- Home

- Harry Harrison

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Page 5

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Read online

Page 5

“Stop!” I thundered before he got so far in that he couldn’t back out. “I said your ancestors sent me as emissary—I am not one of your ancestors. Do not try to harm me or the wrath of those who have Passed On will turn against you.”

When I said this, I turned to jab a claw at the other priests, using the motion to cover my flicking a coin grenade toward them. It blew a nice hole in the floor with a great show of noise and smoke.

The First Lizard knew I was talking sense then and immediately called a meeting of the shamans. It, of course, took place in the public bathtub and I had to join them there. We jawed and gurgled for about an hour and settled all the major points.

I found out that they were new priests; the previous ones had all been boiled for letting the Holy Waters cease. They found out I was there only to help them restore the flow of the waters. They bought this, tentatively, and we all heaved out of the tub and trickled muddy paths across the floor. There was a bolted and guarded door that led into the pyramid proper. While it was being opened, the First Lizard turned to me.

“Undoubtedly you know of the rule,” he said. “Because the old priests did pry and peer, it was ruled henceforth that only the blind could enter the Holy of Holies.” I’d swear he was smiling, if thirty teeth peeking out of what looked like a crack in an old suitcase can be called smiling.

He was also signaling to him an underpriest who carried a brazier of charcoal complete with red-hot irons. All I could do was stand and watch as he stirred up the coals, pulled out the ruddiest iron and turned toward me. He was just drawing a bead on my right eyeball when my brain got back in gear.

“Of course,” I said, “blinding is only right. But in my case you will have to blind me before I leave the Holy of Holies, not now. I need my eyes to see and mend the Fount of Holy Waters. Once the waters flow again, I will laugh as I hurl myself on the burning iron.”

* * * * *

He took a good thirty seconds to think it over and had to agree with me. The local torturer sniffled a bit and threw a little more charcoal on the fire. The gate crashed open and I stalked through; then it banged to behind me and I was alone in the dark.

But not for long—there was a shuffling nearby and I took a chance and turned on my flash. Three priests were groping toward me, their eye-sockets red pits of burned flesh. They knew what I wanted and led the way without a word.

A crumbling and cracked stone stairway brought us up to a solid metal doorway labeled in archaic script MARK III BEACON—AUTHORIZED PERSONNEL ONLY. The trusting builders counted on the sign to do the whole job, for there wasn’t a trace of a lock on the door. One lizard merely turned the handle and we were inside the beacon.

I unzipped the front of my camouflage suit and pulled out the blueprints. With the faithful priests stumbling after me, I located the control room and turned on the lights. There was a residue of charge in the emergency batteries, just enough to give a dim light. The meters and indicators looked to be in good shape; if anything, unexpectedly bright from constant polishing.

I checked the readings carefully and found just what I had suspected. One of the eager lizards had managed to open a circuit box and had polished the switches inside. While doing this, he had thrown one of the switches and that had caused the trouble.

* * * * *

Rather, that had started the trouble. It wasn’t going to be ended by just reversing the water-valve switch. This valve was supposed to be used only for repairs, after the pile was damped. When the water was cut off with the pile in operation, it had started to overheat and the automatic safeties had dumped the charge down the pit.

I could start the water again easily enough, but there was no fuel left in the reactor.

I wasn’t going to play with the fuel problem at all. It would be far easier to install a new power plant. I had one in the ship that was about a tenth the size of the ancient bucket of bolts and produced at least four times the power. Before I sent for it, I checked over the rest of the beacon. In 2000 years, there should be some sign of wear.

The old boys had built well, I’ll give them credit for that. Ninety per cent of the machinery had no moving parts and had suffered no wear whatever. Other parts they had beefed up, figuring they would wear, but slowly. The water-feed pipe from the roof, for example. The pipe walls were at least three meters thick—and the pipe opening itself no bigger than my head. There were some things I could do, though, and I made a list of parts.

The parts, the new power plant and a few other odds and ends were chuted into a neat pile on the ship. I checked all the parts by screen before they were loaded in a metal crate. In the darkest hour before dawn, the heavy-duty eye dropped the crate outside the temple and darted away without being seen.

I watched the priests through the pryeye while they tried to open it. When they had given up, I boomed orders at them through a speaker in the crate. They spent most of the day sweating the heavy box up through the narrow temple stairs and I enjoyed a good sleep. It was resting inside the beacon door when I woke up.

* * * * *

The repairs didn’t take long, though there was plenty of groaning from the blind lizards when they heard me ripping the wall open to get at the power leads. I even hooked a gadget to the water pipe so their Holy Waters would have the usual refreshing radioactivity when they started flowing again. The moment this was all finished, I did the job they were waiting for.

I threw the switch that started the water flowing again.

There were a few minutes while the water began to gurgle down through the dry pipe. Then a roar came from outside the pyramid that must have shaken its stone walls. Shaking my hands once over my head, I went down for the eye-burning ceremony.

The blind lizards were waiting for me by the door and looked even unhappier than usual. When I tried the door, I found out why—it was bolted and barred from the other side.

“It has been decided,” a lizard said, “that you shall remain here forever and tend the Holy Waters. We will stay with you and serve your every need.”

A delightful prospect, eternity spent in a locked beacon with three blind lizards. In spite of their hospitality, I couldn’t accept.

“What—you dare interfere with the messenger of your ancestors!” I had the speaker on full volume and the vibration almost shook my head off.

The lizards cringed and I set my Solar for a narrow beam and ran it around the door jamb. There was a great crunching and banging from the junk piled against it, and then the door swung free. I threw it open. Before they could protest, I had pushed the priests out through it.

The rest of their clan showed up at the foot of the stairs and made a great ruckus while I finished welding the door shut. Running through the crowd, I faced up to the First Lizard in his tub. He sank slowly beneath the surface.

“What lack of courtesy!” I shouted. He made little bubbles in the water. “The ancestors are annoyed and have decided to forbid entrance to the Inner Temple forever; though, out of kindness, they will let the waters flow. Now I must return—on with the ceremony!”

The torture-master was too frightened to move, so I grabbed out his hot iron. A touch on the side of my face dropped a steel plate over my eyes, under the plastiskin. Then I jammed the iron hard into my phony eye-sockets and the plastic gave off an authentic odor.

A cry went up from the crowd as I dropped the iron and staggered in blind circles. I must admit it went off pretty well.

* * * * *

Before they could get any more bright ideas, I threw the switch and my plastic pterodactyl sailed in through the door. I couldn’t see it, of course, but I knew it had arrived when the grapples in the claws latched onto the steel plates on my shoulders.

I had got turned around after the eye-burning and my flying beast hooked onto me backward. I had meant to sail out bravely, blind eyes facing into the sunset; instead, I faced the crowd as I soared away, so I made the most of a bad situation and threw them a snappy military salute. Then I was out in

the fresh air and away.

When I lifted the plate and poked holes in the seared plastic, I could see the pyramid growing smaller behind me, water gushing out of the base and a happy crowd of reptiles sporting in its radioactive rush. I counted off on my talons to see if I had forgotten anything.

One: The beacon was repaired.

Two: The door was sealed, so there should be no more sabotage, accidental or deliberate.

Three: The priests should be satisfied. The water was running again, my eyes had been duly burned out, and they were back in business. Which added up to—

Four: The fact that they would probably let another repairman in, under the same conditions, if the beacon conked out again. At least I had done nothing, like butchering a few of them, that would make them antagonistic toward future ancestral messengers.

I stripped off my tattered lizard suit back in the ship, very glad that it would be some other repairman who’d get the job.

ARM OF THE LAW (1959)

At one time—this was before the Robot Restriction Laws—they’d even allowed them to make their own decisions….

It was a big, coffin-shaped plywood box that looked like it weighed a ton. This brawny type just dumped it through the door of the police station and started away. I looked up from the blotter and shouted at the trucker’s vanishing back.

“What the hell is that?”

“How should I know?” he said as he swung up into the cab. “I just deliver, I don’t X-ray ‘em. It came on the morning rocket from earth is all I know.” He gunned the truck more than he had to and threw up a billowing cloud of red dust.

“Jokers,” I growled to myself. “Mars is full of jokers.”

When I went over to look at the box I could feel the dust grate between my teeth. Chief Craig must have heard the racket because he came out of his office and helped me stand and look at the box.

“Think it’s a bomb?” he asked in a bored voice.

“Why would anyone bother—particularly with a thing this size? And all the way from earth.”

He nodded agreement and walked around to look at the other end. There was no sender’s address anywhere on the outside. Finally we had to dig out the crowbar and I went to work on the top. After some prying it pulled free and fell off.

That was when we had our first look at Ned. We all would have been a lot happier if it had been our last look as well. If we had just put the lid back on and shipped the thing back to earth! I know now what they mean about Pandora’s Box.

But we just stood there and stared like a couple of rubes. Ned lay motionless and stared back at us.

“A robot!” the Chief said.

“Very observant; it’s easy to see you went to the police academy.”

“Ha ha! Now find out what he’s doing here.”

I hadn’t gone to the academy, but this was no handicap to my finding the letter. It was sticking up out of a thick book in a pocket in the box. The Chief took the letter and read it with little enthusiasm.

“Well, well! United Robotics have the brainstorm that … robots, correctly used will tend to prove invaluable in police work … they want us to co-operate in a field test … robot enclosed is the latest experimental model; valued at 120,000 credits.”

We both looked back at the robot, sharing the wish that the credits had been in the box instead of it. The Chief frowned and moved his lips through the rest of the letter. I wondered how we got the robot out of its plywood coffin.

Experimental model or not, this was a nice-looking hunk of machinery. A uniform navy-blue all over, though the outlet cases, hooks and such were a metallic gold. Someone had gone to a lot of trouble to get that effect. This was as close as a robot could look to a cop in uniform, without being a joke. All that seemed to be missing was the badge and gun.

Then I noticed the tiny glow of light in the robot’s eye lenses. It had never occurred to me before that the thing might be turned on. There was nothing to lose by finding out.

“Get out of that box,” I said.

The robot came up smooth and fast as a rocket, landing two feet in front of me and whipping out a snappy salute.

“Police Experimental Robot, serial number XPO-456-934B, reporting for duty, sir.”

His voice quivered with alertness and I could almost hear the humming of those taut cable muscles. He may have had a stainless steel hide and a bunch of wires for a brain—but he spelled rookie cop to me just the same. The fact that he was man-height with two arms, two legs and that painted-on uniform helped. All I had to do was squint my eyes a bit and there stood Ned the Rookie Cop. Fresh out of school and raring to go. I shook my head to get rid of the illusion. This was just six feet of machine that boffins and brain-boys had turned out for their own amusement.

“Relax, Ned,” I said. He was still holding the salute. “At ease. You’ll get a hernia of your exhaust pipe if you stay so tense. Anyways, I’m just the sergeant here. That’s the Chief of Police over there.”

Ned did an about face and slid over to the Chief with that same greased-lightning motion. The Chief just looked at him like something that sprang out from under the hood of a car, while Ned went through the same report routine.

“I wonder if it does anything else beside salute and report,” the Chief said while he walked around the robot, looking it over like a dog with a hydrant.

“The functions, operations and responsible courses of action open to the Police Experimental Robots are outlined on pages 184 to 213 of the manual.” Ned’s voice was muffled for a second while he half-dived back into his case and came up with the volume mentioned. “A detailed breakdown of these will also be found on pages 1035 to 1267 inclusive.”

The Chief, who has trouble reading an entire comic page at one sitting, turned the 6-inch-thick book over in his hands like it would maybe bite him. When he had a rough idea of how much it weighed and a good feel of the binding he threw it on my desk.

“Take care of this,” he said to me as he headed towards his office. “And the robot, too. Do something with it.” The Chief’s span of attention never was great and it had been strained to the limit this time.

I flipped through the book, wondering. One thing I never have had much to do with is robots, so I know just as much about them as any Joe in the street. Probably less. The book was filled with pages of fine print, fancy mathematics, wiring diagrams and charts in nine colors and that kind of thing. It needed close attention. Which attention I was not prepared to give at the time. The book slid shut and I eyed the newest employee of the city of Nineport.

“There is a broom behind the door. Do you know how to use it?”

“Yes, sir.”

“In that case you will sweep out this room, raising as small a cloud of dust as possible at the same time.”

He did a very neat job of it.

I watched 120,000 credits worth of machinery making a tidy pile of butts and sand and wondered why it had been sent to Nineport. Probably because there wasn’t another police force in the solar system that was smaller or more unimportant than ours. The engineers must have figured this would be a good spot for a field test. Even if the thing blew up, nobody would really mind. There would probably be someone along some day to get a report on it. Well, they had picked the right spot all right. Nineport was just a little bit beyond nowhere.

Which, of course, was why I was there. I was the only real cop on the force. They needed at least one to give an illusion of the wheels going around. The Chief, Alonzo Craig, had just enough sense to take graft without dropping the money. There were two patrolmen. One old and drunk most of the time. The other so young the only scar he had was the mark of the attram. I had ten years on a metropolitan force, earthside. Why I left is nobody’s damn business. I have long since paid for any mistakes I made there by ending up in Nineport.

Nineport is not a city, it’s just a place where people stop. The only permanent citizens are the ones who cater to those on the way through. Hotel keepers, restaurant owners,

gamblers, barkeeps, and the rest.

There is a spaceport, but only some freighters come there. To pick up the metal from some of the mines that are still working. Some of the settlers still came in for supplies. You might say that Nineport was a town that just missed the boat. In a hundred years I doubt if there will be enough left sticking of the sand to even tell where it used to be. I won’t be there either, so I couldn’t care less.

I went back to the blotter. Five drunks in the tank, an average night’s haul. While I wrote them up Fats dragged in the sixth one.

“Locked himself in the ladies’ john at the spaceport and resisting arrest,” he reported.

“D and D. Throw him in with the rest.”

Fats steered his limp victim across the floor, matching him step for dragging step. I always marveled at the way Fats took care of drunks, since he usually had more under his belt than they had. I have never seen him falling down drunk or completely sober. About all he was good for was keeping a blurred eye on the lockup and running in drunks. He did well at that. No matter what they crawled under or on top of, he found them. No doubt due to the same shared natural instincts.

Fats clanged the door behind number six and weaved his way back in. “What’s that?” he asked, peering at the robot along the purple beauty of his nose.

“That is a robot. I have forgotten the number his mother gave him at the factory so we will call him Ned. He works here now.”

“Good for him! He can clean up the tank after we throw the bums out.”

“That’s my job,” Billy said coming in through the front door. He clutched his nightstick and scowled out from under the brim of his uniform cap. It is not that Billy is stupid, just that most of his strength has gone into his back instead of his mind.

“That’s Ned’s job now because you have a promotion. You are going to help me with some of my work.”

Billy came in very handy at times and I was anxious that the force shouldn’t lose him. My explanation cheered him because he sat down by Fats and watched Ned do the floor.

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

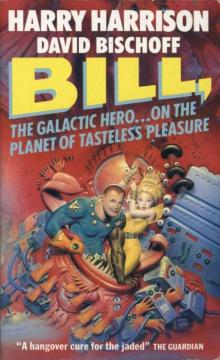

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures