- Home

- Harry Harrison

King and Emperor thatc-3 Page 3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Read online

Page 3

Halim did not rely on his ram alone. His master, bin-Tulun, was no Arab by blood, but a Turk from the central steppe lands of Asia. He had supplied a dozen of his countrymen to each ship. As they lined the sides they began to string their bows: the composition bows of Central Asia, wood at the center, sinew on the outside, the side to which the bow bent before it was strung, hard horn on the inside, all glued and assembled with fanatic care. Again and again Halim had seen the Rumi shot down before ever they came to a handstroke, their own weak wooden bows outranged by a hundred yards, not able to pierce even good stout leather.

As the light grew across the water Halim realized that the ships now closing on him at ramming speed like his own were not the kind he expected. Their prows were painted red, were higher out of the water than any he had seen before, and from the warships' hulls he could see sprouting not the crucifixes of the Rumi, but gilded pictures, icons.

Not the fleet of the Sicilians then, or their holy father in Rome, but the Red Fleet of the Byzantines, of which Halim had only heard. He felt something at his heart—not fear, for that was impossible to the true believer, nor even surprise, but intellectual worry: how could the Byzantine fleet be here, five hundred miles from its bases, more days than it could row without exhaustion? Concern, as well, that this news and what it meant should be passed to his master.

But passed it would be. Halim signaled to his steersman not to meet the charging enemy bow to bow, but to swerve aside, trusting to greater handiness, to shave away one row of oars as they passed, and pour in a deadly volley from his bowmen, each of them able to shoot a shaft a second and never miss. He ran forward himself along the starboard catwalk, drawing his saber, not with the intention of striking a blow but to encourage his men.

There would be a moment of danger here. For as he turned aside, the Greek, if he were fast enough, could accelerate and strike bow to flank, driving through below the waterline, and reversing oars instantly to shake the smaller craft off and leave her crew struggling in the water, her chained slaves drowning desperate and trapped.

Yet the slaves knew that too. As the ship swung barely fifty yards from the white water of her enemy's prow, the starboard side braked with their oars as one man, the port side slaves swung with all the strength in their bodies. Then a concerted momentary glance from both sides at each other to pick up the time, and the ship leapt forward as if it were the first stroke that any man had made that day. The bowmen bent their bows and picked their targets among the faces crowding the rail.

There was something there in the middle of the boat. Halim could not see clearly what it was, but he could see some metal contrivance, like a copper dome, lit brilliantly not only by the rising sun but by some flare or flame beneath it. Across the water, over the hiss of the oars and the blare of trumpets, came a roaring noise like that of some great beast, cut by a high and eldritch whistle. He could see two men pumping desperately at a handle, two more leveling a nozzle over the side.

Greek ships and the Greek fire. Halim had heard of this weapon, but never seen it. Few men who saw it lived to say how it should be countered. Yet he had heard one thing, which was that if its crew could be killed or distracted while they prepared its action, then it became as dangerous to its own side as to the enemy.

Halim began to shout orders to the Turks in his own craft, wishing vainly as he did so that he could shout the same warning to the hundred ships streaming in his wake, to attack, he could now see, no more than a score of the Byzantines.

As the breath filled his lungs, and the first arrows began to fly, the whistle in Halim's ears rose to a shriek, a barked command came from the vessel lunging towards him. Halim saw the nozzle swing to face him, caught a strange reek in the air, saw a glow at the mouth of the nozzle. Then the air was full of fire, searing out his eyeballs, crisping his skin so that pain struck him like a club from all directions at once. Halim breathed in death as he tried to scream, his lungs filling instantly with flame. As he fell back into the blaze that was his flagship he heard the simultaneous agony of a hundred slaves, and took it with the last flick of consciousness as the tribute for the entry of a warrior into Paradise.

The Tulunid scout boats, creeping cautiously into the water where their fleet had been barely three days before, found nothing to explain its disappearance. Except charred timbers floating, the headless corpse of a circumcised believer who had survived the burning only to meet death for refusing baptism. And still chained to the timber he had pulled free from his sunken ship in a frenzy of fear, a slave half mad with thirst. The story he croaked out sent the scout boats racing without further delay for the Egyptian shore.

News of the disaster did not outsail the fleet that caused it. A bare fortnight later, Ma'mun bin-Khaldun, commander of the faithful on the new-conquered island of Mallorca, could only watch grimly from the shore as the Byzantine fleet brushed aside the attempts at interception by his own always-manned inshore squadron, and then cruised slowly along the ranks of his massed invasion fleet, moored a hundred feet offshore, pouring out their Iblis-flame. His army had debarked months before, to set about the conquest of the island, leaving their ships with no more than an anchor-watch and a guard against surprise by the natives. As the Greeks came into sight, his few boat-keepers had quickly abandoned their charges, pulling furiously for the shore in dinghies. He would lose few men, other than the ones he would execute for fleeing without orders. Nevertheless the ships were a major loss.

Yet Ma'mun felt no great concern. Behind him he had a large and fertile island, its native inhabitants by now thoroughly tamed. He had immense stores of grain, olives, wine and beef, and could if need be support himself and his army indefinitely on the products of Mallorca itself. He had something more important than that as well, the breath of life itself to any Arab: he had water. And while the Byzantines had fire at sea, they would soon need to come to land, for water. No fleet of galleys could last long without it. They must already be at the limit of their endurance, if they had made the long passage from their bases on the islands of the Greeks.

Though there was something wrong there, Ma'mun reflected silently. If the Byzantines had indeed made the long passage down the Mediterranean, they would not be at the limit of their endurance, they would have passed it days ago. Therefore, they had not. They had touched land somewhere much closer. On his information, that was impossible. Therefore, his information was wrong. That was the dangerous element in this situation, Ma'mun concluded. Where could the Greeks have watered? In Sicily? By his understanding, Sicily was closely invested by the forces of the Tulunids, the Caliph of Egypt. Ma'mun himself had nothing but contempt for Tulun and his followers, mere Turks, barbarians from nowhere, followers in any case—till they rebelled—of the treacherous successors of Abdullah. He himself was an Umayyad and a member of the tribe of Quraysh, related by blood to the Caliph of Cordova, both of them descendants of that Abd er-Rahman who had fled the massacre in Persia when Umayyad power was broken. Nevertheless, while the Egyptians had no more love for him than he for them, he was surprised that some information or other had not reached him if Sicily had been retaken: it was not like the pale followers of Yeshua whom they mistakenly called the Christ to act so swiftly.

He would have to gain further information. Yet whatever the true state of affairs, there could be no doubt that those boats out there in the calm bay of Palma would soon be trying to find some unguarded spring or other. No doubt they hoped that he, Ma'mun, would be unable to guard every foot of shore on this rugged island. Now it would be their turn to be mistaken.

As he turned dismissively from the last moments of the destruction of his fleet, he became aware of some disturbance on the outer fringes of his guard. A young man was struggling in the grip of two warriors, calling out angrily. Angrily, not fearfully. Ma'mun signed to his guard-captain to let the young man through. If he had a word to say, let him say it. If he wasted the time of the commander of the faithful, he could go to the impaling-post as a warning to

others.

The young man fretfully pulling his clothes back into place had the face of a Qurayshi too, Ma'mun noticed. Most of his army now were the descendants of Berbers, converted Spaniards, even Goths. Ma'mun had been obliged to prohibit taunts of pork-eating, so sensitive were the sons of former Christians in his ranks. But this young man had no touch of the tow-brush about him, as lean and dark-faced as Ma'mun himself. He spoke, too, like a true Arab, without evasion or deference.

“Commander, the men on those ships are not Greeks, even if the ships throw out the Greek fire. Not all of them. Many are ferengis, Franks.”

Ma'mun raised an eyebrow. “How has it been permitted to you to see this? I have not seen it, and my eyes are keen enough to pick out the Rider of the Stars.” He meant the star in Orion's sword-belt which has, invisible to all but the keenest-sighted, a tiny companion sheltered by the light of its neighbor.

The young man smiled with irritating condescension. “I have that which enables me to see better even than that.”

The guard-captain standing at the young man's elbow stepped forward, aware that his master was on the edge of ordering the impaling-post to be set up. “The young man here, lord, is Mu'atiyah. A pupil of bin-Firnas.”

Ma'mun hesitated, pulling his beard. He himself had been named after the great Caliph of fifty years before, who had set up the great library and center of wisdom in Baghdad. He had the greatest respect for men of learning. And there was no doubt that Abu'l Qasim Abbas bin-Firnas was the glory of Cordova for his learning and his many experiments. With less impatience in his voice he said, “Show us then, the wisdom of your master.”

Smiling once more, the young Mu'atiyah pulled from his sleeve an object like a stout bottle covered in leather.

“Know,” he said, “that my master, being advanced in years, found a dimness coming upon his eyes, so that he could see only that which was further away than his own arm's reach. For many years he had studied the science of making glass, and the stones from which it might be made. So, by accident, one day he discovered that if one looked through stones of a certain kind and shape, that which was too close for his eyes became as it were far away, so that he might read it. And, not by accident but by design, he studied many hours till he could find a glass shape that would do likewise for him, and restore to him the liberty of his books.”

“But that is to make the close far away,” replied Ma'mun. “Here we have need of the opposite.”

Again the young man smiled, again provoking Ma'mun with his display of confidence. “That is what I, Mu'atiyah, have discovered. That if one takes not one but two glasses, and looks first through one and then through the other, the far away comes close.”

Thoughtfully, Ma'mun reached over and took the leather object from the young man's hand, disregarding a look of alarm and a sudden babble of explanation. He put it to his eye, looked a moment, lowered it.

“I see only the tiniest of images.”

“Not like that, lord, mighty one.” The young man was at least showing agitation for the first time. It was often so with the learned, Ma'mun conceded grimly. What upset them the most was not the threat of death but the fear that they would not be able to display their abilities. He allowed the young man to take the object from his hand, reverse it so that he looked through what appeared to be the neck.

“Yes, lord. On the deck of the lead ship I see a Greek, with a curled beard, standing by an image of the holy.” Ma'mun's face twisted in disgust, and he spat ritually to avert the contamination created by any image of the divine. “But by him there is a fair-haired Frank, all in metal armor. They are arguing, pointing in different directions.”

“What are they saying?”

“My art deals with sight, not sound.”

“Very well.” Ma'mun signed to the guard-captain. “Take the young man from his place in the ranks, keep him with yourself. If I have need of his art I will send for him. If I do not, the armies of Spain have more need of wise men than of brave ones. We must keep him safe. And, Mu'atiyah, if you tell me where the Greek amiral means to land for water before I can see myself, I will fill your mouth with gold. If you tell me wrong I will melt it first.”

He turned away, calling to his commanders of divisions. Behind him the young man raised his spyglass again, seemed to be attempting to gain a clearer view by moving his eye in and out from the eyepiece.

From time to time in his babbling flow of talk, the Mallorcan villager cast a fearful glance sideways. He had reason to feel fear. The villager had seen the fleet of great red galleys pull round the point, having burned to the waterline the ships that had brought the circumcised to Mallorca long months before. He had realized they must be searching for water, and theorized that whoever they were, the enemies of Muhammad must be his friends. So, when they came ashore and began to set up their camp, and after he had crept close enough to see the crucifixes and the saints' images raised, he had come shyly and slowly forward to volunteer his services: hoping for some reward that might keep him from starvation. Hoping too for revenge on the fierce dark-faced raiders who had stolen from him wife and son and daughters.

Yet he had not reckoned on facing quite such strange and menacing allies. The villager had no language in common with the Greek sailors, or with the German soldiers whom they transported. He had been passed on, though, from guard-post to guard-post till they found a Latin-speaking chaplain. If he spoke slowly and listened carefully, he and the Mallorcan could understand each other, for the Mallorcan's peculiar dialect was no more than the Vulgar Latin of old time, spoken badly and without a schoolmaster for generation after forgotten generation. So much the Mallorcan had expected. He had not expected to find anyone like the man who stood with a scowl on his face next to the Christian priest and his wizened informant.

Agilulf, Ritter of the Lanzenorden, once companion of the great Emperor Bruno himself, and now commander of the expedition against the Moors, stood a foot taller than either priest or villager. His height was increased by the visored iron helmet he wore, and the black plume in it that marked his rank. Yet what the villager could not understand, or hardly believe, was not the man but his dress. From head to foot Agilulf seemed to be made of iron. He wore helmet, mail shirt hanging to his knees, greaves on his calves and beneath them iron-plated boots. Iron studded his gauntlets and rimmed the long kite-shaped shield he carried: a horseman's shield, drawn out in a kite shape to protect the lancer's left leg when he charged, but carried by Agilulf on foot as if weight meant nothing to him. Nor heat. Beneath the iron he wore leather to prevent links being beaten into his flesh, beneath the leather he wore hemp to soak up the sweat. In the late afternoon heat of the Balearics in spring time, the sweat sprang out from under the hairline and dripped steadily down into his beard. He took no notice, as if to notice discomfort was beneath his dignity. To the villager, who had never seen more iron in his life than it would take to sheathe the spike on his primitive plow, the German seemed a creature from another world. The cross painted on his shield was little comfort.

“What does he say?” demanded Agilulf, tiring of listening to slow exchanges in a language he could not follow.

“He says there is a good spring half a mile away, where we could fill as many water-barrels as we wish. But he says the Moslems know of it and use it too. They will have seen us already. The main army of the invaders is a bare ten miles off. They move with the speed of the wind, he says. That is how he lost his family: taken before anyone in his village knew raiders had landed.”

Agilulf nodded. He showed none of the dismay that Pedro the villager had expected. “Does he know how many men the Moslems have?”

The priest shrugged. “He says ten thousand thousand. That could mean anything over a couple of hundred.”

Agilulf nodded again. “Very well. Give him some grain and a flask of wine, and let him go. I expect there are many like him skulking in these hills. Tell him when the Moslems have broken there will be a reward for heads. They can round up th

e stragglers for us.”

Agilulf turned away, shouting orders to his men to form up the watering-party. As usual, protest and expostulation from the Greek sailors, uneasy on land, convinced that at any moment a horde of ghazis would rush from the woods and overwhelm them. Agilulf paused for a moment to explain his plan to the Greek commander.

“Of course they'll rush us,” he said. “At dawn. My cross-bowmen and your rowers will hold them in front for a few minutes. Then I and my knights and companions will take them from behind. I wish we had horses to make our charge swifter. But it will come to the same thing in the end.”

The Greek looked after the iron man as he stalked on his way. The Franks, he thought. Clumsy, illiterate, heretical peasants. Why are they so confident so suddenly? They have swept out of the West like the followers of Muhammad from the East two hundred years ago. I wonder if we will find them any better than the wine-haters?

Ma'mun made no effort to conceal his dawn attack, once his men were in place. He had counted the ships of the enemy: a bare score. No matter how crowded with men they were, they could not hold more than two thousand at the very most. He had ten thousand. Now was the time to avenge the destruction of his ships. The Greek fire, he knew, could not be transported overland. He feared nothing else. He allowed his priests to call out the dawn salat, regardless of the warning it gave, and led his men in their ceremonial prayers. Then he drew his saber, and signaled to his commanders-of-a-thousand to lead the assault.

In full daylight the army of the faithful ran forward in the tactic that had led them to victory over army after army of Christians: in Spain, in France, in Sicily, at the gates of Rome itself. A loose wave of men with spears and swords, without the locked shields and heavy body-armor of the West, but driven on by contempt for death, assurance that those who died fighting the unbelievers would live for ever amid the houris of Paradise.

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

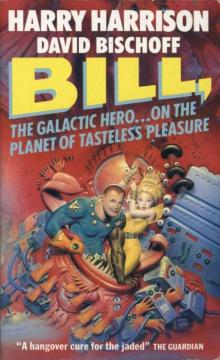

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures