- Home

- Harry Harrison

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Page 4

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Read online

Page 4

Never had the sun shone so warmly and brightly. The afternoon sun. I smiled back at it just as warmly, bereft of any guilt, filled full with happiness. Nibbling a bit of fruit and sipping some wine. Turning languidly from the window as Bibs reentered the room.

"You mean it?" she asked. "You won't go off-planet with me? You don't want to?"

"Of course I want to. But not until I have found Garth."

"He'll find you first and kill you."

"Perhaps he might be the one who gets killed."

She cocked her head most prettily to one side, then nodded. "From anyone but you I would think that bragging. But you might just do it." She sighed. "But I won't be here to see it. I rate survival ahead of vengeance. He put me into jail-you got me out. Case closed. Though I admit to a big bundle of curiosity. If you do get out of this, will you let me know what happened? A message care of the Venian Crewmembers' Union will get to me eventually." She passed over a slip of paper. "I've written down everything that I remembered, just like you asked."

"General," I read. "Either Zennor or Zennar."

"I never saw it spelled out. Just overheard one of the officers talking to him when they didn't know I could hear them."

"What is Mortstertoro?"

"A big military base, perhaps their biggest. That's where we landed to take on cargo. They wouldn't let us out of the spacer, but what we could see was very impressive. A big limousine, all flags and stars, would come for Garth and take him away. There was a lot of saluting-and they always saluted him first. He is something big, high-up, and whatever he is involved with has to do with that base. I'm sorry, I know it's not much."

"It's a lot, all I need now." I folded the paper and put it away. "What next."

"We should have identification documents by tonight. They are expensive but real. Issued by one of the smaller duchies that needs the foreign exchange. So I can ship out on any spacer I want to. As long as the League agents don't recognize me. But I've managed to bribe my way onto a trade delegation that made their flight arrangements months ago. One of them has been well paid to get lost."

"When do you leave?"

"Midnight," she said in a very quiet voice.

"No! So soon . . ."

"I felt the same way-which is why I am leaving. I am not the kind of person that gets tied down in a relationship, Jimmy."

"I don't know what you mean."

"Good. Then I am getting away before you find out." This sort of conversation was all very new and confusing. I am reluctantly forced to admit that up until the previous evening my contact with the opposite sex had been, shall we say, more distant. Now I was at an unaccustomed loss for words, indecisive and more than a little bewildered. When I blurted this out Bibs had nodded in apparent complete understanding. I realized now that there was an awful lot I did not know about women, a mountain of knowledge I might never acquire.

"My plans aren't that fixed . . ." I started to say, but she silenced me with a warm finger to my lips.

"Yes they are. And you're not going to change them on my account. You seemed very certain this morning about what you felt you had to do."

"And I am still certain," I said firmly, with more firmness and certainty than I felt. "The bribe to get me over to Nevenkebia was taken?"

"Doubled before accepted. If you are going to go missing then old Grbonja will never be permitted to go ashore there again. But he has been ready to retire for years. The bribe is just the financial cushion he needs."

"What does he do?"

"Exports fruit and vegetables. You'll go along as one of his laborers. He won't be punished if you get away from the market-but they will take away his landing pass. He won't mind."

"When do I get to see him?"

"We go to his warehouse tonight, after dark."

"Then...."

"I leave you there. Are you hungry?"

"We just ate. "

"That is not what I mean," she answered in a very husky voice.

The dark streets were lit only by occasional torches at the corners, the air heavy with menace. We walked in silence; perhaps everything that might be said had already been said. I had bought a sharp dagger which hung at my waist, and another club that I slammed against a wall occasionally to be sure any watchers knew it was there. All too soon we reached our destination, for Bibs knocked on a small gate let into a high wall. There were some whispered words and the gate creaked open. I could smell the sweetness of fruit all about us as we threaded through the dark mounds, to the lamplit corner where an elderly man slumped in a chair. He was all gray beard and gray hair to his waist, where the hair spread out over a monstrous paunch held up by spindly legs. One eye was covered by a cloth wound round his head, but the other looked at me closely as I came up.

"This is the one you are taking," Bibs said. "Does he speak Esperanto?"

"Like a native," I said.

"Give me the money now." He held out his hand.

"No. You'll just leave him behind. Ploveci will give it to you after you land."

"Let me see it then." He turned his beady eye on me and I realized that I was Ploveci. I took out the leathern bag, spread the coins out on my hands, then put them back into the bag. Grbonja grunted what I assumed was a sign of assent. I felt a breeze on my neck and wheeled about.

The gate was just closing. Bibs was gone.

"You can sleep here," he said pointing to a heap of tumbled sacks against the wall. "We load and leave at dawn."

When he left he took the lamp with him. I looked into the darkness, toward the closed gate.

I had little choice in the matter. I sat on the sacks with my back to the wall, the club across my legs and thought about what I was doing, what I had done, what we had done, what I was going to do, and about the conflicting emotions that washed back and forth through my body. This was apparently too much thinking because the next thing I knew I was blinking at the sunlight coming through the opening door, my face buried in the sacks and my club beside me on the floor. I scrambled up, felt for the money- still there-and was just about ready for what the day would bring. Yawning and stretching the stiffness from my muscles. Reluctantly.

The large door was pulled wider and I saw now that it opened onto a wharf with the fog-covered ocean beyond.

A sizable sailing vessel was tied up there and Grbonja was coming down the gangway from the deck.

"Ploveci,help them load," he ordered and passed on.

A scruffy gang of laborers followed him into the warehouse and seized up filled sacks from the pile closest to the door. I couldn't understand a word they said, nor did I need to. The work was hot, boring, and exhausting, and consisted simply of humping a sack from the warehouse to the ship, then returning for another. There was some pungent vegetable in the sacks that soon had my eyes running and itching. I was the only one who seemed to mind. There was no nonsense about breaks either. We carried the sacks until the ship was full, and only then did we drop down in the shade and dip into a bucket of weak beer. It had foul wooden cups secured to it by thongs and after a single, fleeting moment of delicacy I seized one up, filled and emptied it, filled and drank from it once again.

Grbonja reappeared, as soon as the work was done, and gurgled what were obviously orders. The longshoremen became sailors, pulled in the gangplank, let go the lines and ran up the sail. I stood to one side and fondled my club until Grbonja ordered me into the cabin and out of sight. He joined me there a few moments later. "I'll take the money now," he said.

"Not quite yet, grandpop. You get it when I am safely ashore, as agreed."

"They must not see me take it!"

"Fear not. Just stand close to the top of the gangplank and I will stumble against you. When I'm gone you will find the bag tucked into your belt. Now tell me what I will find when I get ashore."

"Trouble!" he wailed and raked his fingers through his beard. "I should never have gotten involved. They will catch you, kill you, me too . . ."

"Relax, look at thi

s." I held the money bag in the beam of light from the grating above and let the coins trickle between my fingers. "A happy retirement, a place in the country, a barrel of beer and a plate of porkchops every day, think of all the joys this will bring."

He thought and the sight of the clinking coins had great calming effect. When his fingers had stopped shaking I gave him a handful of money which he clutched happily.

"There. A down payment to show that we are friends. Now think about this-the more I know about what I will find when I get ashore the easier it will be for me to get away. You won't be involved. Now . . . speak."

"I know little," he mumbled, most of his attention on the shining coins. "There are the docks, the market behind. All surrounded by a high wall. I have never been past the wall. "

"Are there gates?"

"Yes, large ones, but they are guarded."

"Is the market very large?"

"Gigantic. It is the center of trade for the entire country. It stretches for many myldyryow along the coast."

"How big is a myldyryow?"

"Myldyr, myldyryow is plural. One of them is seven hundred lathow."

"Thanks. I'll just have to see for myself."

Grbonja, with much grunting and gasping, threw open a hatch in the deck and vanished below, undoubtedly to hide the coins I had given him. I realized then that I had had enough of the cabin so I went out on deck, up to the bow where I would not be under foot. The sun was burning off the morning haze and I saw that we were passing close to an immense tower that rose up from the water. It was scarred, ancient, certainly centuries old. They had built well in those days. The mist lifted and revealed more and more of the structure, stretching up out of sight. I had to lean back to see the top, high, high above.

With the remains of the fractured bridge hanging from it. The once-suspended roadway hung crumpled and broken, dipping down into the ocean close by. Rusted, twisted, heaped with the broken supporting cables which were over two meters thick. I wondered what catastrophe had brought it down.

Or had they destroyed it to cut themselves free from the continent that was slowly sinking back into barbarism? A good possibility. And if they had done this they showed a firmness of mind that made my penetration of their island that much more difficult.

Before I could worry about this a more immediate threat presented itself, A lean, gray ship bristling with guns came thundering up from ahead. It cut across our bow and turned sharply around our stern; our sailing ship bobbed in its wake and the sails flapped. I emulated the sailors and tried to ignore the deadly presence, the pointed weapons that could blow us out of the water in an instant. We were here on legitimate business-weren't we?

The gunboat's commander must have believed this as well because, with an insulting blare on their horn, the vessel changed course again and blasted away across the sea. When the ship had dwindled into the distance one of the sailors shook his fist after them and said something bitter and incomprehensible that I agreed with completely.

Nevenkebia rose out of the mists ahead. Cliffs and green hills backing an immense, storied city that rose up from a circular harbor. Factories and mineheads beyond, plumes of smoke from industry already busy in the early morning. And forts at the water's edge, great guns gloaming. Another fort at the end of the seawall as we entered the harbor. I could feel the glare of suspicious eyes behind the gunsights as the black mouths of the barrels followed us as we passed. These guys were not kidding.

And I was going to tackle this entire country singlehanded?

"Sure you are, Jim," I said aloud with great braggadocio, swinging my club so that it whistled in tight arcs. "You'll show them. They don't stand a chance against fighting Jimmy diGriz."

Which would have been fine if my voice had not cracked as I said it.

CHAPTER 5

"Down sails," an amplified voice roared. "Take our line aboard." A high-prowed tug came chuntering up with its loudhailer bellowing. Grbonja swiftly translated the commands to the crew.

Nothing was left to chance in Nevenkebia: all matters were highly organized. Even before the sail was down we were secured safely to the tug and being towed to our berth at the crowded wharfside. Sailing craft of interesting variety and form were already unloading cargo there. We were moved into a vacant berth among the others.

"They come long ways," Grbonja wheezed, stumbling up beside me, pointing at the other ships. "From Penpilick, Grampound, even Praze-an-Beeble-may everyone there suffer from a lifetime of dysesya! Tie up outside harbor at night. You give me the money now, too dangerous on shore!"

"A deal's a deal, grandpop. Too late to back out now. " He sweated and muttered and looked at the land coming close. "I go ahead first, talk to freightmaster. Only then we unload. They take your papers and give you dock badge. After that you will see me. Give me the money."

"No sweat. Just keep your mind on the sunny future of happy retirement."

Two armed guards glowered down at us as we tied up.

A steam winch dropped the gangway into place and Grbonja puffed up the incline and onto the dock. To turn me in? Maybe I should have paid him in advance? My heart gave a few quick thuds as it shifted into worry mode.

In a few minutes-or was it centuries?-Grbonja had returned and was shouting instructions at the crew. I left my club in the cabin and put the dagger inside my shirt where it couldn't be seen. My lockpick and remaining coins were in a pouch inside my shirt as well. I was ready as I was ever going to be. When I came out of the cabin the sailors were already staying to unload. I picked up a bag and followed the others up the gangway. Each of them held out his identity papers: I did the same. As they reached the dock the officer there took each man's papers and stuffed them into a box. Then pinned an identification tag to the man's clothes. He looked bored by the job. I tried not to tremble as I came up to him.

It was just routine. "Next," he called out, whipped the papers from my hand and pinned the tag to my chest. Or rather pinned it through the fabric into my skin. I jumped but kept my mouth shut. He grinned, with a touch of sadism in the turn of his mouth, and pushed me on. "Keep moving, lunkhead. Next."

I was safely ashore and undetected. Following the bent back of the man ahead of me into the dark warehouse. Grbonja was standing by the growing pile of sacks. When he saw me he called out an incomprehensible instruction and pointed to the next bay.

"The money, now," he burbled as I dumped the sack. I slipped it to him and he staggered away muttering with relief. I looked around at the solid cement and steel walls and went back for another sack.

By the time I had carried in my third sack I was getting desperate. After a few more trips the ship would be unloaded and that would be the end of that. I would have had an expensive round trip and done some hard Work. Nothing more. Because I could see no way out of the building-and no place to hide within, it. They obviously did not relish uninvited visitors to Nevenkebia. I needed more time.

"Call a beer break," I whispered to Grbonja as I passed him at the head of the gangway. The checker-inner had gone but the two unsmiling guards still stood watch. "We never stop-it is not the custom."

"It is today. It's a hot day. You don't want me to tell them you were hired to smuggle me here?"

He groaned aloud, then called out. "Beer, we stop for beer!"

The crew asked no questions at this unexpected treat, only chattered together with pleasure as they gathered round the barrel. I had a good slug of the stuff then went and sat on the gunwhale beside the gangway. Looked up at the boots of the guard who stood above me. Looked down at the water and saw the space between the pilings there.

My only chance. The guard above me moved out of sight. Grbonja had his back turned while the sailors had their attention focused on the barrel. A difference of opinion over the rationing appeared to breakout. There were angry shouts and a quick blow. The crew watched these proceedings with great interest. No one was visible on the dock above.

I dropped a length of line over the sid

e, swung my legs over and climbed down it. No one saw me go. With my legs in the sea I used my dagger to cut the line above my head and dropped silently into the water. With noiseless strokes I swam into the darkness under the pier.

Slime-covered boards connected the wooden piles. When I reached for one of them something squealed and vanished in the darkness. And it stank down here. Nameless rubbish bobbed in the water around me. I was beginning to regret my impetuous swim.

"Chin up, Jim, and move along. This is the first place they look when they find out you are missing." I swam. Not far, for there was a solid wall here that ran back into the darkness. I groped along it until I reached the outer piles again. Through the openings between them I saw the hull of another sailing ship, tied close. There was no room to pass between the planks of the ship and the piles. Trapped so soon?!

"This is your day for panic," I whispered aloud, the sound of my voice covered by the slapping of the waves. "You can't go back, so carry on you must. The hull of this ship has to curve away. Just dive down and swim along it until you find another opening between the piles." Ho-ho. Sounded very easy to do. I kicked my boots off and breathed deep. But my trepidation grew with each shuddering breath that I drew in. When my head was swimming with oxygen intoxication I let out the last lungful and dived.

It was a long, dark and apparently endless swim. I ran my left hand along the ship's hull to guide me. Collecting some heroic splinters at the same time. On and on with no glimmer of light in front or above. This must be a very big ship. There was fire in my lungs and desperation in my swimming before I saw light ahead. I came up as quietly as I could by the ship's bow. Trying not to gasp as I exhaled and drew in life and fresh air.

Looking up at a sailor standing on the rail above, turning toward me.

I sank out of sight again, forcing myself deep under the water, swimming on with my lungs crying out for air, until I saw the black bulk of the next ship ahead of me, forcing myself to swim on to the last glimmer of light before floating up to the surface again.

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

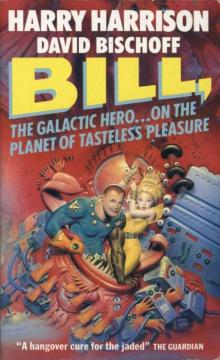

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures