- Home

- Harry Harrison

The Hammer & the Cross Page 3

The Hammer & the Cross Read online

Page 3

“It would be a sin against your soul to forgive these deeds. It would imperil the salvation of every man around this table. No, King, give him to us. Let us show you what we have made for you, for those who molest Mother Church. And when the news of that reaches back to the pagans, the robbers from the sea, let them know that Mother Church’s arm is as heavy as her mercy is long. Let us give him to the serpent-pit. Let us make men talk of the wormyard of King Ella.”

The king hesitated, fatally. Before he could speak, the sharp agreement of the other monks and of the archbishop was echoed by the rumble of surprise, curiosity, approval from his warriors.

“I have never seen a man given to the worms,” said Wulfgar, his face beaming with pleasure. “It is what every Viking in the world deserves. And so I shall say when I return to my own king, and I shall praise the wisdom and the cunning of King Ella.”

The black monk who had spoken rose to his feet: Erkenbert the dreaded archdeacon. “The worms are ready. Have the prisoner taken to them. And let all attend—councillors, warriors, servants—to see the wrake and the vengeance of King Ella and Mother Church.”

The council rose, Ella among them, his face still clouded by doubt, but swept along by the agreement of his men. The nobles began to jostle out, calling already for their servants, friends, wives, women to join them, to see the new thing. Shef, turning to follow his stepfather, looked back at the last moment to see the black monks still clustered in a little knot at the end of the table.

“Why did you say that?” muttered Archbishop Wulfhere to his archdeacon. “We could pay a toll to the Vikings and still save our immortal souls. Why did you force the king to send this Ragnar to the serpents?”

The monk reached in his pouch and, like Cuthred, threw an object on the table. Then another.

“What are those, my lord?”

“This is a coin. A gold coin. With the script of the abominable worshippers of Mohammed on it!”

“It was taken from the prisoner.”

“You mean—he is too evil to let live?”

“No, my lord. The other coin?”

“It is a penny. A penny from our own mint here in Eoforwich. It has my own name on it, see—Wulfhere. A silver penny.”

The archdeacon picked up both coins and stowed them back in his pouch. “A very bad penny, my lord. Little silver, much lead. All the Church can afford in these days. Our slaves run away, our churls cheat on their tithes. Even the nobles give as little as they dare. Meanwhile the heathens’ pouches drip with gold, stolen from believers.

“The Church is in danger, my lord. Not that she may be defeated and pillaged by the heathen, grievous though that is, for from that we may recover. It is that the heathens and the Christians may make common cause. For then they will find that they have no need of us. We must not let them deal.”

Nods of agreement, even from the archbishop.

“So. To the serpents.”

The serpent-pit was an old stone cistern from the time of the Rome-folk, with a light roof hastily erected over it to keep off the drizzle. The monks of St. Peter’s Minster in Eoforwich were tender of their pets, the shining worms. All last summer the word had gone out to their many tenants scattered across the Church lands of Northumbria: Find the adders, seek them out in their basking places on the high fells, bring them in. So much remission of rent, so much remission of tithes for a foot-long worm; more for a foot and a half; more, disproportionately more for the old, the grandfather worms. Not a week had passed without a squirming bag being delivered to the custos viperarum—the keeper of the snakes—its contents to be lovingly tended, fed on frogs and mice, and on each other to promote their growth: “Dragon does not become dragon till it has tasted worm,” the custos would say to his brothers. “Maybe the same is true of our adders.”

Now lay brothers racked torches round the walls of the stone court to augment the evening twilight, carried in sacks of warm sand and straw and spread it on the floor of the pit to make the serpents fiery and active. And now the custos too appeared, smiling with satisfaction, waving along a gang of novices, each the proud—if careful—bearer of a leather sack that hissed and bulged disconcertingly. The custos took each bag in turn, held it up to the crowd now pushing and jostling round the low walls of the cistern, undid the lashings, and slowly poured the struggling inhabitants down into the pit. He moved a few paces as he did each one, to distribute his serpents evenly. His task done, he stepped back to the edge of the lane kept open for the great ones by brawny companions—the king’s own hearth-troop.

They came at last: the king, his council, their body-servants, the prisoner pushed along in the middle of them. There was a saying among the warriors of the North: “A man should not limp while both his legs are the same length.” And Ragnar did not limp now. Yet he found it hard to hold himself straight. Cuthred’s ministrations had not been gentle.

The great ones fell back when they came to the edge of the pit, and let the prisoner see what he faced. He grinned through broken teeth, his hands tied behind him, a powerful guard holding each arm. He still wore the strange shaggy clothes of tarred goatskin which had brought him his name. Erkenbert the archdeacon pushed forward to face him.

“That is the worm-yard,” he said.

“Orm-garth,” corrected Ragnar.

The priest spoke again, in simple English, the trade-talk of the merchants. “Know this. You have a choice. If you become Christian, you live. As a slave. No orm-garth then for you. But you must become Christian.”

The Viking’s mouth twisted in contempt. He spoke in reply, still in the trade-tongue. “You priests. I know your talk. You say I live. How? As a slave, you say. What you not say, but I know, is how. No eyes, no tongue. Cut legs, cut hough-sinews, no walk.”

His voice rose to a chant. “I fought in the front for thirty winters, always I struck with the sword. Four hundred men I killed, a thousand women I ravished, many minsters I burned, many men’s bairns I sold. Many have wept for me, I never wept for them. Now I come to the orm-garth, like Gunnar the god-born. Do your worst, let the shining worm sting me to the heart. I shall not ask for mercy. Always I struck with the sword!”

“Get on with it,” snarled Ella from behind the Viking. The guards began to hustle him forward.

“Stop!” Erkenbert called. “First bind his legs.”

They tied the unresisting man roughly, pulled him to the edge, balanced him on the wall, then—he looking round at the pushing but silent crowd—shoved him over. He fell a few feet, landing with a thump on top of a pile of crawling snakes. Instantly they hissed, instantly they struck.

The man in the shaggy tunic and breeches laughed once from the ground.

“They cannot bite through,” called a voice in disappointment. “His clothes are too thick.”

“They may strike at his hands or face,” called the serpent-keeper, jealous for the honor of his pets.

One of the largest adders indeed lay a few inches from Ragnar’s face, the two staring almost eye-to-eye, the forked tongue of the one almost touching the chin of the other. A long moment of pause.

Then, suddenly, the man’s head moved, shooting sideways, teeth agape. A threshing of coils, a mouth spitting blood, the snake lay headless. Again the Viking laughed. Slowly he began to roll, humping his body despite the bound arms and legs, trying to fall on the snakes with the full weight of hip or shoulder.

“He’s killing them,” cried the custos in mortal pain.

Ella moved forward in sudden disgust, clicking his fingers. “You and you. You’ve stout boots on. Go in and lift him out.

“I’ll not forget this,” he added in an undertone to the disconcerted Erkenbert. “You’ve made a damned fool of all of us.

“Now, you men, free his arms, free his legs, cut his clothes off, bind him again. You and you, go fetch hot water. Serpents desire heat. If we warm his skin they will be drawn to it.

“One more thing. He will lie still this time, to thwart us. Bind one arm to hi

s body and tie the left wrist to a rope. Then we can make him move.”

They lowered the prisoner again, still grinning, still unspeaking. This time the king himself steered the lowering to the spot where the snakes lay thickest. In a few moments they began to crawl to the warm body steaming in the chill air, writhing over it. Cries of disgust came from the women and servants in the crowd as they imagined the scales of the fat adders brushing over bare skin.

Then the king jerked his rope, again and again. The arm moved, the adders hissed, the disturbed ones struck, felt flesh, struck again and again, filling the man’s body with their poison. Slowly, slowly, the awed watchers saw his face begin to change, to puff, to turn blue. As his eyes and tongue began to bulge, finally he called out once more.

“Gnythja mundu grisir ef galtar hag vissi,” he remarked.

“What did he say?” muttered the crowd. “What does that mean?”

I know no Norse, thought Shef from his vantage point. But I know that bodes no good.

“Gnythja mundu grisir ef galtar hag vissi.” The words still rang in the mind of the massive man, weeks later and hundreds of miles to the east, who was standing in the prow of the longship easing gently up toward the Sjaelland shore. It was sheer chance that he had ever come to hear them. Had Ragnar been talking to himself alone? he mused. Or had he known someone would hear, would understand and remember? It must have been very long odds against anyone in an English court knowing Norse, or anyway, enough Norse to understand what Ragnar had said. But dying men were supposed to have insight. Maybe they could tell the future. Maybe Ragnar had known, or had guessed, what his words would do.

But if those were the words of fate, which would always find someone to speak them, they had chosen a strange route to come to him! In the crowd pushing round the orm-garth there had been a woman, concubine to an English noble, a “lemman,” as the English called such girls. But before she had been bought for her master in the slave-mart of London, she had plied the same trade in the court of King Maelsechnaill in Ireland, where much Norse was spoken. She had heard, she had understood. She had had the wit not to tell her master—lemmans without wit did not live to see their beauty fade—but she had whispered it to her secret lover, a trader going south. He had passed it on to the other members of his caravan. And among them there had been another slave, a former fisherman on the run, one who had taken special interest in it because he had seen the actual capture of Ragnar on the shore. In London, thinking himself safe, the slave had made a story of it to earn himself mugs of ale and hunks of bacon in the waterfront booths where all men were welcome, English or Frankish, Frisian or Dane, as long as their silver was good. And so the tale had come in the end to Northern ears.

The slave had been a fool, a man of no honor. He had seen in the tale of the death of Ragnar only excitement, strangeness, humor.

The massive man in the longship—Brand—saw in it much more. That was why he brought the news.

The boat was gliding in now along a long fjord, reaching into the flat, rich countryside of Sjaelland, easternmost of the Danish islands. There was no wind; the sail was furled up against the yard, the thirty oarsmen rowing a steady, unhurried, practiced stroke, the ripples of their progress fanning out across the flat, pondlike sea to caress the shore. Cows moved gently in rich meadows, fields of thickly shooting grain stretched into the distance.

The air of peace was totally deceptive, Brand knew. He was at the still center of the greatest storm in the North, its peace guaranteed only by hundreds of miles of war-torn sea and burning coastline. As they rowed in he had been challenged three times by naval patrols—heavy coastal warships never designed for the open sea, filled with men. They had let him through with increasing amusement, always keen to see a man try his luck. Even now two ships twice the size of his were cruising behind him, just to make certain there was no escape. He knew, his men knew, that worse lay ahead.

Behind him the helmsman passed the steering-oar to a crewman and strolled forward to the prow. For a few moments he stood behind his skipper, his head barely reaching the huge man’s shoulder blade, and then spoke. He spoke softly, taking care not to be overheard even by the foremost rowers.

“You know I’m not one to question decisions,” he murmured. “But since we’re here, and we’ve all stuck our pizzles well and truly in the wasps’ nest, maybe you won’t mind me asking why?”

“Since you came so far without asking,” replied Brand in the same low tones, “I’ll give you three reasons and charge you for none of them.

“One: This is our chance to gain lasting glory. This will be a scene for sagamakers and for poets until the Last Day, when the gods fight the giants and the brood of Loki is loosed on the world.”

The helmsman grinned. “You have enough glory already, champion of the men of Halogaland. And some men say the ones we are going to meet are the brood of Loki. Especially one of them.”

“Two, then: That English slave, the runaway who told us the tale, the fisherman running from the Christ-monks—did you see his back? His masters deserve all the woe in the world, and I can send it to them.”

This time the helmsman laughed aloud, but gently. “Did you ever see anyone after Ragnar had finished talking to him? And those we are going to visit are worse. Especially one of them. Maybe he and the Christ-monks deserve each other. But what of all the others?”

“So, then, Steinulf, it comes to three.” Brand lifted gently the silver pendant which hung round his neck and lay on his chest, outside the tunic: a short-hafted, double-headed hammer. “I was asked to do this, as a service.”

“By whom?”

“Someone we both know. In the name of the one who will come from the North.”

“Ah. Well. That is good enough for both of us. Maybe for all of us. But I am going to do one thing before we get too close to the shore.”

Deliberately, making certain his skipper saw what he was doing, the helmsman took the pendant which hung round his own neck and tucked it inside his tunic, pulling the collar so that no trace of the chain showed.

Slowly, Brand turned to face his crew and followed suit. At a word, the steady beat of the oars in the calm water checked. The oarsmen shuffled chains and pendants out of sight. Then the beat of oars resumed.

At the jetty ahead men could now be seen sitting or strolling, never looking at the approaching warboat, giving a perfect impression of total indifference. Behind them a vast dragon-hall lay like an upturned keel; behind it and round it, a vast confusion of sheds, bunkhouses, rollers, boatyards on the edge of the fjord, smithies, stores, rope-walks, corrals, barracoons. This was the heart of a naval empire, the power center of men intent on challenging kingdoms, the home of the homeless warriors.

The man sitting on the very end of the jetty ahead of him stood up, yawned, stretched elaborately and looked in the other direction. Danger. Brand turned to shout orders. Two of his men standing by the halliards ran a shield up to the masthead, its new-painted white face a sign of peace. Two others ran forward and eased the gaping dragon-head off its pegs on the prow, turning it carefully away from the shore and wrapping it in a cloth.

More men onshore suddenly became visible, now prepared to look directly at the boat. They gave no sign of welcome, but Brand knew that if he had not observed proper ceremonial his welcome would have been very different. At the thought of what might have happened—might still happen—he felt his belly give an unaccustomed twinge, as if his manhood was trying to crawl back within him. He turned his face out to the far shore, to ensure no expression betrayed him. He had been taught since he could crawl, Never show fear. Never show pain. He valued this more than life itself.

He knew also that in the gamble he was about to take, nothing could be less safe than a show of insecurity. He meant to bait his deadly hosts, draw them into his story: appear as a challenger, not a suppliant.

He meant to offer them a dare so shocking and so public that they would have no choice but to take it. It was not a plan

that allowed half measures.

As the boat nosed into the jetty ropes were thrown, caught, snubbed round bollards, still with the same elaborate air of carelessness. A man was looking down into the boat. If this had been a trading port he might have asked the sailors what cargo, what name, where from? Here the man raised one eyebrow.

“Brand. From England.”

“There are many men called Brand.”

At a sign two of the ship’s crewmen swung a gangplank from ship to jetty. Brand strolled across it, thumbs in belt, and stood facing the dockmaster. On the level boards he was looking down. Far down. He noted with inner pleasure the slight shift of the eyes as the dockmaster, no stripling himself, weighed up Brand’s bulk, realized that man-to-man, at least, he was outmatched.

“Some men call me Viga-Brand. I come from Halogaland, in Norway, where men grow bigger than Danes.”

“Killer-Brand. I have heard of you. But there are many killers here. It needs more than a name to be welcome.”

“I have news. News for the kinsmen.”

“It had better be news worth hearing if you disturb the kinsmen, coming here without leave or passport.”

“News worth hearing it is.” Brand looked directly into the dockmaster’s eyes. “Come to hear it yourself. Tell your men to come and hear it. Anyone who cannot be bothered to hear what I have to say will curse his laziness till the last day he lives. But of course if you all have an urgent appointment in the privy let me not ask you to keep your breeches up.”

Brand brushed past the other and strode wordlessly toward the plume of smoke rising from the great longhouse, the hall of the noble kinsmen, the place no enemy had seen and left alive and free to tell the tale—the Braethraborg itself. His men trooped off the ship and silently began to follow him.

The dockmaster’s lips twitched, finally, with amusement. He made a sign and his men, picking their spears and bows from concealment, began to straggle inland. A flag dipped in acknowledgement from the still-vigilant outposts on the headland two miles off.

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

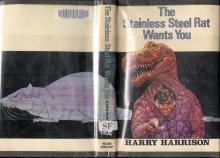

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

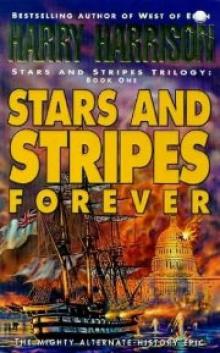

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

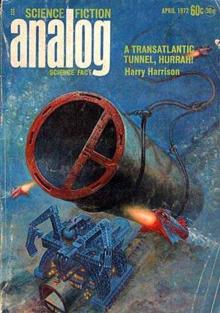

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

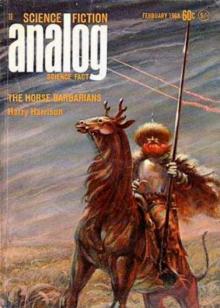

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

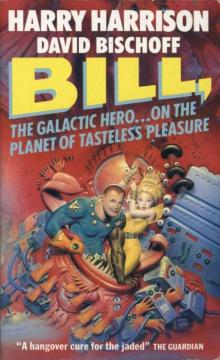

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures