- Home

- Harry Harrison

Make Room! Make Room! Page 4

Make Room! Make Room! Read online

Page 4

When he turned into the doorway his heart thudded as he saw that the bench was empty. Mr. Burgger looked up from his desk and the anger was as fresh on his face as it had been that afternoon.

“It’s a good thing you made up your mind to come back or you just wouldn’t have had to bother coming back. Everything is moving tonight, I don’t know why. Get this delivered.” He finished scrawling an address on the cover, then slipped the gummed-paper seal through the hole in the hinged boards and licked it and sealed it shut. “Cash on the counter.” He slapped the board down.

The clip wouldn’t unbend and Billy broke a fingernail when he had to work the money out and unroll one of the bills and slide it across the scratched wood. He held tight to the other bill, clutched at the board and hurried out, stopping with his back to the wall as soon as he was out of sight of the office. There was enough light from the illuminated sign to read the address:

Michael O’Brien

Chelsea Park North

W. 28 St.

He knew the address and, though he had passed the buildings an untold number of times, he had never been inside the solid cliff of luxury apartments that had been built in 1976 after a spectacular bit of corruption had permitted the city to turn Chelsea Park over to private development. They were walled, terraced and turreted in new-feudal style, which appearance perfectly matched their function of keeping the masses as separate and distant as possible. There was a service entrance in the rear, dimly lit by a wire-caged bulb concealed in a carved stone cresset, and he pressed the button beneath it.

“This entrance is closed until oh-five hundred hours,” a recorded voice clattered at him and he held the board to his chest in a quick spasm of fear. Now he would have to go around to the front entrance with its lights, the doorman, the people there; he looked down at his bare legs and tried to brush away some of the older stains. He was clean enough now, but there was nothing he could do about the ragged and patched clothing. Normally he never noticed this because everyone else he met was dressed the same way, it was just that things were different here, he knew that. He didn’t want to face the people in this building, he regretted that he had ever worked to get this job, and he walked around the corner towards the brilliantly lit entrance.

A pondlike moat, now just a dry receptacle for rubbish, was crossed by a fixed walkway tricked out to look like a drawbridge, complete with rusty chains and a dropped portcullis of spike-ended metal bars backed by heavy glass. Walking the brightly lit path of the bridge was like walking into the jaws of hell. The bulky figure of the doorman was silhouetted behind the bars ahead, hands behind his back, and he did not move even after Billy had stopped, just inches away on the other side of the barred glass, but kept staring down at him coldly with no change of expression. The door did not open. Not trusting himself to say anything, Billy held up the message board so the name could be seen on the outside. The doorman’s eyes flicked over it and he reluctantly touched one of the decorative whorls and a section of bars and glass slid aside with a muffled sigh.

“I got a message here….” Billy was unhappily aware of the uncertainty and fear in his voice.

“Newton, front,” the doorman said and jerked his thumb at Billy to enter.

A door opened on the far side of the lobby and there was a rumble of masculine laughter, suddenly cut off as a man came out and closed the door behind him. He was dressed in a uniform like the doorman’s, deep black with gold buttons, but with only a curl of red braid on each shoulder rather than the other’s resplendent frogging. “What’s up, Charlie?” he asked.

“Kid with a telegram, I never saw him before.” Charlie turned his back on them and resumed his watchdog position before the door, his duty done.

“The board is good,” Newton said, twisting it from Billy’s grasp before he realized what was happening, and running his fingers over the indented Western Union trademark. He handed it back and when Billy took it he quickly patted his shirt and shorts, under the arms and in the crotch.

“He’s clean,” then he laughed, “except I gotta go wash my hands now.”

“All right, kid,” the doorman said without turning, his back still to Billy, “bring it up and get down here again, quick.”

The guard had his back turned too as he walked away leaving Billy alone in the center of the lobby, in the middle of the stretch of figured carpet with no sign of what to do or where to go next. He wanted to ask directions but he couldn’t, the automatic contempt and superiority of the men had disarmed him, driven him down so that all he wanted to do was find a place to hide. A gliding hiss from the far end of the room drew his numbed attention and he saw an elevator door slide open in the base of what he had taken to be a giant church organ. The operator was looking at him and Billy started forward, the telegram board held before him as though it were a shield against the hostility of the environment.

“I got a message here for Mr. O’Brien.” His voice quavered and almost cracked. The operator, a boy no older than he was, produced a half-authentic sneer; he was young but was already working hard at learning the correct staff manners.

“O’Brien, 41-E, and that’s on the fifth floor in case you don’t know anything about apartment houses.” He stood, blocking the elevator entrance, and Billy was uncertain what to do next.

“Should I … I mean, the elevator …”

“You ain’t stinking up this elevator for the tenants. The stairs are down that way.”

Billy felt the angry eyes following him as he walked down the hall and some of the anger caught in him. Why did they have to act like that? Just working in a place like this didn’t mean they lived here. That would be a laugh—them living in a place like this. Even that fat chunk of a doorman. Five flights—he was panting for breath before he had reached the second and had to stop and wipe off some of the sweat when he got to the fifth. The hall stretched away in both directions, with alcoved doors opening off of it and an occasional suit of armor standing guard over its empty length. His skin prickled with sweat; the air was breathless and hot. He started in the wrong direction and had to retrace his steps when he found out that the numbers were decreasing toward zero. Number 41-E was like all the others without a button or knocker, just a small plate with the gilt script word O’Brien on it. The door opened when he touched it and, after looking in first, he entered a small, darkly paneled chamber with another door before him; a sort of medieval airlock. He had a feeling of panic when the door closed behind him and a voice spoke, apparently from thin air.

“What do you want?”

“A telegram, Western Union,” he said and looked around the empty cubicle for the source of the voice.

“Let me see your board.”

It was then he realized that the voice was coming from a grille above the inner door, next to the glassy eye of a TV pickup. He held up the board so that it could be seen by the orthicon. This must have satisfied the unseen watcher because there was the click of the circuit going dead and shortly after that the door opened before him, letting out a wave of chilled air.

“Let me have it,” Michael O’Brien said, and Billy handed him the board and waited while the man broke the seal with his thumb and opened the hinged halves.

Though he was in his late fifties, iron gray, carrying an impressive paunch and a double row of jewels, O’Brien still bore the marks of his early years on the West Side docks. Scars on his knuckles and on the side of his neck—and a broken nose that had never been set correctly. In 1966 he had been a twenty-two-year-old punk, as he was fond of saying when he told the story, with nothing on his mind but booze and broads and a couple of days’ stevedoring a week to pay for the weekends, but when he had walked into a roundhouse swing in a brawl at the Shamrock Bar and Grill it had changed his life for him. While recovering in St. Vincent’s (the nose had healed quickly enough but he had fractured his skull on the floor) he had taken a long look at his life and decided to make something of it. What it was he made he never added when he told the sto

ry, but it was common knowledge that he had become involved with ward politics, the disposal of hijacked goods from the docks and a number of other things that were best not to mention in his hearing. In any case his new interests paid better than stevedoring and he had never regretted a moment of it. Six foot two, and swaddled in an immense and colorful dressing gown like a circus elephant, he could have been ludicrous, but wasn’t. He had seen too much, done too much, was too sure of his power ever to be laughed at—even though he moved his lips when he read and frowned in concentration while he spelled out the telegram.

“Wait there, I want to make a copy of this,” he said when he came to the end. Billy nodded, happy to wait as long as possible in the air-cooled, richly decorated hall. “Shirl, where the hell is the pad?” O’Brien shouted.

There was a mumbled answer from the door on the left and O’Brien opened it and went into the room. Billy’s eyes automatically followed him through the lit doorway to the white-sheeted bed and the woman lying there.

She lay with her back turned, unclothed, red hair sweeping across the pillow, her skin a whitish pink with a scattering of brown freckles across the shoulders. Billy Chung stood unmoving, his breath choked in his throat; she wasn’t ten feet away. She crossed one leg over the other, accentuating the round swell of buttock. O’Brien was talking to her but the words came through as meaningless sounds. Then she rolled over toward the open door and saw him.

There was nothing he could do, he could not move and he could not turn his eyes away. She saw him looking at her.

The girl on the bed smiled at him, then reached out a slender arm to the door, her breasts rose full and round, pink tipped—the door swung shut and she was gone.

When O’Brien opened the door and came out a minute later she was no longer on the bed.

“Any answer?” Billy asked as he took back the message board. Did his voice sound as strange to this man as it did to him?

“No, no answer,” O’Brien said as he opened the hall door. Time seemed to be moving slowly now for Billy, he clearly saw the door as it opened, the shining tongue of the lock, the flat piece of metal on the wall with the hanging wires. Why were these important?

“Aren’t you gonna give me a tip, mister?” he asked, just to occupy a moment more.

“Beat it, kid, before I boot your chunk.”

He was in the hall and the heat hit him doubly hard after the cool apartment, pressing on his skin and meeting the spreading warm that suffused the lower part of his body, just the kind of feeling he had the first time he got near a girl; he rested his head against the wall. Even in the pictures they passed around he had never seen a girl like this. All the ones he had banged had been glimpsed briefly in a dim light or not at all, thin limbs, gray skins, dirty as he, with ragged underclothing.

Of course. A single lock on the inner door guarded by the burglar alarm above. But the alarm was disconnected, he had seen the dangling wires. He had learned about things like this when Sam-Sam had run the Tigers, they had broken into stores and done a couple of jobs of burglary before the cops shot Sam-Sam. A sharp jimmy would open that door in a second. But what did this have to do with the girl? She had smiled, hadn’t she? She could be there waiting when the old bastard went to work.

It was a lot of crap and he knew it, the girl wouldn’t have anything to do with him. But she had smiled? The apartment was different, a quick job before the wiring was fixed, he knew the layout of the building—if only there was a way of getting by those chunkheads at the front door. This had nothing to do with the girl, this was for cash. He went quietly down the stairs, looking carefully before turning the corner on the ground floor and hurrying on to the basement.

You had to ride your luck. He didn’t meet anyone and in the second room he entered he found a window that also had a disconnected burglar alarm on it. Maybe the whole building was like that, they were rewiring it or it had broken and they couldn’t fix it, it didn’t matter. The window was covered with dust and he reached up and drew a heart in the film of dust so he could recognize it from the outside.

“You took a long time, kid,” the doorman said when he came up.

“I had to wait while he copied the message and wrote an answer, I can’t help it.” He whined the lie with unsuspected sincerity, it was easy.

The doorman didn’t ask to look at the board. With a pneumatic hiss the portcullis opened and he went across the empty drawbridge to the dark, crowded, dirty and stifling street.

3

Behind the low hum of the air-conditioner, so steady a sound that the ear accepted it and no longer heard it, was the throbbing rumble of the city outside, beating like a great pulse, more felt than heard. Shirl liked that, liked its distance and the closed-in and safe feeling the night and thickness of the walls gave her. It was late, 3:24 the glowing numbers on the clock read, then changed soundlessly to 3:25 while she watched. She shifted position and beside her in the wide bed Mike stirred and mumbled something in his sleep and she lay perfectly still, hoping he wouldn’t wake up. After a moment he settled down, pulling the sheet over his shoulders, his breathing grew slow and steady again and she relaxed. The motion of the air was drying the perspiration from her skin, a cool feeling the length of her uncovered body, strangely satisfying. Before he had come to bed and wakened her she had had a few hours’ sleep and that seemed to be enough. Moving slowly, she stood and walked over in front of the flow of air so that it washed her body in its stream. She ran her hands over her skin, wincing when they touched her sore breasts. He was always too rough and it showed on her kind of skin; she’d be black-and-blue tomorrow, then she’d have to put heavy makeup on to cover the marks. Mike got angry if he saw her with any blemishes or bruises, though he never seemed to think of that when he was hurting her. Above the air-conditioner the curtains were open a crack and the darkness of the city looked in, the widely separated lights like the eyes of animals; she quickly closed the curtains and patted them so they would stay shut.

Mike gave a deep, throaty gargle, a startling sound when you weren’t used to it, but Shirl had heard it often enough. When he snored like that it meant he was really sound asleep—maybe she could take a shower without his knowing it. Her bare feet were noiseless on the rug and she closed the bathroom door so slowly it never made a click. There! She switched on the fluorescents and smiled around at the plast-marble interior and the gold-covered fixtures with highlights glinting everywhere. The walls were sound-proof but if he wasn’t really deeply asleep he might hear the water knocking in the pipes. A sudden fear hit her and she gasped and stood on tiptoe to look at the water meter. Yes, her breath escaped in a relaxed sigh, he had turned it on. With water costing what it did Mike turned it off and locked it during the day, the help had been stealing so much, and he had forbidden her to take any more showers. But he always took showers and if she sneaked one once in a while he couldn’t tell from the dial.

It was cool and lovely and she stayed in it longer than she had meant to; she looked guiltily at the meter. After she had dried herself she used the towel to mop up every drop of water in the tub and on the walls and floor, then buried the towel in the bottom of the hamper where he would never see it. Her skin tingled and she felt wonderful. She smiled to herself as she patted on dusting powder. You’re twenty-three, Shirl, and your dress size hasn’t changed since you were nineteen. Except in the bust maybe, she was using a bigger bra, but that was all right because men liked it that way. She took a clean housecoat from the cupboard and slipped it on.

Mike was still sawing away when she passed through the bedroom, he seemed to be exhausted these days, probably tired from carrying around all that weight in this heat. In the year she had been living here he must have put on twenty pounds, most of it around the middle it looked like, but it didn’t seem to bother him and she tried not to notice it. She turned on the TV to warm up, and then went into the kitchen to make a drink. The expensive stuff, the beer and the single bottle of whiskey, were for Mike only, but she

didn’t mind, she really didn’t care what she drank as long as it tasted nice. There was a bottle of vodka, Mike could get all of that they needed, and it tasted good mixed with the orange concentrate. If you added some sugar.

A man’s head filled the fifty-inch screen mouthing unheard words, looking right out at her; she pulled the gaping front of her housecoat closed and buttoned it. She smiled at herself when she did it, as she always did, because even though she knew the man couldn’t see her it made her uncomfortable. The remote-box was on the arm of the couch and she curled up next to it with the drink and tapped the button. On the next channel was an auto race and on the next an old John Barrymore picture that looked jerky and ancient and she didn’t like it. She went through most of the channels this way until she settled, as she usually did, on Channel 19, the Woman’s Own Channel, which showed nothing but soap-opera serials, one serial at a time with all the episodes compacted together into a single great, glutinous chunk sometimes running up to twenty-four hours. This was one she hadn’t seen before and when she plugged the earphone into the remote she discovered why, it was a British serial of some kind. The people all had strange accents and some of the things they did were a little hard to follow, but it was interesting enough. A woman had just given birth, sweating and without makeup, when she tuned in and the woman’s husband was in jail but the news had come he had just escaped, and the man who was the father of the baby—a blue baby, they had just discovered—was her husband’s brother. Shirl took a sip of the drink and snuggled down comfortably.

At six o’clock she turned off the set, washed and dried her glass and went in to get her clothes. Tab came on duty at seven and she wanted to get the shopping done as early as possible, before the worst of the heat. Quietly, so as not to wake Mike, she found her clothes and took them into the living room to dress. Panties and the net bra and her gray sleeveless dress, it was old enough and faded enough to go shopping in. No jewelry and of course no makeup, there was no point in looking for trouble. She never ate breakfast, that was a good way to watch calories, but she did have a cup of black kofee before she left. It was just seven when she checked to see if her key and money were in her purse, took the big shopping bag from the drawer and let herself out.

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

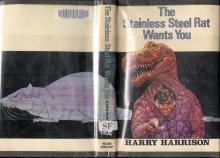

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

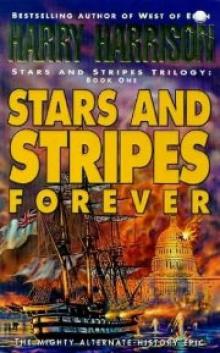

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

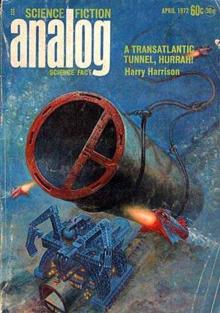

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

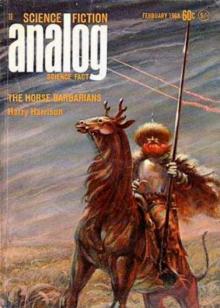

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

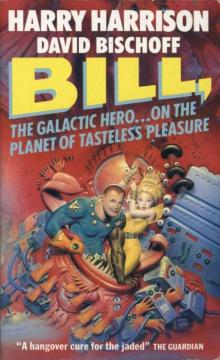

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures