on it, can’t tell what they are.”

The ice was a solid sheet that filled the large bay. There was more ice floating in the sea and they had to thread their way between the floating lumps. To the north even larger icebergs were visible in the hazy distance. Kalaleq was pointing the boat toward dark lumps that littered the icy su

rface ahead. When they came closer it could be seen that they were boats lying bottom up. Only when they had reached the ice sheet did Armun see that most of the boats were many times larger than the one that they were in. It was an incredible sight.

Kukujuk stood on the gunwhale — then jumped up onto the ice when they brushed against it. He used the braided leather line to secure them to one of the broken irregularities of ice — then ran away toward the shore.

Armun had not realized how weak she had become from the voyage. It took Kalaleq and Angajorqaq together to help her up onto the ice. Arnwheet was passed up to her and she sat, shivering and holding him squirming to her, while the unloading started. It had barely begun when Kukujuk came running back with a number of Paramutan hurrying after him. Hunters and women, they marveled at the strangers’ skin and hair, running their hands over Harl’s head until he darted away from them. There were shrieks of laughter at this: then the unloading began in earnest. Soon the bundles were being carried toward the shore and the boat dragged from the sea to join the others on the ice. Armun staggered after them, Arnwheet stumbling in her wake, until one of the hunters seized him and carried him, shouting happily, on his shoulders.

They passed a group that had been erecting a black-skin tent on the ice; they stopped work and gaped at the newcomers. Behind them were other tents, some of them protected against the wind by an outer covering of snow blocks. They were scattered over the ice, as many of them as there were tents in two, maybe three sammads Armun thought, stumbling with fatigue. Smoke rose up from most of them and she knew that there would be fires and warmth. And safety. The wind caught up snow from the drifts and blew it stinging against her face. Winter had already arrived here in the north, snow and ice.

But they passed the security of the tents and walked on toward the shore. Here the snow-covered sea ice was piled high and broken where it reached the land, difficult to climb over. Beyond it the shore was smooth, rising up to a steep hill. Huddled at the base of this hill, half dug into the soil of its slopes, were a few more of the black-skin tents.

Angajorqaq pulled at her hand, hurried her toward one of the black-domed tents. It was sealed shut and Kalaleq was unlacing the entrance. All of the bundles from the boat had been dumped beside it in the snow. Kalaleq pushed his way in and must have lit a fire that was already laid, for smoke quickly burst from the opening at the top. With the feel of solid ground beneath her feet Armun’s sickness from the voyage soon disappeared and she joined the others in dragging in the bundles and furs. It was all right. Everything was going to be all right. She was safe, Arnwheet and Harl were safe. They would all live to see the spring. With this thought she seized up the child, held him tightly to her as she sat down heavily on the heaped furs.

“Build the fire quickly,” Angajorqaq called out. “Hair-of-sunlight is tired, I can tell by looking at her. Hungry and cold. I will get food.”

“We must move this paukarut onto the ice,” Kalaleq said between puffs of breath to encourage the fire. “The bay is frozen, winter is really here.”

“Tomorrow. All will rest first.”

“We will do it tomorrow. The ice is warmer than the land now, the sea water below it will keep the cold away. And I will cut snow to keep out the wind. It will be warm and we will eat and have good fun.”

Thinking of this made him smile with pleasure and anticipation and he reached for Angajorqaq to have some fun now, but she slapped his hand away. “No time,” she said. “Later. Eat first.”

“Yes — eat first! Hunger makes me weak.” He groaned in mock agony, but could not stop himself from smiling at the same time. It was going to be a good winter, a very, very good winter.

CHAPTER NINE

esseka‹asak, elinaabele nefalaktus* tus’ilebtsan tus’toptsan. alaktus’tsan nindedei yilanènè.

When the wave breaks on the shore, small swimming things in it die, are eaten by the birds that fly, they are eaten by animals that run, Yilanè eat them all.

Yilanè apothegm

Lanefenuu had been Eistaa of Ikhalmenets for so many years that only the oldest of her associates could remember the previous eistaa; even fewer of these could recall her name. Lanefenuu was large in spirit as well as body — a head taller than most Yilanè — and as eistaa had wrought great physical changes to the city. The ambesed, where she now sat in the place of honor, had been constructed by her: the old ambesed continued its existence as a field of fruit trees. Here, in a natural bowl on the hillside above the city and the harbor, she had shaped an ambesed for her own pleasure. The morning sun fell full upon her raised seat of inlaid wood to the rear of the bowl, even while the rest was in shadow. Behind her, conforming to the natural curve of the land, were beautifully worked wooden panels, carved and painted so realistically that during the daylight hours there were always fargi pressed close and gazing in gape-jawed admiration. It was a seascape of dark blue waves and pale blue sky, enteesenat leaping high while the dark form of an uruketo stretched from one end to the other, almost life-size. At the top of the high fin a figure had been carved, the replica of the uruketo’s commander, which bore more than a chance resemblance to the Eistaa seated below it. Lanefenuu had commanded an uruketo before rising to the eminence of her present position, still commanded one in spirit. Her arms and the upper portion of her body were painted with patterns of breaking waves. Every morning Elililep, accompanied by another male to carry his brushes and pigments, was brought from the hanalè in a shrouded palanquin to trace the designs. It was obvious to Lanefenuu that males were more sensitive and artistic: it was also good to take a male every morning. Elililep’s brush-carrier was made to satisfy her, for Elililep himself was too valuable to end up on the beaches. It was Lanefenuu’s firm belief — though she never mentioned it to Ukhereb knowing that the scientist would sneer — that this daily sexual satisfaction was the reason for her continued longevity.

This day she was feeling her years. The wintry sunlight did not warm her and only the body heat of the living cloak wrapped around her kept her from sinking into a comatose sleep. And now she had added to all her other worries the burden of despair that the newly arrived commander had placed upon her. Alpèasak the jewel to the west, the hope of her own city, gone. Destroyed by crazed ustuzou — if Erafnais could be believed. Yet she must be believed for this was no second or thirdhand report passed on by yileibe fargi. Erafnais, who commanded an uruketo, the supreme responsibility, had been there, had seen with her own eyes. And the other survivor, Vaintè, she who had grown the city and had witnessed its destruction. She would know more about what had happened than the commander, who had been in her uruketo the entire time. Lanefenuu shifted on her seat and signed for attention. Muruspe, the aide who never left her side, moved quickly forward, ready for instruction.

“Muruspe, I wish to see the newcomer called Vaintè who arrived on the uruketo this day. Bring her to me.”

Muruspe signed instant obedience and hurried to the attendant fargi and repeated Lanefenuu’s message precisely. When she asked them to speak it back to her some of them fumbled, bad memory or weakness in speech, it did not matter. She sent these away, shame-of-failure hurrying them from sight, then made the rest repeat the Eistaa’s command until they all had it right.

Out of the ambesed they went in all directions, hurrying with pride as they bore their Eistaa’s message. Each one they asked spread the word even further through the city until, within a very short length of time, one of Ukhereb’s assistants hurried into her presence signing information-of-great-importance.

“The Eistaa has sent word through the city. The presence of your guest Vaintè is required.”

“I go,” Vaintè said, standing. “Lead me there.”

Ukhereb waved her assistant away. “I will take you Vaintè. It is more appropriate. The Eistaa and I labor together for the cause of Ikhalmenets — and I fear I know what she wishes to discuss with you. My place is there at her side.”

The ambesed was as empty as though it w

ere night, not clouded day. The milling fargi had been driven away and now minor officials and their assistants stood at all the entrances to prevent their return. Facing outward to assure the Eistaa’s privacy. Lanefenuu’s rule was firm, this was her city, and if she preferred the privacy of the entire ambesed rather than that of a small chamber, why then that was what she had. Vaintè admired the erect strength of the tall, stern figure sitting against the painted carvings, felt at once that she was with an equal.

Vaintè’s feelings were in the firmness of her pace as she came forward, not following but walking beside Ukhereb, and Lanefenuu found great interest in this, for none had approached her as an equal since the egg of time.

“You are Vaintè from Alpèasak just arrived. Tell me of your city.”

“It has been destroyed.” Movements of pain and death. “By ustuzou.” Qualifiers that multiplied the earlier statements manifold.

“Tell me everything you know, in greatest detail, starting from the beginning, and leave nothing out for I want to know why and how this came about.”

Vaintè stood legs widespread and straight and was long in the telling. Lanefenuu did not stir or react all of that time, although Ukhereb was moved to pained motions and small cries more than once. If Vaintè was less than frank about some of her relationships with the ustuzou captive, particularly in the matter of the new thing called lies, this was only an error of omission and the story was a long one. She also left out all references to the Daughters of Death as not being relevant, to be discussed at some future time. Now she told simply and straightforwardly how she had built the city, how the ustuzou had killed the males on the birth-beaches, how she had defended the city against the enemy from without and had been forced into peaceful aggression in that defense. If she stressed the creatures’ implacable hatred of Yilanè that was merely a fact. When she reached the end she controlled all of her feelings as she described the final destructions and death, the flight of the few survivors. Then she was finished, but the position of her arms suggested that there was more to be spoken of.

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

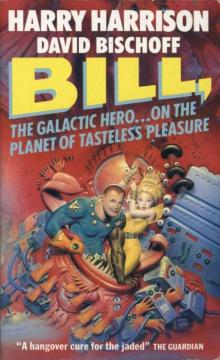

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures