- Home

- Harry Harrison

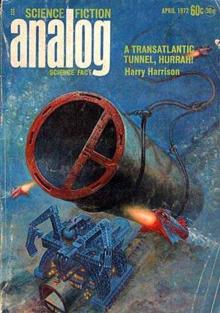

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Page 6

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Read online

Page 6

"A fine sunny morning, sir, bit of cloud about but nothing to really speak of."

The steward flicked back the curtain so that a beam of molten sunlight struck into the cabin. With professional skill he pulled open the drawer on the night table and put the tray with the cup of tea upon it. At the same time he dropped the ship's newspaper onto Washington's chest so that he awoke and blinked his eyes open just as the door closed silently behind the man. He yawned as the paper drew his attention so that he glanced through the headlines. HUNDREDS FEARED DEAD IN PERUVIAN EARTHQUAKE. SHELLING REPORTED AGAIN ALONG THE RHINE.

NEW YORK CITY WELCOMES CAESAR CHAVEZ. The paper was prepared at the line's offices in New York, he knew that, then sent by radiocopy to the airship. The tea was strong and good and he had slept well. Yet there was a sensation of something amiss, a stiffness on the side of his face and he had just touched it and found a bandage there when the door was thrown open and a short, round man dressed in black and wearing a dog collar was projected through the doorway like a human cannonball, with Wing Commander Mason close behind him.

"Oh my goodness, goodness gracious," said the spherical man, clasping and unclasping his fingers, touching the heavy crucifix he wore about his neck, then tapping the stethoscope he wore over it as though unsure whether God or Aesculapius would be of most help. "Goodness! I meant to tell the steward, dozed off, thousand pardons. Best you rest, sure of that, sleep the mender—for you not me, of course. May I?" Even as he spoke the last he touched Gus's lower eyelid with a gentle finger and pulled it down, peering inside with no less concern and awe than he would have if the owner's eternal soul had rested there.

From confusion Gus's thoughts skipped instantly to dismay, followed thereafter by a sensation of fear that sent his heart bounding and brought an instant beading of perspiration to his brow. "Then it was no dream, no nightmare," he breathed aloud. "It really happened."

The ship's commander closed the door behind him and, once secrecy was assured, he nodded gravely.

"It did indeed, Captain Washington. Though as to what happened we cannot be sure and it is my fondest wish that you enlighten me, if you can, as soon as possible. I can tell you only that the fire alarm sounded in the port engine room at 0011 hours Greenwich Mean Time. The first engineer, who was attending an engine in the starboard engine room at the time, responded instantly. He reports he found you alone and unconscious on the deck, dressed as you are now, with lacerations on your face, lying directly below the fire alarm. Pieces of glass in your wounds indicate you set off the alarm with your head and this was necessitated by the fact that your ankles and wrists were secured by handcuffs. An access door in the deck nearby was open. That is all we know. The engineer, who was wearing breathing equipment, gave you his oxygen and pulled you from the room. The Bishop of Botswana, this gentleman here, who is a physician, was called and he treated you. The manacles were cut from you and, under the bishop's direction, you were permitted to sleep. That is all we know. I hope that you will be able to tell us more."

"I can," Gus said, and his voice was hoarse. The two intent men then saw his calm, almost uncomprehending expression change to one that appeared to be that of utter despair, so profound that the priestly physician sprang forward with a cry only to be restrained by the raised hand of his patient who waved him back, at the same time drawing in a deep breath that had the hollow quality of a moan of pain, then exhaling it in what could only be a shuddering sigh.

"I remember now," he said. "I remember everything. I have killed a man."

There was absolute silence as he spoke, haltingly at first as he attempted to describe his confusion upon awakening in distress, faster and faster as he remembered the struggle in the dark, the capture, the last awful moments when another had vanished into eternity and the possibility of his own death had overwhelmed him. When he had done there were tears in the bishop's eyes, for he was a gentle man who had led a sheltered life and was a stranger to violence, while next to him the captain's eyes held no tears but instead a look of grim understanding.

"You should not blame yourself, there should be no remorse," Wing Commander Mason said, almost in the tones of a command. "The attempted crime is unspeakable. That you fought against it in self-defense is to be commended not condemned. Had I been in the same place I hope my strength of endeavor and courage would have permitted me to do the same."

"But it was I, not you, Captain. It is something I shall never forget, it is a scar I shall always carry."

"You cannot blame yourself," said the bishop, at the same time fumbling for his watch and Gus's wrist in sudden memory of his medical capacity.

"It is not a matter of blame but rather one of realization. I have done a terrible thing and the fact that it appears to be justified makes it none the less terrible."

"Yes, yes, of course," said Wing Commander Mason, a little gruffly, tugging at his beard at the same time. "But I am afraid we must carry this investigation somewhat further. Do you know who the men were—and what their possible motive might be?"

"I am as mystified as you. I have no enemies I know of."

"Did you note any distinguishing characteristics of either of them? Some tone of voice or color of hair?"

"Nothing. They were dressed in black, masked, wore gloves, did not speak but went about this business in complete silence."

"Fiends!" the bishop cried, so carried away in his emotions that he crossed himself with his stethoscope.

"But, wait, wait, the memory is there if I can only grasp it. Something, yes—a mark, blue, perhaps a tattoo of some kind. One of the men, it was on his wrist, almost under my nose where he held me, revealed when his glove moved away from his jacket, on the inner side of his wrist. I can remember no details, just blue of some kind."

"Which man?" asked the captain. "The survivor or the other?"

"That I don't know. You can understand this was not my first concern."

"Indeed. Then there is a fifty-fifty chance that the man is still aboard—if he did not follow his accomplice through the opening. But by what excuse can we examine the wrists of the passengers? The crew members are well known to us but—" He was silent on the instant, struck by some thought that darkened his face and brought upon it a certain grimness unremarked before. When he spoke again it was in the tones of absolute command.

"Captain Washington, please remain here quietly. The doctor will tend your needs and I ask you to do as he directs. I will be back quite soon."

He was gone without any more explanation and before they could request one. The bishop examined Washington more thoroughly, pronounced him fit, though exhausted, and recommended a soothing draught which was refused kindly but firmly. Washington for his part lay quietly, his face set, thinking of what he had done and of what his future life might be like with a crime of this magnitude in his memory. He would have to accept it, he realized that, and learn to live with it. In the minutes that he lay there, before the door opened again, he had matured and grown measurably older so that it was almost a new individual who looked up when the captain entered for the second time. There was a bustle behind him as the first engineer, Alec, and the second officer came in, each holding firmly to the white-clad arm of a cook.

He could be nothing else, a tall and solid man all in white, chef's hat rising high on his head, sallow skinned and neat moustachioed with a look of perplexity on his features. As soon as the door had been closed, the tiny cabin was crowded to suffocation with this mixed company, the captain spoke.

"This is Jacques, our cook, who has served with this ship since her commissioning and has been with the Cunard ten years or more. He knows nothing of the events of last night and is concerned now only with the croissants he left to burn in the oven. But he has served me many times at table and I do recall one thing."

In a single swift motion the captain seized the cook's right arm, turning it outwards and pulling back his coat. There, on the inside of his forearm and startlingly clear against the paleness of his s

kin, was a blue tattoo of anchors and ropes, trellised flowers and recumbent mermaids. Washington saw it and saw more as memory clothed the man with black instead of white, felt the strength of gloved hands again and heard the hoarseness of his breathing. Despite the bishop's attempt to prevent him he rose from the bed and stood facing the man, his face mere inches away from the other's.

"This is the one. This is the man who attempted to kill me."

For long seconds the shocked expression remained on the cook's features, a study in alarm, confusion, searching his accuser's face for meaning while Washington stared grimly and unswervingly into the other's eyes as though he were probing his soul. Then the two officers who held the man felt his arms tremble, felt his entire body begin to shake as despair seized him and replaced all else, so that instead of restraining him they found they had to support him, and when the first words broke from his lips they released a torrent of others that could not be stopped.

"Yes, I . . . I was there, but I was forced, not by choice, dear God as a witness not by choice. Sucre Dieu! And remember, you fell unconscious, I could have done as I had been bid, you could not have resisted, I saved your life, left you there. Do not let them take mine, I beg of you, it was not by choice that I did any of this—"

In his release it all came out, the wretched man's history since he had first set foot in England twenty years previously, as well as what his fate had been since. An illegal emigre, helped by friends to escape the grinding unemployment of Paris, friends who eventually turned out to be less than friends, none other than secret agents of the French crown. It was a simple device, commonly used, and it never failed. A request for aid that could not be refused—or he would be revealed to the English authorities and jailed, deported. Then more and more things to do while a record was kept of each, and they were illegal for the most part, until he was bound securely in a web of blackmail. Once trapped in the net he was rarely used after that, a sleeper as it is called in the filthy trade, resting like an inactivated bomb in the bosom of the country that had given him a home, ready to be sparked into ignition at any time. And then the flame.

An order, a meeting, a passenger on this ship, threats and humiliations as well as the revelation that his family remaining in France would be in jeopardy if he dared refuse. He could not. The midnight meeting and the horrible events that followed. Then the final terrible moment when the agent had gone and he knew that he could not commit this crime by himself.

Washington listened and understood, and it was at his instruction that the broken man was taken away—because he understood only too well. It was later, scant minutes before the flying ship began her final approach to the Narrows and a landing in New York Harbor that the captain brought Washington the final report.

"The other man is the real mystery, though it appears he was not French. A professional at this sort of thing, no papers in his luggage, no makers' marks on his clothes, an absolute blank. But he was British, everyone who spoke to him is sure of that, and had great influence or he would not be aboard this flight. All the details have been sent to Scotland Yard and the New York Police are standing by now at the dock. It is indeed a mystery. You have no idea who your enemies might be?"

Washington sealed his last bag and dropped wearily into the chair.

"I give you my word, Captain, that until last night I had no idea I had any enemies, certainly none who could work in liaison with the French secret service and hire underground operatives." He smiled wryly. "But I know it now. I certainly know it now."

VI.

A truck had gone out of control on Third Avenue and, after caroming from one of the elevated railway pillars, mounting the curb and breaking off a water hydrant, it had turned on its side and spilled its cargo out into the street. This consisted of many bundles of varicolored cloth which had split and spread a gay bunting in all directions. The workings of chance had determined that the site of the accident could not have been better chosen for the machinations of mischief, or more ill chosen for the preserving of law and order, for the event had occurred directly in front of an Iroquois bar and grill.

The occupants of the bar now poured into the street to see the fun, whooping happily through the streaming water and tearing at the bundles to see what they contained. Most of the copper-skinned men were bare above the waist, it being a warm summer day, clad only in leggings and moccasins below with perhaps a headband and feather above. They pulled out great streamers of the cloth and wrapped it about themselves and laughed uproariously while the dazed truck driver hung out of the window of his cab above and shook his fist at them.

The fun would have ended with this and there would have been no great mischief done if this establishment, The Laughing Water, had not been located just two doorways away from Clancy's, a drinking palace of the same order that drew its custom solely from men of Hibernean ancestry. This juxtaposition had caused much anguish to the police and the peace of the area in the past and was sure to do so in the future, and in fact promised to accomplish the same results now in the present.

The Irishmen, hearing the excitement, also came out into the street and stood making comments and pointing and perhaps envying the natural exuberance of the Indians'. The results were predictable and within the minute someone had been tripped, a loud name had been called, blows exchanged and a general melee resulted. The Iroquois, forced by law to check tomahawks and scalping knives at the city limits, or leave them at home if they were residents, found a ready substitute in the table knives from the grill. The Irish, equally restricted in the public display of shillelaghs, and blackthorn sticks above a certain weight, found bottles and chair legs a workable substitute and joined the fray. War whoops mixed with the names of saints and the Holy Family as they clashed.

There were no deaths or serious maimings, since the object of the exercise was pleasure, but there were certainly broken heads and bones and at least one scalp taken, the token scalp of a bit of skin and hair. The roar of a passing el train drowned the happy cries and when it had rumbled into oblivion police sirens took its place. Spectators stood at a respectable distance and enjoyed the scene while barrow merchants, quick to seize the opportunity, plied the edge of the crowd selling refreshments. It was all quite enjoyable.

Ian Macintosh found it highly objectionable, not the sort of thing at all that one would ever see on the streets of Campbelltown, or in Machrihanish. People who gave Highlanders a bad name for fighting and carousing ought to see the Colanies first. He sniffed loudly, an act easily done since his sniffer was a monolithic prow seemingly designed for that or some more important function. It was the dominating element of Macintosh's features, nay of his entire body for he was slight and narrow and dressed all in gray as he thought this only properly fitting, and his hair was gray while even his skin, when not exposed to the elements for too long a time, also partook of that neutral color. So it was his nose that dominated and due to its prominence, and to his eager attention to details and to bookkeeping, his nickname of "Nosey" might seem to be deserved, though it was never spoken before his face, or rather before his nose.

Now he hurried by on Forty-second Street, crossing Third Avenue and sniffing one parting sniff in the direction of the melee. He pressed on through the throng, dodging skillfully even as he drew out his pocket watch and consulted it. On time, of course, on time. He was never late. Even for so distasteful a meeting as this one. What must be done must be done. He sniffed again as he pushed open the door of the Commodore Hotel, quickly before the functionary stationed there could reach it, driving him back with another sniff in case he should be seeking a gratuity for a service not performed. It was exactly two o'clock when he entered and he took some grudging pleasure from the fact that Washington was already there. They shook hands, for they had met often before, and Macintosh saw for the first time the bandages on the side of the other's face that had been turned away from him until then. Gus was aware of the object of the other's attention and spoke before the question could be as

ked.

"A recent development, Ian. I'll tell you in the cab."

"No cab. Sir Winthrop is sending his own car, as well he might, though it's no pleasure riding in a thing that color."

"A car need not necessarily be black," Gus said, amused, as they went up the steps to the elevated Park Avenue entrance where the elongated yellow form of the Cord Landau was waiting. Its chrome exhausts gleamed, the wire wheels shone, the chauffeur held the door for them. Once inside, with the connecting window closed, Gus explained what had happened on the airship. "And that's the all of it," he concluded. "The cook knows nothing more and the police do not know the identity of his accomplice, or who might have employed him."

Macintosh snorted loudly, a striking sound in so small an enclosure, then patted his nose as though commending it for a good performance. "They know who did it and we know who did it, though proving it is another matter."

"But I'm sure I don't know." Gus was startled by the revelation. "You're an engineer, Augustine, and more of an engineer than I'll ever be, but you've had your head buried in the tunnel and you've no' been watching the business end, or the Stock Exchange, or the Bourse."

"I don't follow."

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

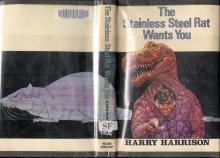

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

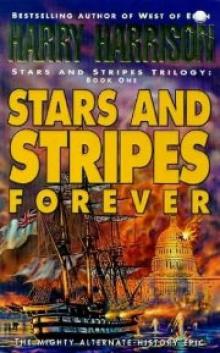

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

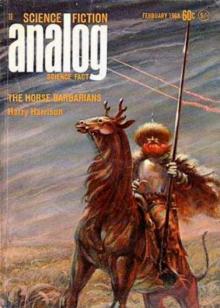

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

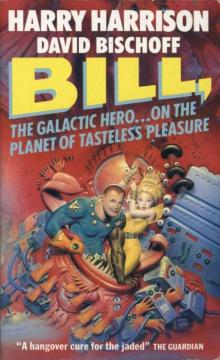

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures