- Home

- Harry Harrison

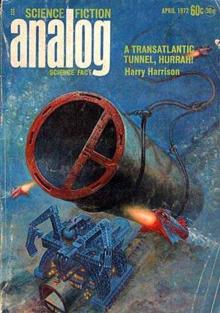

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Page 3

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Read online

Page 3

"I could not agree more warmly, sir! As you undoubtedly know I am a man of firm Tory persuasion and strongly back my party's position that dominion status be granted in the manner you say."

He rose and pounded the desk soundly as he said this, then extended his hand to the other, a social grace he had chosen to ignore when Washington had entered, undoubtedly because of the delicate nature of their familial relationship. Washington could do no less so stood and shook the hand firmly. They stood that way for a long moment then the marquis dropped his eyes and released Washington's hand, coughing into his fist to cover his embarrassment at this unexpected display of emotion. But it had cleared the air for what was to come.

"We are upon difficult times with the tunnel, Washington, difficult times," said Cornwallis and his expression became as difficult as the times he alluded to with his forehead furrowed as a plowed field, the corners of his mouth drooping so far that his ample jowls fell an inch. "This immense project has worn two faces since the very beginning and the private face is the one I allude to now. I am sure that you have some idea of the intricate financing of an enterprise this size but I do not think you are aware of how political in nature the major considerations are. In simple—this is a government project, a sort, of immense works program. You are shocked to hear this?"

"I must admit, sir, that I am, at the minimum, surprised."

"As well you might be. This country and its mighty Empire are built upon the sound notion that strong men lead while others follow, weak men and inept corporations go to the wall, while the government and the crown keeps its nose out of private affairs. Which is all well and good when the economic weather is fair and the sun of the healthy pound beams down upon us all. But there are clouds across the face of that sun now as I am sure you are well aware. While the frontiers were expanding England grew fat with the wealth of the East India Company, the Hudson's Bay Company, the Inca-Andean Company and all the others flowing our way. But I am afraid the last frontier has been pushed back to the final ocean and a certain placidity has settled upon the world and its economy. When businesses can no longer expand they tend to contract and this industrial contractionism is rather self-perpetuating. Something had to be done to stop it. More men on the dole every day, workhouses full, charities stretched to the limit. Something, I say, had to be done. Something was done."

"Certain private businessmen, certain great corporations, met in camera and—with considerable reluctance I can assure you—decided that the overall solution of the problem was beyond them. Learned specialists in the field of economics were drawn into the discussions and at their insistence the still highly secret meetings were enlarged to include a committee from the Parliament. It was then that the tunnel project was first voiced, a project large enough to affect and stimulate the entire economy of both Britain and the American colonies. Yet its very size was its only drawback; not enough private capital could be raised to finance it. It was then that the final, incredible step was taken. Crown financing would be needed." He lowered his voice unconsciously. "The Queen was consulted."

This was a revelation of a staggering nature, a secret of state so well kept that Washington, privy as he was to the innermost operations of The Transatlantic Tunnel Company, had not the slightest intimation of the truth until this moment. He was stunned at first, then narrowed his eyes in thought as he considered the ramifications. He was scarcely aware that the marquis rose and poured them each a sherry from the cut crystal decanter on the sideboard, though his fingers took it automatically and raised it to his lips.

He finally spoke. "Can you tell me what is the degree of involvement of the government?"

"In for a penny, in for a pound. Private investors have so far subscribed about twelve percent of the needed sum. Her Majesty's Government has agreed to take eighty percent—but no more."

"Then we are eight percent short of our goal?"

"Precisely." The marquis paced the length of the room and back, his hands clasped behind him and kneading one another. "I've had my doubts from the beginning, God knows we have all had our doubts. But it was Lord Keynes who had his way, Queen's adviser, author of I don't know how many books on economics, ninety years if he is a day and still spry enough to take on all comers. He had us all convinced, it sounded so good when he told us how well it would work. Money in circulation, capital on the move, healthy profits for investors, businesses expanding to meet the needs for building the tunnel, employment all around, pay packets going out to the small merchants, a healthy economy."

"All of those things could be true."

"Damme, all those things will be true—if the whole thing doesn't go bust first. And it will go bust and things will be back to where they were, if not worse, unless we can come up with the missing eight percent. And, you will pardon my frankness, my boy, but it is your bloody fellow colonials who are tugging back on the reins. You can help us there, possibly only you can help us there. Without overexaggerating I can say the fate of the tunnel depends upon you."

"I will do whatever is needed, sir," Washington said quietly and simply. "You may count upon me."

"I knew I could, or I would not have had you here. Forgive my bad manners, it's been a deucedly long day and more to come. We have an agreement with your Colonial Congress and the Governor General—yes they were consulted, too; your economy shares the same debilitations as ours—to match equally all monies raised by private investors in the Americas. There has been but a trickle where we needed a flood. Radical changes are needed. You, of course, know Rockefeller, chairman of the American Board, and Macintosh, Brassey-Brunel's agent in charge of the construction at the American end. Both have agreed, in the course of the greater good, that they will step down. The two positions will be combined into one and you will be nominated tonight to fill it."

"Good God!" Washington gasped. "May He approve and be on our side. Our first consideration was that the candidate be a good engineer, and you are that. We know you will do the work. The second is that you are a Colonial, one of their own people, so the operation has a definite American ring to it. I realize that there are some among the Tories who hold your family name anathema, we must be frank, but I feel they are in a minority. Our hope is that this appointment and your efforts will spur the lagging sales of bonds that will permit the operation to continue. Will you do it?"

"I gave my word, I will not withdraw it now. But there will be difficulties . . ."

"A single difficulty, and you can put the name to it."

"Sir Isambard. The design of the tunnel is all his, the very conception indeed. I am just an employee carrying out his orders as is his agent Macintosh, who is not even an engineer. If I am to assume this greater responsibility, I will be something close to his equal in all matters. He is not going to like it."

"The understatement of the century, my boy. He has been sounded out cautiously already with the predictable results." A light flashed on the desk and was accompanied by a soft beeping sound. "The Board has returned after their dinners and I must join them since no one is to know I have seen you. If you will be so kind as to wait in the library, you will be sent for. If matters go as we have planned, and they will since we have the votes, you will be sent a note outlining these proposals and then called before the Board. There is no other way."

The door opened at a touch of a button on the desk and Washington found himself back in the library.

There was a soft leather armchair there that he sank into gratefully and when, a few minutes later, Drigg came to inquire if he needed anything he was deep in thought and roused up only long enough to shake his head in the negative. For this was without a doubt the pinnacle of his career—if only he could scale it. Yes, he could, he had no doubts about that, had been without doubts since he had left Mount Vernon for the last time, waving good-bye to his mother and sister at the gate of the simple cottage that was their ancestral home. A cottage that had been built in the shadow of the ivy-grown ruins of that greater house burnt by the

Tory mobs.

He was already an engineer then, graduated first in his class from M.I.T. despite the dishonor attached to his name—or perhaps because of it. Just as he had fought many a dark and silent battle with his fists behind the dorms so had he fought that much harder contest in school to stay ahead, to be better, fighting with both his fists and his mind to restore honor to his family name. After graduation he had served his brief stint in the Territorial Engineers—without the R.O.T.C. grant he would never have finished college—and in doing so had enjoyed to its utmost his first taste of working in the field.

There had been the usual troubles at the western frontier with the Spanish colonies so that the Colonial authorities in New York had decided that a military railroad was needed there. For one glorious year he had surveyed rights of way through the impassable Rocky Mountains and labored in the tunnels that were being driven through the intractable rock. The experience had changed his life and he had known just what he wanted from that time on. Along with the best minds from all the far-flung schools of the Empire he had sat for the prestigious George Stephenson scholarship at Edinburgh University and had triumphed. Acceptance had meant automatic entrance into the higher echelons of the great engineering firm of Brassey-Brunel and this, too, had come to pass.

Edinburgh had been wonderful, despite the slightly curled lips of his English classmates towards his colonial background, or perhaps because of this. For the first time in his life he was among people who attached no onus to his name; they could not be expected to remember the details of every petty battle fought at the fringes of their Empire for the past four hundred years. Washington was just another colonial to be classified with Hindoos, Mohawks, Burmese, Aztecs and others and he reveled in this group anonymity.

His rise had been brief and quick and now he was reaching the summit. Beware lest he fall when his reach exceeded his grasp. No! He knew that he could handle the engineering, drive the American end of the tunnel just as he was driving the British one. And though he was aware that he was no financier he also knew how to talk to the men with the money, to explain just what would be done with their funds and how well invested they would be. It would be Whig money he was after—though perhaps the Tories would permit greed to rise above intolerance and would climb on the bandwagon when they saw the others riding merrily away towards financial success.

Most important of all was the bearing this had upon a more important factor. Deep down he nursed the unspoken ambition to clear his family name. Unspoken since that day when he had blurted it out to his sister Martha and she had understood, when they had been no more than children. Everything he accomplished, in some manner, reflected on that ambition, for what he accomplished in his own name was also done in the name of that noble man who had labored so hard for his country, who in return for his efforts was felled by a volley of English bullets.

"Captain Washington, Captain Washington, sir."

The voice penetrated the darkness of his thoughts and as it did he realized he had been hearing it for some time and not heeding. He started and took the envelope that Drigg held out to him, opened it and read it, then read it a second time more slowly. It was as Lord Cornwallis had said, the motion had been passed, he was being offered the post.

"If you will come with me, sir."

He rose and brushed the wrinkles from his waistcoat and buttoned his jacket. With the note still in his hand he followed the secretary to the boardroom to stand at the foot of the long dark table. The room was silent, all eyes upon him, as Cornwallis spoke from his place at the head of the table.

"You have read and understood our communication, Captain Washington?"

"I have, sir. It appears to be a request to fill, in a single capacity, the dual positions now occupied by Sir Winthrop and Mr. Macintosh. You indicate that these gentlemen approve of the change?"

"They do."

"Then I am most pleased to accept—with but one reservation before I do. I would like to know Sir lsambard's feelings on the change." It was the waving of a red flag to a bull, the insulting of the Queen to a loyal Englishman, the use of the word frog to a Frenchman. Sir Isambard Brassey-Brunel was on his feet in the instant, leaning both fists hard on the polished rosewood of the table, fire in his eye and white anger in the flare of his nostril. A small man before whom, in his anger, large men trembled, yet Washington was not trembling because perhaps he was not the trembling type.

A study in opposites they were, one tall, one slight, one middle-aged and smooth of skin whose great breadth of forehead grew greater with the passing days, the other with a forehead of equal magnitude but with a face browned and lined by sun and wind. A neatly turned out English gentleman from the tips of his polished, handcrafted boots to the top of his tonsured head—with a hundred guineas of impeccable Savile Row tailoring in between. A well-dressed Colonial whose clothes were first class yet definitely provincial, like the serviceable and rugged boots intended more for wear than show.

"You wish to know my feelings," Sir Isambard said, "you wish to know my feelings." The words were spoken softly yet could be heard throughout all of that great room and perhaps because of this gentleness of tone were all the more ominous. "I will tell you my feelings, sir, strong feelings that they are, sir. I am against this appointment, completely against it and oppose it and that is the whole of it."

"Well then," Washington said, seating himself in the chair placed there for his convenience, "that is all there is to it. I cannot accept the appointment."

Now the silence was absolute and if a silence could be said to be stunned this one certainly was. Sir lsambard was deflated by the answer, his anger stripped from him, and as anger, like air from a balloon, leaked from him he also sank slowly back into his seat.

"But you have accepted," Cornwallis said, baffled, speaking for all of them.

"I accepted because I assumed the Board was unanimous in its decision. What is proposed is a major change. I cannot consider it if the man by whom I am employed, the master architect of this construction, the leading engineer and contractor in the world, is against it. I cannot, in all truth, fly in the face of a decision like that."

All eyes were now upon Sir Isambard whose face was certainly a study worth recording in its rapid changes of expression that reflected the calculations of the mighty brain behind it. First anger, giving way to surprise, followed by the crinkling forehead of cogitation and then the blankness of conclusion ending with a ghost of a smile that came and went as swiftly as a passing shadow.

"Well said, young Washington; how does it go? You shall not speak ill of me, I am your friend, faithful and just upon you. I detect the quality of your classical education. The burden of decision now rests upon my shoulders alone and I shall not shirk it. I have the feeling that you know more of these matters than you intimate; you have been spoken to or you would not be so bold. But so be it. The tunnel must go through and to have a tunnel we apparently have to have you. I withdraw my objections. You are a good enough engineer I must admit and if you follow orders and build the tunnel to my design we will build well."

He reached out his small, strong hand to take up a glass of water, the strongest spirit he ever allowed himself, while something like a cheer echoed from all sides. The chairman's gavel banged through the uproar, the meeting was concluded, the decision made, the work would go on. Sir Isambard waited stolidly to one side while the members of the Board congratulated Washington and each other and only when the engineer was free did he step to his side.

"You will share a cab with me." It was something between a request and a command.

"My pleasure."

They went down in the lift together in silence and the porter opened the door for them and whistled for a cab. It was a hansom cab, two wheeled, high, black and sleek, the driver perched above with the reins through his fingers, these same reins leading down to one of the newfangled conversions that were slowly removing the presence of the horse from central London. Here there was no proud, hig

h-stepping equine frame between the shafts, but instead a squat engine of some sort whose black metal, bricklike form rested upon three wheels. The single front wheel swiveled at a tug upon the reins bringing the hansom up smartly to the curb, while a tug on another rein stopped the power so it glided to a halt.

"An improvement," Sir Isambard said as they climbed in. "The horse has been the bane of this city, droppings, disease, but no more. His replacement is quiet and smoothly electric powered with no noise or noxious exhaust like the first steam models, batteries in the boot—you will have noticed the wires on the shafts. Close that trap because it is private, no eavesdropping we want."

This last was addressed to the round and gloomy face of the cabby who peered down through the opening from above like a misplaced ruddy moon.

"Begging your pardon, your honor, but I've not heard the destination.'

"One hundred and eight Maida Vale." The slam of the hatch added punctuation to his words and he turned to Washington. "If you had supposed you were returning with me to my home dispel yourself of the idea at once."

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

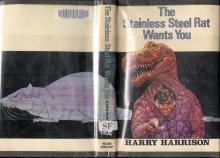

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

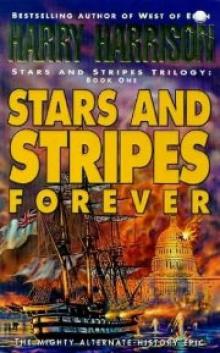

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

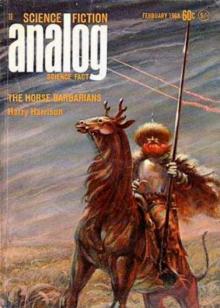

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

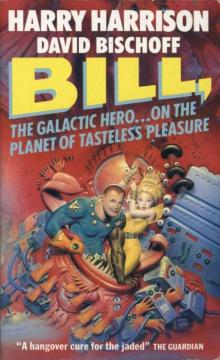

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures