- Home

- Harry Harrison

West of Eden Page 3

West of Eden Read online

Page 3

Behind them the coast of Maninlè was slipping out of sight. There was land barely visible on the horizon ahead, a chain of low islands stretching northwards. Satisfied, she bent over and spoke, expressing herself in the most formal way. When issuing orders she would be more direct, almost brusque. But not now. She was polite and impersonal, the accepted form of address to be used by one of lower rank to one of higher. Yet she was in command of this living vessel—so the one she spoke to must indeed be of exalted position.

“For your pleasure, there are things to be seen, Vaintè.”

Having spoken she moved to the rear, leaving the vantage point in the front clear. Vaintè clambered carefully up the ribbed interior of the fin and emerged onto the inner ledge, followed closely by two others. They stood respectfully to one side as she stepped forward. Vaintè held to the edge, opening and closing her nostrils as she smelled the sharp salt air. Erafnaiś looked at her with admiration, for she was indeed beautiful. Even if one did not know that she had been placed in charge of the new city, her status would have been clear in every motion of her body. Though unaware of the admiring gaze Vaintè still stood proudly, head high and jaw jutted forward, her pupils closed to narrow vertical slits in the full glare of the sun. Strong hands gripped hard while wide-spread feet balanced her; a slow ripple moved the bright orange of her handsome crest. Born to rule, it could be read in the very attitude of her body.

“Tell me what that is ahead,” Vaintè said abruptly.

“A chain of islands, Highest. Their name is their being. Alakas-aksehent, the succession of golden, tumbled stones. Their sands and the water about them are warm all the year round. The islands extend in a line until they reach the mainland. It is there, on the shore, that the new city is growing.”

“Alpèasak. The beautiful beaches,” Vaintè said, speaking to herself so that the others could not see or hear her words. “Is this my destiny?” She turned to face the commander. “When will we be there?”

“This afternoon, Highest. Certainly before dark. There is a warm current in the ocean here that carries us swiftly in that direction. The squid are plentiful so the enteesenat and the uruketo feed well. Too well sometimes. Those are some of the problems of commanding on a long voyage. We must watch them carefully or they go slowly and our arrival . . .”

“Silence. I wish to be alone with my efenselè.”

“A pleasure to me.” Erafnaiś spoke the words, backing away at the same time, vanishing below the instant she had finished.

Vaintè turned to the silent watchers with warmth in her every movement. “We are here. The struggle to reach this new world, Gendasi, is at an end. Now the greater struggle to build the new city shall begin.”

“We help, do as you bid,” Etdeerg said. Strong and solid as a rock, ready with all her strength to aid. “Command us—even unto death.” In another this might have sounded pretentious; not with Etdeerg. There was sincerity in every firm motion of her body.

“I will not ask that,” Vaintè said. “But I will ask you to serve at my side, my first aide in everything.”

“It will be my honor.”

Then Vaintè turned to Ikemend who drew herself up, ready for orders. “Yours is the most responsible position of all. Our future is between your thumbs. You will take charge of the hanalè and the males.”

Ikemend signed ready acceptance, pleasure—and firmness of endeavor. Vaintè felt the warmth of their companionship and support, then her mood changed to one of grimness. “I thank you both,” she said. “Now leave me. I will have Enge here. Alone.”

Vaintè held tight to the leathery flesh as the uruketo rode up and over a large wave. Green water surged across its back and broke against the black tower of the fin. Salt spray flew, some splashing Vaintè’s face. Transparent nictitating membranes slipped across her eyes, then slowly withdrew. She was not aware of the sting of the salt water for her thoughts were far ahead of this great beast that carried them across the sea from Inegban*. Ahead lay Alpèasak, the golden beaches of her future—or the black rocks that she would crash upon. It would be one or the other, nothing in between. In her ambition she had climbed high after leaving the oceans of her youth, leaving behind many in her efenburu, surpassing and climbing beyond efenburu many years her senior. If one wished to reach the peak one had to climb the mountain. And make enemies along the way. But Vaintè knew, as few others did, that making allies was equally important. She made it a point to remember all of the others in her efenburu, even those of lowly station, saw them when she could. Of equal, or greater importance, she had the ability to inspire respect, even admiration, among those of the younger efenburu. They were her eyes and her ears in the city, her secret strength. Without their aid she would never have been able to embark upon this voyage, her greatest gamble. Her future—or her failure. The directorship of Alpèasak, the new city, was a great step, an appointment that moved her past many others. The danger was that she might fail, for this city, the furthest ever from Entoban*, already had troubles. If there were delays in establishing the new city she was the one who would be brought low, so low she would never rise again. Like Deeste whom she was coming out to remove as Eistaa of the new city. Deeste had made mistakes, the work was going too slowly under her leadership. Vaintè was replacing her—and taking on all of the unsolved problems. If she failed—she too would b e repl aced in turn. It was a danger, but also a risk worth taking. For if it were the success they all hoped it would be, why then her star would be in the ascendancy and none could stop her.

Someone clambered up from below and stood beside her. A familiar presence yet a bittersweet one. Vaintè felt now the comradeship of one of her own efenburu, the greatest bond that existed. Yet it was tempered by the dark future that lay ahead. Vaintè had to make her efenselè understand what would happen to her once they were ashore. Now. For this would be the last chance that they would have to talk in private before they landed. There were too many listening ears and watching eyes below to permit her to speak her mind before this. But she would speak now, end this foolishness once and for all.

“We have made our landfall. That is Gendasi ahead. The commander has promised me that we will be in Alpèasak this afternoon.” Vaintè was watching out of the corner of her eye but Enge did not speak, merely signaled agreement with a motion of one thumb. The gesture was not insulting—nor was it revealing of any emotion. This was not going well, but Vaintè would not permit it to anger her or stop her from doing what must be done. She turned about and stood face to face with her efenselè.

“To leave father’s love and enter the embrace of the sea is the first pain of life,” Vaintè said.

“The first joy is the comrades who join you there,” Enge added, finishing the familiar phrase. “I abase myself, Vaintè, because you remind me of how my selfishness has hurt you . . .”

“I want no abasement or apologies—or even explanations of your extraordinary behavior. I find it inexplicable that you and your followers are not decently dead. I shall not discuss that. And I am not thinking of myself. You, just you, that is my concern. Nor do I concern myself with those misled creatures below. If they are intelligent enough to sacrifice their freedom for indecent philosophies, why then they are bright enough to make good workers. The city can use them. It can use you too—but not as a prisoner.”

“I did not ask to be unshackled.”

“You did not have to. I ordered that. I was shamed to be in the presence of one of my efenburu who was chained like a common criminal.”

“It was never my desire to shame you or our efenburu.” Enge was no longer apologetic. “I acted according to my beliefs. Beliefs so strong that they have changed my life completely—as they could change yours, efenselè. But it is pleasing to hear that you feel shame, for shame is part of self-awareness which is the essence of belief.”

“Stop. I feel shame only for our efenburu that you have demeaned. Myself, I feel only anger, nothing more. We are alone now, none can hear what I say. I a

m undone if you speak of it, but I know you won’t cause me injury. Hear me. Rejoin the others. You will be bound with them when you are brought ashore. But not for long. As soon as this vessel leaves I’ll have you away from them, free, working with me. This Alpèasak will be my destiny and I need your help. Extend it. You know what terrible things are happening, the cold winds blow more strongly from the north. Two cities are dead—and there is no doubt that Inegban* will be next. It is the foresight of our city’s leaders that before that happens a new and greater city will be grown on this distant shore. When Inegban* dies Alpèasak will be waiting. I have fought hard for the privilege of being Eistaa of the new city. I will shape its growth and ready it for the day when our people come. I will need help to do that. Friends around me who will work hard and rise with me. I ask you to join with me, Enge, aid me in this great work. You are my efenselè. We entered the sea together, grew together, emerged together as comrades in the same efenburu. This is a bond that is not easily broken. Join with me, rise with me, stay at my right hand. You cannot refuse. Do you agree?”

Enge had her head lowered, her wrists crossed to show that she was bound, lifting her joined hands before her face before she raised her eyes.

“I cannot. I am bound to my companions, the Daughters of Life, with a bond even stronger than that of my efenburu. They follow where I have led . . .”

“You have led them into wilderness and exile—and certain death.”

“I hope not. I have only spoke what is right. I have spoken of the truth revealed by Ugunenapsa, that gave her eternal life. To her, to me, to us all. It is you and the other Yilanè who are too blind to see. Only one thing can restore sight to you and to them. Awareness of the knowledge of death that will give you the knowledge of life.”

Vaintè was beside herself with anger, unable for the moment to speak, raising her hands to Enge like an infant so she could see the inflamed red of her palms, pushing them before her face in the most insulting of gestures. Growing more angry still when Enge was unmoved, ignoring her rage and speaking to her with tenderness.

“It need not be, Vaintè. You can join us, discover that which is larger than personal desires, greater than allegiance to efenburu . . .”

“Greater than allegiance to your city?”

“Perhaps—because it transcends everything.”

“There is no word for that which you are speaking. It is a betrayal of everything we live by and I feel only a great repulsion. Yilanè live as Yilanè, since the egg of time. Then into this order, like a parasite boring into living flesh, your despicable Farneksei appeared preaching this rebellious nonsense. Great patience was shown to her, yet she persisted and was warned, and persisted still—until there was no recourse but to expel her from her city. And she did not die, the first of the living-dead. Were it not for Olpèsaag the salvationer, she might be living and preaching dissension still.”

“Ugunenapsa was her name because through her this great truth was revealed. Olpèsaag was the destroyer who destroyed her flesh but not her revelation.”

“A name is what you are given, and she was Farneksei, inquirer-past-prudence, and she died for that crime. That is where it will end, this childish belief of yours, dirty thoughts that belong down among the corals and the kelp.” She took a deep and shuddering breath, fighting hard to get her temper under control. “Don’t you understand what I am offering you? One last chance. Life instead of death. Join with me and you will climb high. If this unsavory belief is important to you keep it, but speak to me not of it, or to any other Yilanè, keep it beneath your cloak where none can see. You will do it.”

“I cannot. The truth is there and must be spoken aloud . . .”

Roaring with rage, Vaintè seized Enge by the neck, her thumbs twisting cruelly at her crest, pushing her down and grinding her face into the unyielding surface of the fin.

“There is the truth!” she shouted, pulling Enge’s face about so she would understand every word clearly. “The birdshit that I grind your stupid moon-face into, that is reality and the truth. Out there is the truth of the new city at the edge of the wild jungle, hard work and filth and none of the comforts you have known. That is your fate, and certain death, I promise you if you do not abandon your superior attitude, your mewling . . .”

Vaintè spun about when she heard the tiny choking sound, to see the commander climbing up to join them, now trying to draw back out of sight.

“Get up here,” Vaintè shouted, hurling Enge down onto the ledge. “What does this interference, this spying mean?”

“I did not mean . . . there was no intent, Highest, I will leave.” Erafnaiś spoke simply, without subtlety or embellishment, so great was her embarrassment.

“What brought you here then?”

“The beaches. I just wanted to point out the white beaches, the birth beaches. Just around the point of land you see ahead.”

Vaintè was happy for the excuse to turn away from this distasteful scene. Distasteful to her because she had lost her temper. Something she rarely did because she knew that it placed weapons in others’ hands. This commander now, she would bear tales, nothing good could come of it. It was Enge’s fault, ungrateful and stupid Enge. She would be her own destiny now, get exactly the fate she deserved. Vaintè clutched hard to the edge as her anger faded, her breathing slowed, looking at the green shore so close to hand. Aware of Enge climbing to her feet, eager as they all were to see the beach.

“We will get as close as we can,” Erafnaiś said, “close inshore.”

Our future, Vaintè thought, the first glorious topping of the males, the first eggs laid, the first births, the first efenburu growing in the sea. Her anger was gone now and she almost smiled at the thought of the fat and torpid males lolling stupidly in the sun, the young happily secure in their tail pouches. The first births, a memorable moment for this new city.

Under the guidance of the crew the uruketo was being urged even closer inshore, almost among the breaking waves. The shore moved by, the beaches came into view. The beautiful beaches.

Enge and the commander were struck dumb by what they saw. It was Vaintè who cried aloud, a sound of terrible tortured pain.

It was drawn from deep inside her by the sight of the torn and dismembered corpses that littered the smooth sand.

CHAPTER THREE

Vaintè’s cry of pain ended abruptly. When she spoke next all complexity was gone from her words, all subtlety and form. Just the bare bones of meaning were left, a graceless and harsh urgency.

“Commander. You will lead ten of your strongest crewmembers ashore at once. Armed with hèsotsan. You will have the uruketo stand by here.” She pulled herself up and over the edge of the fin then stopped, pointing to Enge. “You will come with me.”

Vaintè kicked her toeclaws into the uruketo’s hide, her fingers found creases in the skin as she climbed down to its back and dived into the transparent sea. Enge was just behind her.

They surged up out of the surf beside the slaughtered corpse of a male. Flies were thick about the gaping wounds, covering the flesh and congealed blood. Enge swayed at the sight, as though moved by an invisible wind, winding her thumbs and fingers together, all unknowing, in infantile patterns of pain.

Not so Vaintè. Rock-hard and firm she stood, expressionless, with only her eyes moving over the scene of slaughter before her.

“I want to find the creatures that did this,” she said, her words betraying no emotion, stepping forward and bending low over the body. “They killed but did not eat. They are clawed or tusked or horned—look at those slashes. Do you see? And not only the males, but their attendants are dead too, killed the same way. Where are the guards?” She turned about to face the commander who was just emerging from the sea with the armed crewmembers, waving them forwards.

“Spread out in a line, keep your weapons ready, sweep the beach. Find the guards who should have been here—and follow those tracks and see where they lead. Go.” She watched them move out, turning

about only when Enge called to her.

“Vaintè, I cannot understand what kind of creature made these wounds. They are all single cuts or punctures, as though the creature had only a single horn or claw.”

“Nenitesk have a single horn on the end of their noses, large and rough, while huruksast also have a single horn.”

“Gigantic, slow, stupid creatures, they could not have done this. You yourself warned me of the dangers of the jungles here. Unknown beasts, fast and deadly.”

“Where were the guards? They knew the dangers, why were they not doing their duty?”

“They were,” Erafnaiś said, walking slowly back down the beach. “All dead. Killed the same way.”

“Impossible! Their weapons?”

“Unused. Fully loaded. This creature, these creatures, so deadly . . .”

One of the crewmembers was calling out to them from far down the beach, her body movements unclear at this distance, the sound of her voice muffled. She ran towards them, clearly greatly agitated. She would stop, attempt to speak for an instant, then run closer until finally her meaning was finally understood.

“I have found a trail . . . come now . . . there is blood.”

There was uncontrolled terror in her voice that added grim weight to what she had said. Vaintè led the others as they moved quickly to join her.

“I followed the trail, Highest,” the crewmember said, pointing into the trees. “There was more than one of the creatures, five I think, a number of tracks. All of them end at the water’s edge. They are gone. But there is something else, something you must see!”

“What?”

“A killing place of much blood and bones. But something . . . else. You must see for yourself.

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

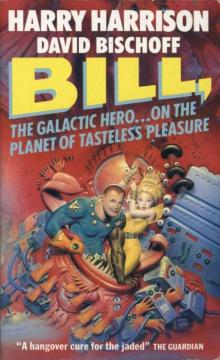

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures