- Home

- Harry Harrison

The Technicolor Time Machine Page 3

The Technicolor Time Machine Read online

Page 3

“All right, all right. Lectures I don’t need. Make him comfortable and oil him up with a few drinks and let’s get rolling.”

Tex pushed a chair against the back of the Viking’s legs and he sat down, glaring. Barney took a bottle of Jack Daniels from the bar concealed by the fake Rembrandt and poured a highball glass half full. But when he held it out to the Viking the man jerked his head away and rattled the chains that bound his wrists.

“Eitr!” [4] he snarled.

“He thinks that you are trying to poison him,” Lyn said.

“That’s easy to take care of,” Barney said, and raised the glass and took a long drink. This time the Viking allowed the glass to be put to his lips and began to drink, his eyes opening wider and wider as he drained it to the last drop.

“Ooinn ok Frigg!” [5] he bellowed happily and shook the tears from his eyes.

“He should like it, at $7.25 a bottle, plus tax,” L.M. said. “You can bet they don’t have that kind of stuff where he comes from. Nor Lifebuoy neither. Ask him again about the name.”

The Viking frowned with concentration while he listened to the question repeated in a variety of ways, and answered readily enough once he understood.

“Ottar,” he said and looked at the bottle longingly.

“Now we’re getting someplace,” L.M. said and looked at the clock on his desk. “We’re also getting onto four o’clock in the morning and I want to get things settled. Ask this Ottar about the rate of exchange—what kind of money do they have, Lyn?”

“Well—they barter mostly, but mention is made of the-silver mark.”

“That’s what we want to know. How many marks to the dollar, and tell him not to give any fancy bank figures. I want the free market price, we’ve been had this way before, and I’ll buy the marks in Tangier if I have to—”

Ottar bellowed and hurled himself out of the chair knocking Barney into a row of potted plants, which collapsed under him, and grabbed up the bourbon bottle. He had it raised to his mouth when Tex hit him with the sap and he slumped unconscious to the floor.

“What’s this?” L.M. shouted. “Murder in my own office? Crazy men I got enough of in the organization, so take this one back where he came from and find one thai speaks English. I don’t want any translators next time.”

“But none of them speak English,” Barney said crossly, pulling fragments of cactus from his sleeve.

“Then teach one—but no more crazy men.”

4

Barney Hendrickson suppressed a groan, and the hand that raised the carton of black coffee to his lips tremored ever so slightly. He had forgotten how many hours—or centuries—it had been since he had had any sleep. One difficulty had followed another through the night, until the dawn of a new day brought its own problems. Dallas Levy’s voice buzzed in the earpiece of the phone like an irritated wasp while Barney sipped his coffee.

“I agree, I agree, Dallas,” he rasped in answer, his vocal cords eroded by three chain-smoked packs of cigarettes. “Just stick by him and keep him quiet, no one ever goes near those old storerooms… Well you’ve been on double time the last three hours… All right then, treble time now, I’ll okay the vouchers. Just keep him locked up and quiet until we decide what to do with him. And tell Dr Lyn to get up here as soon as he has finished talking to B.O. Plenty.”

Barney hung up the phone and tried to concentrate on the budget sheet before him. So far most of the entries were followed by penciled question marks; this was going to be a hard picture to cost. And what would happen if the police got wind of the Viking locked up down below? Could he be charged with kidnapping someone who had been dead almost a thousand years? “The mind reels,” he mumbled, and reached for the coffee again. Professor Hewett, still apparently as fresh as ever, paced back and forth the length of the office, spinning a pocket calculator and scribbling the results in a small notebook.

“Any results yet, Prof?” Barney asked. “Can we send anything bigger than that truck back in time?”

“Patience, you must learn patience. Nature yields up her secrets only with the greatest reluctance, and a misplaced decimal point can make disclosure impossible. There are many factors that enter the equations other than the accepted four dimensions of physical measurement in time. We must consider three additional dimensions, those of displacement in space, mass, a cumulative error, which I am of the opinion is caused by entropy—”

“Spare me the details, just the answer, that’s all I want,” His intercom buzzed and he told his secretary to show Dr. Lyn in. Lyn refused a cigarette and folded his long form into a chair.

“Out with the bad news,” Barney said. “Unless that is your normal expression. No luck with the Viking?”

“As you say, no luck. There is a communication problem, you realize, since my command of Old Norse is far from perfect, which must be coupled with the fact that Ottar has little or no interest in what I am trying to discuss with him. However, I do feel that with the proper encouragement he could be convinced that he should learn English.”

“Encouragement… ?”

“Money, or the eleventh-century equivalent. Like most Vikings he is very mercenary and will do almost anything to gain status and wealth, though of course he prefers to get it by battle and killing.”

“Of course. We can pay him for taking his language lessons, bookkeeping has worked out a rate of exchange and it’s all in our favor, but what about the time factor? Can you have him speaking English in two weeks?”

“Impossible! With a cooperative student this might be done, but not with Ottar. He is reluctant at best, in addition to the not considerable factor that he refuses to do anything until he is released.”

“Not considerable!” Barney said, and had the sudden desire to tug at a fistful of his own hair. “I can just see the hairy nut with his meat ax on the comer of Hollywood and Vine. That’s out!”

“If I might offer a suggestion,” Professor Hewett said stopping his pacing in front of Barney’s desk. “If Dr. Lyn were to return with this aborigine to his own time there would be ample opportunity to teach him English in his own environment, which would both reassure and calm him.”

“It would not reassure or calm me, Professor,” Lyn said coldly. “Life in that particular era tends to be both brutish and short.”

“I’m sure precautionary measures can be taken, Doctor,” said Hewett, giving his calculator a quick spin. “I would think that the philological opportunities would far outweight the personal factor…”

“There is of course that,” Lyn agreed, his unfocused eyes staring at nouns, roots, cases and genders long buried by time.

“Plus the important point that in this manner the time factor can be altered to suit our needs. Gentlemen, we can collapse or stretch time as we will! Dr. Lyn can have ten days, or ten months, or ten years, to teach the language to Ottar, and between the moment when we leave him in the Viking era and the moment when we see him again but a few minutes need have passed from our point of view.”

“Two months will be adequate,” Lyn snapped, “if you wish to take into consideration my point of view.”

“It’s agreed then,” Barney said. “Lyn will go back with the Viking and teach him English, and we’ll arrive with the company two months later Viking-time to start the production rolling.”

“I have not agreed,” Lyn persisted. “There are dangers…”

“I wonder what it would feel like to be the world’s single greatest authority on Old Norse?” Barney asked, having had some experience with the academic mind, and the wide-eyed expression on Lyn’s face revealed that his shaft had sunk home. “Right. We’ll work out the details later. Why don’t you go see if you can explain this to Ottar. Mention money. We’ll get him to sign a completion and penalties contract, so you’ll be safe enough as long as he wants his pay.”

“It might be possible,” Lyn agreed, and Barney knew that he was hooked.

“Right then. You get down to Ottar and put the deal

to him, and while you’re getting his okay I’ll have the contract department draw up one of their barely legal, lifetime-at-hard-labor contracts.” He flipped on the intercom. “Put me through to contracts, will you, Betty. Has the Benzedrine arrived yet?”

“I called the dispensary an hour ago,” the intercom squeaked.

“Well call them again if you expect me to live past noon.”

As Jens Lyn went out, a slight Oriental wearing pink slacks, a cerise shirt, a Harris Tweed sports jacket and a sour expression entered.

“Well, Charley Chang,” Barney boomed, sticking out his hand, “long time no see.”

“It’s been too long, Barney,” Charley said, grinning widely and shaking the outstretched hand, “Good to work with you again.”

They disliked each other intensely and as soon as their hands separated Barney lit a cigarette, and the smile vanished into the unhappy folds of Chang’s normal expression. “What’s cooking, Barney?” he asked.

“A wide-screen, three-hour, big-budget film—and you’re the only man who can write it.”

“We’re running out of books, Barney, but I’ve always thought that there was a good one in the Song of Solomon, sexy without being dirty—”

“The subject has already been chosen, a wholly new concept of the Viking discoveries of North America.”

Chang’s frown deepened. “Sounds good, Barney, but you know I’m a specialist. I don’t think this is up my alley.”

“You’re a good writer, Charley, which means everything is up your alley. Besides, ha-ha, let’s not forget your contract,” he added, slipping the dagger a few inches out of the scabbard so it could be seen.

“No, we can’t forget the contract, ha-ha,” Charley said coldly. “I’ve always been interested in doing a historical.”

“That’s great,” Barney said, pulling the budget sheet toward him again. The door opened and a messenger pushed in a trolley loaded with books. Barney pointed at them. “Here’s the scoop from the library, everything you need to know. Just take a quick flip through them and I’ll be with you in a minute.”

“A minute, sure, sure,” Charlie said, looking coldly at the twenty-odd thick volumes.

“Five thousand seven hundred and seventy-three point two eight cubic meters with a loading of twelve thousand seven hundred and seventy-seven point six two kilograms at a power increase of twenty-seven point two per cent,” Professor Hewett suddenly said.

“What the hell are you talking about?” Barney snapped.

“Those are the figures you asked for, the size of load the vremeatron will be able to handle with an increased power supply.”

“Very nice. Now will you translate it into American.”

“Roughly speaking”—Hewett rolled his eyes up and mumbled quickly under his breath—“I would say that a fourteen-ton load could be temporally moved, measuring twelve feet by twelve feet by forty feet.”

“That’s more like it. That should hold anything we might possibly need.”

“Contract,” Betty said, dropping an eight-page multifolded document onto his desk.

“All right,” Barney said, slipping quickly through the crisp sheets. “Get Dallas Levy up here.”

“Miss Tove is waiting outside to see you.”

“Not now! Tell her my leprosy is acting up. And where are those bennies? I’m not going to get through this morning on coffee alone.”

“I’ve rung the dispensary three more times, there seems to be something about a staff shortage today.”

“Those unfeeling bastards. You better get down there and bring them back yourself.”

“Why Barney Hendrickson—it must have been years…”

The hoarse-voiced words hurtled across the office and left silence in their wake. Gossipmongers said that Slithey Tove had the acting ability of a marionette with loose strings, the brain of a chihuahua and the moral standards of Fanny Hill. They were right. Yet these qualities, or lack of qualities, did not explain the success of her pictures. The one quality that Slithey did have, in overabundance, was femaleness, plus the ability to communicate on what must have been a hormone level. She did not generate an aura of sex, but rather one of sexual availability. Which was true enough. This aura was strong enough to carry, scarcely diminished, through all the barriers of film, lenses and projectors to radiate, hot and steaming, from the silver screen. Her pictures made money. Most women didn’t like them. Her aura, now operating unhampered by time, space or celluloid, swept the room like a sensual sonar, clicking with passion unrestrained.

Betty sniffed loudly and swept out of the room, though she had to slow momentarily to get past the actress, who stood sideways in the doorway. It was said, truthfully, that Slithey had the largest bust in Hollywood.

“Slithey…” Barney said, and his voice cracked. Too many cigarettes, of course.

“Barney darling…” she said, as the smoothly hydraulic pistons of her rounded legs propelled her slowly across the office, “it’s been ages since I’ve seen you.”

With her hands on the desk top, she leaned forward and gravity tugged down at the thin fabric of her blouse and at least 98 per cent of her bosom swam into view. Barney felt he was flying upside down into a fleshy Grand Canyon.

“Slithey,” Barney said, springing suddenly to his feet: he had almost fallen into this trap before. “I want to talk to you about this picture we’re planning, but you see I’m busy just now…”

Inadvertently he had taken her arm—which throbbed like a great, hot, beating heart under his fingers as she leaned close. He snatched his hand away.

“If you’ll just hold on a bit, I’ll be with you as soon as I can.”

“I’ll just sit over there against the wall,” the husky-voice said. “I know I won’t be in the way.”

“You want me?” Dallas Levy asked from the open doorway, talking to Barney while his eyes made a careful survey of the actress. Hormone contacted hormone and she inhaled automatically. He slowly smiled.

“Yes,” Barney said, digging the contract out of the litter of papers on his desk. “Take this down to Lyn and tell him to get his friend to sign it. Any trouble?”

“Not since we found out he likes burnt beefsteak and beer. Anytime he starts acting up we slip him another steak and a quart of beer and he forgets his troubles. Eight steaks and eight quarts so far.”

“Get that signature,” Barney said, and his gaze fell accidentally on Slithey, who had oozed into the armchair and crossed her silk-shod legs. Her garters had little pink bows on them…

“What do you say, Charley?” Barney asked, collapsing into his swivel chair and spinning it about. “Any ideas yet?”

Charley Chang raised the thick volume he held in both hands. “I’m on page thirteen of this one and there are a few more books to go.”

“Background material,” Barney told him. “We can-rough out the main story lines now and you can fill in the details later. L.M. suggested a saga, and we can’t go wrong with that. We open in the Orkney Islands around the year 1000 when there is plenty of trouble. You have Norse settlers and Viking raiders and things are really hotting up. Maybe you open with a Viking raid, the dragon ship gliding across the dark waters, you know.”

“Like opening a Western with the bankrobbers silently riding into town?”

“That’s the idea. The hero is the chief Viking, or maybe the head man ashore, you’ll work that out. So there’s some fighting, then some more of the same, so the hero decides to move his bunch to the new world, Vinland, which he has just heard about.”

“Like the winning of the West?”

“Right. Then the voyage, the storm, the shipwreck, the landing, the first settlement, the battle with the Indians. Think big because we’re going to have plenty of extras. End on a high note, looking into the sunset.”

Charley Chang scribbled notes on the flyleaf of the book as Barney talked, nodding his head in agreement. “Just one thing more,” he said, holding up the book. “Some of the names of the gu

ys in this book are really a gas. Listen to this, here’s one called Eyjolf the Foul, who has a friend name of Hergil Hnappraz. And Polarbear Pig, Ragnar Hairybreeks—a million more. We could play this for laughs… ?”

“This is a serious film, Charley, just as serious as any you have ever done from—”

“You’re the boss, Barney. Just a suggestion. But what about the love interest?”

“Work her in early, you know how to do it.”

“That role is made for me, Barney darling,” the voice whispered in his ear as warm arms wrapped him and he began to drown in a sea of resilient flesh.

“Don’t let him sweet-talk you, Slithey,” he heard a muffled voice say. “Barney Hendrickson is my buddy, indeed my old buddy, but a mighty good businessman to boot, shrewd, so no matter what you promise him, I’m sorry to have to say this, I gotta look closely at all contracts before we sign.”

“Ivan,” Barney said, struggling free of the perfumed octopoid embrace, “just take your client aside for a moment then I’ll be with you. I don’t know if we can do business, but at least we can talk.”

Ivan Grissini, who, despite the fact that his lank hair, hawk nose and rumpled, dandruff-speckled suit made him look like a crooked agent, was a crooked agent. He could smell a deal ten miles upwind in a hailstorm and always carried sixteen fountain pens that he filled ritually each morning before leaving for the office.

“Sit over here, baby,” he said, levering Slithey toward the comer with a long-practiced motion. Since she wasn’t stuffed with greenbacks he was immune to her charms. “Barney Hendrickson is a man good as his word, even better.”

The phone rang just as Jens Lyn came in waving the contract. “Ottar cannot sign this,” he said. “It is in English.”

“Well translate it, you’re the technical adviser. Hold on.” He picked up the phone.

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

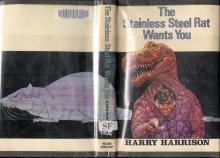

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

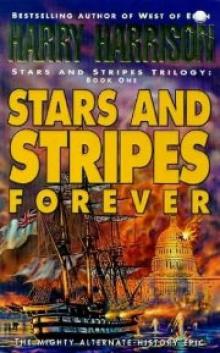

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

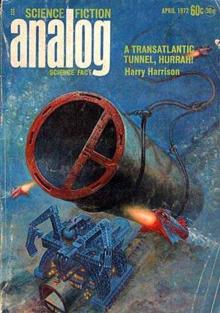

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

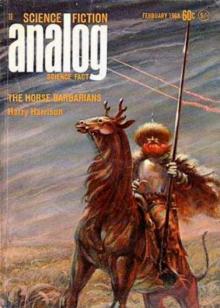

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

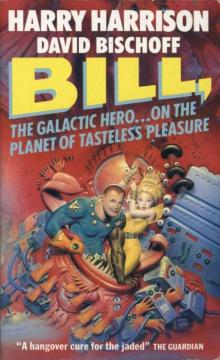

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures