- Home

- Harry Harrison

The Technicolor Time Machine Page 7

The Technicolor Time Machine Read online

Page 7

“Hey…” Barney said, just as the whole thing vanished, leaving nothing but the jeep tracks and the impression of the rows of tires on which the platform rested. He hadn’t intended Tex to go on with the others.

A cloud passed in front of the sun and he shivered. The gulls were settling down at the water’s edge again and the only sound now was the distant rush of the surf as the small waves broke on the beach. Barney glanced at the cigarette pack, the only familiar thing in the alien landscape, and shivered again.

He never looked at his watch, but surely no more than a minute or two passed. Yet in that short time he realized only too well how Charley Chang had felt, stranded on prehistoric Catalina with the eyes and teeth, and he hoped that Jens Lyn wasn’t too unhappy after his two months’ stay. If his conscience had not been eroded away by years in the movie business he might have felt a twang of pity for them. As it was he just felt sorry for himself. The cloud moved away and the sun shone warmly upon him, but he was still cold. For those few minutes he felt alone and lost in a manner he had never experienced before.

The platform appeared and dropped a few inches into the meadow close by.

“About time,” he shouted, the authority coming back with a rush as he stood and squared his shoulders. “Where have you been?”

“In the twentieth century—where else?” the professor said. “You have not forgotten point K already, have you? In order to come forward these few minutes in your subjective time I had to first return the time platform to the time we had left, then return here with the correct physical and temporal displacement. How long did it take—from your point of view?”

“I don’t know, a few minutes I suppose.”

“Very good, I should say, for a round trip of approximately two thousand years. Let us say five minutes, that would give a microscopically small figure for the error of…”

“All right, Prof, work it out on your own time. We want to get the company back in time and to work. Drive that jeep off and you two stay here with it. We’ll start shuttling back the vehicles and I want you to move them as soon as they arrive so we can have room for the next ones. Let’s roll.”

This time Barney returned with the platform and never for an instant did he think about how the two men must feel who had been left behind.

The transfer went easily enough. Once the first few trips had been made the trucks and trailers moved smoothly through the doors of the sound stage and vanished into the past. The only mishap was on the third transfer when a truck overhung the platform, so that when the time trip was made two inches of exhaust pipe and half a license plate clattered to the floor. Barney picked up the piece of pipe and looked at the shining end, flat and smooth, as if it had been polished. Apparently this bit had been outside the time field and had simply stayed behind. It could happen as easily to an arm.

“I want everyone inside the vehicles during the trip, all except the professor. We can’t afford accidents.”

A tractor towing the motorboat trailer and the deepfreeze truck made up the last load, and Barney climbed on after them. He took one last look at the California sunshine, then signaled the professor to take it away. His watch said 11:57, just before noon on Saturday as the twentieth century winked out and the eleventh century appeared, and he took a deep, relieved breath. Now time—in the century they had left—would have a stop. As long as they stayed in this era to film the picture, no matter how long they took, no time would elapse back home. When they returned with the film it would be noon Saturday, almost two full days before the Monday deadline. For the first time the pressure tension drained away. Then he remembered that he had an entire picture to shoot, with all the problems and miseries that would entail, and the pressure dropped heavily back onto his shoulders and the knot of tension returned, full strength.

A roar of sound burst over him as the tractor driver revved up his engine, and the clear air was filled with reeking exhaust. Barney got out of the way as the motorboat trailer was carefully backed off, and he looked across the meadow. The trucks and trailers were scattered about at random, though some of them had been drawn up in a circle like a wagon train getting ready for the Indians. A few figures were visible, but most of the people were still asleep. Barney wished that he were too, but he knew that he wouldn’t sleep even if he tried. So he might as well get some work done.

Tex and Dallas were just settling down in the grass with cushions from the jeep when he came up. “Catch,” he said, flipping a quarter toward Dallas, who grabbed it out of the air. “Toss. I want one of you to go with me to pick up Jens Lyn, the other can catch up on his beauty sleep.”

“Tails you go,” Dallas said, then cursed at George Washington’s portrait. Tex laughed once, then settled himself down.

“You know,” Dallas said, as they drove down to the beach, “I don’t even know where we are.”

“The Orkney Islands,” Barney said, watching the gulls rocketing into the air before them, screaming insults.

“My geography was always weak.”

“They’re a little group of islands north of Scotland, about the same latitude as Stockholm.”

“North of Scotland—come off it! I was stationed in Scotland during the war and the only time I ever saw the sun was through a hole in the clouds, but not often, and it was cold enough to freeze the—”

“I’m sure of it, but that was in the twentieth century. We’re now in the eleventh and in the middle of something called the Little Climactic Optimum. At least that’s what the Prof called it and if you want to know more ask him. The weather was—or is—warmer, that’s what it adds up to.”

“Hard to believe,” Dallas said, looking suspiciously up at the sun as though he expected it to go out.

The house looked the same as when they had seen it last, and one of the servants was sitting by the door sharpening a knife when they drove up. He looked up startled, dropped the whetstone and ran into the house. A moment later Ottar appeared, wiping his mouth on his forearm.

“Welcome,” he shouted as the jeep braked to a stop. “Very pleased see you again. Where is Jack Daniels?”

“The language lessons seem to have worked,” Dallas said, “but they did nothing for his thirst.”

“There’s plenty to drink,” Barney reassured him. “But I want to talk to Dr. Lyn first.”

“He’s out in back,” Ottar said, then raised his voice to a bellow. “Jens—kom hingat!”[11]

Jens Lyn tramped sluggishly around a comer of the house carrying a crude wooden bucket. His legs were bare and he was caked in mud as high as his waist. He wore an indifferent sort of sacklike garment, very ragged and caught about the middle with a length of hide, while his beard and hair were shoulder length and almost as impressive as Ottar’s. When he saw the jeep he stopped dead, his eyes widening, then shouted a harsh cry, raised the bucket over his head and ran toward them. Dallas jumped out of the jeep to face him.

“Hold it, Doc,” he said. “Put the pail down before someone gets hurt.”

The words or the stunt man’s waiting figure penetrated Lyn’s anger and he slowed to a halt, lowering the bucket. “What went wrong?” he asked loudly. “Where have you been?”

“Getting the production rolling, what else?” Barney said. “It’s only been a couple of days since I dropped you, for us that is, though I realize that for you it has been two months—”

“Two months!” Jens bellowed, “it’s been over a year! What went wrong?”

Barney shrugged. “I guess the Prof made a mistake. All those instruments, you know…”

Jens Lyn grated his teeth together so hard that the sound could clearly be heard across the intervening space. “A mistake… that’s all it is to you. While I’ve been stranded here with these louse-ridden barbarians, taking care of their filthy animals. Five minutes after you were gone Ottar hit me in the side of the head, took all my clothes and supplies and all the whiskey.”

“Why work for whiskey when it just there to take it,” Otta

r said with simple Viking logic.

“What’s done is done,” Barney said. “You’ve served your year here, but I’ll see you don’t suffer for it. Your contract is still valid and you’ll get a full year’s pay. That’s not bad money for a couple of days’ work, and you still have your sabbatical coming up and a full year’s pay for that. You did your job and taught Ottar English…”

“His thirst did that. He was repellently drunk for almost a month and when he recovered he remembered about the English lessons. He made me teach him every day so he could get some whiskey if you ever returned.”

“Ottar speak pretty good, that’s right. Where’s whiskey?”

“We have plenty, Ottar, just relax,” Barney said, then turned back to Jens, thoughts of law suits dancing darkly in his head. “What do you say we call it even, Doc? A year’s salary for teaching Ottar English and you’re still working for us while we shoot the picture. I’m sure it’s been an interesting experience…”

“Aaaarh!”

“And one you won’t easily forget, plus the fact I bet you’ve learned a lot of Old Norse…”

“Far more than I ever wanted to know.”

“So let’s call it quits. How about it?”

Jens Lyn stood for a long moment, fists clenched, then he dropped the bucket and savagely kicked it to pieces.

“All right,” he said. “Not that I have much choice. But I don’t do one moment’s work until I have a shower, a delousing and a change of clothes.”

“Sure, Doc. Well drive you back to the company in a few minutes, we’re right around the headland…”

“I’ll find it myself if you don’t mind,” he said, stamping off down the beach.

“Whiskey,” Ottar said.

“Work,” Barney told him. “If you’re on a whiskey salary you’re going to earn it. This picture starts rolling tomorrow and I want some information from you first.”

“Sure. Come in house.”

“Not on your life,” Barney said, shying away. “I remember what happened to the last guy who did that.”

8

“Stand still,” Gino shouted. “All you got to do is stand still and you can’t even do that.”

“Need a drink,” Ottar grumbled, and petulantly shook the housecarl with the matted hair who was standing in for Slithey. The man bleated and almost collapsed.

Gino swore and turned away from the viewfinder of the camera. “Barney,” he pleaded, “talk to those Stone Age slobs. This is supposed to be a love scene and they’re moving around like some kind of wrestling match on the hill there. They’re the worse stand-ins I ever worked with.”

“Just set up the shot, well be with you in a minute, Gino,” Barney said, turning back to his stars. Ruf had his arms folded, staring vacantly into space, looking very impressive indeed in the Viking outfit and blond beard. Slithey was leaning back in her safari chair while her wig was being combed, and she looked even more impressive with about twelve cubic feet of rounded flesh rising from the low-cut top of her dress.

“I’ll give it to you once more,” Barney said. “You’re in love and Ruf is leaving to go to battle and you may never see him again, so you are saying good-bye on the hill, passionately.”

“I thought I hated him?” Slithey said.

“That was yesterday,” Barney told her. “We’re not shooting in sequence, I explained this to you twice already this morning. Let me do it once more, briefly, and if I might have a small amount of your attention, too, Mr. Hawk. The picture opens when Thor, who is played by Ruf, comes with his Viking raiders to capture the farm on which you live, Slithey. You are Gudrid, the daughter of the house. In the battle all are killed by the Vikings except you, and Thor takes you as his prize. He wants you but you fight him because you hate him. But slowly he wins your heart until you fall in love with him. No sooner does this happen than he goes away on a Viking raid again and leaves you to wait for his return. That’s the scene we’re shooting now. He has left you, you run after him, you call to him, he rums and you come to him on the bill, right here. Is that clear…”

“Look,” Ruf said, pointing out to sea. “Here comes a ship.”

They all turned to look and, sure, enough, there was a Viking longship just clearing the headland and coming into the bay. The sail was furled, but the dragon’s head on the bow rose and fell as the oarsmen on each side hauled the ship through the water.

“Tomorrow!” Barney shouted. “Lyn, where are you? Didn’t you and Ottar arrange with this Finnboggi to bring his ship tomorrow?”

“They have a very loose sense of time,” Lyn said.

Barney hurled his hat to the ground and ran to the camera. “What about it, Gino?” he asked. “Is there a shot here? Anything you can get?”

Gino spun the turret to the big telescopic lens and jammed his face against the eyepiece. “Looks good,” he said, “a really nice shot.”

“Get it then, maybe we can salvage something from this.”

Ottar and the other northmen were running down the hill toward the house, nor did they stop when Barney shouted at them to keep out of the shot.

“What are they doing?” he asked, when they began to stream out, clutching weapons.

“I am sure I would not know,” Lyn told him. “Perhaps it is some custom of greeting I am not familiar with.”

Ottar and his men stood on the shore shouting and the men in the Viking ship shouted back.

“Get all this, Gino,” Barney ordered. “If it’s any good we can write it into the script.”

Under the thrust of the oars the longship ran up onto the beach, the dragon prow towering above the men waiting there. Almost before the ship had stopped moving the men aboard her had grabbed up the shields that were slung along the gunwales and jumped into the water. Like the men ashore, they also waved over their heads a varied collection of short swords and axes. The two groups met.

“How does it look?” Barney asked.

“Santa Maria!” Gino said. “They are killing each other.”

The clang of metal mingled with the hoarse cries as the men fought. No details could be made out of the turmoil by the watchers above—it was just a mass of struggling figures—until one man broke from the crowd and ran haltingly down the beach. He had been disarmed, he appeared to be wounded, and his antagonist was right behind him swinging an ax in wide circles. The chase was brief and the end was sudden. As the gap closed, the ax swooped down and the first man’s head jumped from his shoulders and bounded along the beach.

“They play for keeps…” Barney said in a choked voice.

“I do not think that this is Finnboggi and his men,” Lyn said. “I think this is a different ship that has arrived.”

Barney was a man of action, but not this kind of action. The sound of battle and the sight of the beheaded corpse and blood-drenched sand had a paralytic effect on him. What could he do? This was not his kind of world, his kind of affair. This was the kind of situation Tex or Dallas could handle. Where were they?

“The radio,” he said, belatedly remembering the transceiver slung over his shoulder; he thumbed it to life and hurriedly sent out a call for the stunt men.

“He’s seen us, he’s turning—he’s coming this way,” Gino shouted. “What a tremendous shot.”

Instead of returning to the battle, the killer was lumbering up the slope toward them, shaking the ax and calling out hoarsely. The handful of movie people on the hill watched his approach, yet did not move. This was all so alien that they could think of themselves only as onlookers, they could not imagine themselves being involved in the murderous business taking place below. The attacking Viking lumbered closer and closer, until the black marks of the ocean spray and the perspiration stains were clearly visible on the coarse red wool of his blouse—and the red spatters of blood on his ax and arm.

He went toward Gino, breathing heavily, perhaps thinking that the camera was some kind of weapon. The cameraman stayed in position until the last possible instant—filming

his enraged attacker—jumping away just as the ax came down. The blade smashed into one leg of the tripod, bending it and almost knocking the camera to the ground.

“Hey—watch out for the equipment!” Barney shouted, then regretted it instantly as the sweating, maddened Viking turned toward him.

Gino was crouched, his arm before him, with the glistening blade of a knife projecting from his fist in a very efficient manner, undoubtedly the result of his childhood training in the slums of Naples. The instant the Viking turned his attention away, Gino lunged.

The blow should have gone home but, for all his size, the Viking was as quick as a cat. He spun about and the blade slid into the slab of muscle in his side. Bellowing with sudden pain, he continued the motion, bringing up the ax so the haft caught Gino on the head, knocking him sprawling. Still shouting angrily, the man seized Gino by the hair, twisting his head down so his neck was taut and bared, at the same time raising the ax for a decaptitating blow.

The shot made a clear, hard sound and the Viking’s body jerked as the bullet caught him in the chest. He turned, mouth open with voiceless pain, and Tex—they had not even been aware the jeep had driven up—steadied his hand on the steering wheel and fired the revolver twice more. Both bullets hit the Viking in the forehead and he collapsed, dead before he hit the ground.

Gino pushed the man’s lifeless weight off his legs and stood up, shakily, going at once to the camera. Tex started the jeep’s engine again. The others were still too stunned by the suddenness of the attack to move.

“You want me to go down there and give our extras a hand?” Tex asked, pushing fresh cartridges into his gun.

“Yes,” Barney said. “We have to stop this mess before any more people are killed.”

“I can’t guarantee that won’t happen,” Tex suggested ominously, and started the jeep down the hill.

“Cut,” Barney called out to the cameraman. “We can fit a lot of things into this film—but not jeeps.”

Tex had jammed something into the button so that the horn blared continuously, and kept the gears in compound low so that the gear box screeched and the motor roared. At a bumpy five miles an hour he raced toward the battle.

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

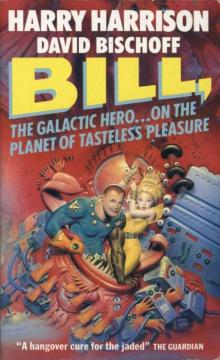

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures