- Home

- Harry Harrison

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 Page 21

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 Read online

Page 21

Paisley pulled the body into the alleyway. Wiped the big clasp knife on the dead man’s clothes, folded it and put it away. Groped through the dead man’s jacket pockets until he found his envelope, clutched it and smiled into the darkness, then hurried away. Only stopping for a moment under the streetlight to check its contents. Grunted in satisfaction.

“This is too much silver for you, wee man. You would only have wasted it.”

His footsteps died away and the street was silent again.

THE REFORMATION OF THE SOUTH

It was late afternoon before all the pieces fell into place for Gustavus Fox. The Pinkerton agent who was stationed in the War Department building had handed in a report about one of the clerks being noted in suspicious circumstances. This had eventually ended up on Fox’s desk. The agent had followed the suspect to a drinking house where he met a third party. The report ended there. It was filed and almost forgotten until the early edition of the newspaper arrived. One of his filing clerks brought it to Fox’s attention.

“One of the War Department clerks, a Giorgio Vessella, was found dead under suspicious circumstances. The suspicion being that he was murdered, since he died of a stab wound and no weapon was found.”

“What was that name?” Fox asked, suddenly attentive. “And get me the last report from agent Craig.”

They were the same. The clerk and the murder victim. The hurriedly summoned Craig amplified his report.

“Yes, sir. I followed him because one of the other clerks was suspicious about him. Like I said in the report, he met another man. Gray-haired, stocky build the stranger had.”

“Have you ever seen him before?”

“Never, Mr. Fox, but I’ll tell you something else about him. I walked by and heard them talking, then later I spoke with the barman. I was right — he had a thick Scotch accent.”

So far there were just suspicions. Too many suspicions and he did not like it. A clerk in the copying section, handling vital documents of war. His blood ran cold at the thought of it. He went to the office where he asked for an emergency interview with Secretary of War Stanton. The wait was a short one; he still paced the floor like a caged animal until he was shown in.

“One of your copying clerks has been killed, murdered.”

“This is terrible. Do they know who did it?”

“We have our suspicions. But I will need your help to find out more about it. I could go through the proper channels but that would take too much time. No one in the copying section knows who I am. And this investigation must be carried out at once. Would you mind going with me now so we can find out what is going on?”

“No, of course not.”

Stanton’s presence opened all of the locked doors and, eventually, took them to the heart of the copying section. They sent for the clerk, Anderton, who had made the original complaint. He was visibly upset.

“The Pinkerton agents. They came and talked to us once. Told us to keep our eyes open and let them know if we saw something suspicious. I told them about Giorgio — and now he’s dead. Do you think he was killed because I went to the agent?”

“We have no way of knowing yet. But if you had your suspicions then you did the correct thing — whatever the outcome. Now, what did you observe?”

“It was the room where we copy only the absolute top secret orders. I came back from lunch and I saw Giorgio at the door and he had his hand on the key. He said that he saw that the door was unlocked and that he was just locking it for me. But, like I said — I was just coming in from the hall door. There is, well, a chance he might have been in the office and was on the way out of it when I saw him.” Fox saw that Anderton was sweating and he did not like it.

“Who is responsible for keeping that door locked?”

“I am, but—”

“Could Giorgio have been telling the truth? Could the door have been left unlocked?”

“There is always that possibility,” Anderton answered in a low voice.

“Then let us now go and see if anything is missing from that room.”

“I’m not authorized…”

“But I am, young man,” Stanton said sternly. “Open it up.”

Their suspicions were horribly justified when a careful count uncovered the fact that one of the envelopes containing the secret orders was indeed missing from the locked room. The count came out wrong. The names on all of the envelopes were compared to a master list until the stolen one was found.

“It’s a troop transport, Mr. Fox,” Anderton said. “The Argus.”

“Make another copy of the letter to the Argus and put it with the others,” Stanton ordered. “When are they to be delivered?”

“In three days’ time.”

Stanton and Fox looked at each other in stunned silence. Were the invasion plans to be betrayed even before they had begun?

Things moved a good deal faster after that. The newspaper artist, that Fox had used before, was sent for and he made a drawing of the mysterious Scotchman from Craig’s description. Copies were quickly printed and distributed to Pinkertons, the police, and other agencies. Fox’s own agents watched the train station, while others went to the Baltimore docks, as well as to all the other nearby ports where ships left for Europe. Fox himself reported to the Secretary of the Navy.

“This is terrible, tragic,” Gideon Welles said. “The orders must be recalled at once.”

“No,” Fox said. “It is too late to do that. And it is also too late to change the invasion plans. And even if we did, the enemy’s mere knowledge of the invasion could prevent us from ever going through with it again. The invasion must go ahead as planned. And we must use all our resources to find and stop this man.”

“And if you fail?”

Fox drew himself up and when he spoke his voice was most grim. “Then we must pray that the invasion is under way before the enemy discovers our ruse. Communication is difficult with Britain and there is little time left for this spy to report to his masters.”

“Pray, Mr. Fox? I am always uneasy when success or failure depends upon summoning the Almighty. You must find that man — and you must stop him. That is what you must do.”

The train was almost on time when it pulled into the station in Jackson, Mississippi. During the war the trains had been up to twelve hours late, plagued by lack of rolling stock and the desperate shape of the roadbed. Peace had changed all that. The newly built train works in Meridian was turning out passenger cars and boxcars to replace the ancient cars dilapidated by the war. More important, federal grants to the railroads in the South had provided needed employment for newly freed slaves. Work gangs had leveled and straightened the rails, smoothing the roadbed with new ballast. Train schedules had become more realistic, the ride almost comfortable.

L.D. Lewis swung down from the last car in the train and seated his bundle carefully on his shoulder. He was a tall man dressed in patched and repaired trousers, wearing as well a faded blue army jacket bereft of any insignia. It had belonged to a sergeant once: the darker blue, that had been concealed from the sun by the stripes, stood out from the faded fabric of the rest of the jacket. Lots of people wore pieces of surplus army uniforms; they were hard-wearing and cheap enough. L.D. did not make a point of mentioning that this was his own jacket, the very one that he had worn throughout the war. There was a mended tear on the left hip where a British bullet had gone through it during the fighting in the Hudson Valley. It matched perfectly the scar in his skin below. He had a wide-brimmed and battered hat that was pulled low over his eyes. Deep, black eyes. Just as black as his skin. He waited until the rest of the passengers, all white, had dispersed before he entered the station. A white ticket agent was talking with a white couple through his barred window. L.D. went on through the station and into the street. An ancient Negro was leisurely sweeping the sidewalk there.

“Morning,” L.D. said. The man stopped sweeping and looked at him quizzically.

“You ain’t from around here?”

/> L.D. smiled. “One word and you can tell all about me. Is that right, old timer?”

“You a Yankee?”

“I sure am.”

“Ain’t never met no black Yankee afore.” He smiled broadly; most of his teeth were missing. “As a fact — ain’t never met no Yankees before. Can I he’p you?”

“Surely. Can you tell me where the Freedmen’s Bureau is?”

The old man’s smile vanished, and he looked around before he spoke. “Jus’ carry on as you goin’. Two, three blocks then you turnin’ right.” He turned away perfunctorily and resumed his sweeping. L.D. thanked him, but his words elicited no response. This was not surprising; the older generation of Negroes in the South saw the Yankees as trouble and wanted nothing to do with them or their laws. He shrugged and walked on.

The Freedmen’s Bureau was at the side entrance of a rundown church, far down a dusty, unpaved street from the center of town. L.D. pushed the door open and stepped inside. It was dark after the glare of the street. Two Negro women were behind a table covered with cardboard boxes filled with papers. They glanced up at him; the younger one smiled, then turned back to her work. A man wearing a reverend’s white collar came in through the door in the back and nodded to him.

“Can I help you, son?”

“Sure can — if you’re the Reverend Lomax.”

“I am.”

“Did you get a letter saying I was coming? Name of L.D. Lewis.”

“We sure did. Mr. Lewis — I’m most glad to see you.” He smiled as he came forward and offered his hand. “Ladies, Mr. Lewis is from the Freedmen’s Bureau in Washington City.”

After the introductions had been made, L.D. put down his bundle and dropped into a chair.

“Can I offer you some refreshment?” Lomax asked.

“Just a glass of water, if you don’t mind.”

He chatted with the two women while the reverend was getting the water. Thanked him and half-drained the glass. “I meant to ask,” he said. “Did a box come for me?”

“Surely enough did. Thought it was for me at first, labeled ‘bibles.’ But it was addressed to you, and said not to open. Not too easy anyway seeing as how it was sealed with riveted leather straps. It’s in the back.”

“Might I see it?” L.D. rose and took up his bundle. Lomax led the way through the main room of the church beyond, and on into a small room at the back.

“Put it here for safe keeping,” he said.

L.D. pushed the long box with his toe, then took a bowie knife from his bundle and used it to cut the straps. Then he started to lever the crate open. “Can anyone hear us in here?”

“No. Just us and the ladies are here today.”

“The letter you wrote to the Freedmen’s Bureau ended up with me.”

Lomax frowned. Sat in a chair and cracked his knuckles abstractedly. “Then you know that we have had trouble here. Nightriders set fire to the church. Lucky I saw it and could put it out in time.”

“Any threats?”

“Some. Notes pushed under the door. Illiterate ones. Telling us to close up or we would get what was coming to us.”

“We’ve had some bureaus broken into. Two were burnt down. One man dead.”

“I saw that in the paper. Can you help us?”

“That’s what I’m here for, reverend.”

He turned again to the crate, levering off the boards that sealed it.

“Will the Bibles really help?” Lomax asked, looking at the red Bibles that apparently filled the crate.

“This kind of Bible will,” L.D. said as he took out the top row of books and pulled up a greased-paper wrapped bundle. He unwrapped the paper and took out the rifle inside. “This is a twenty-shot, breech-loading, Spencer rifle. I couldn’t very well carry it down here on my shoulder, so I sent it on ahead.” He removed a box of ammunition from the crate.

Lomax shook his head and frowned.

“I am a man of peace, Mr. Lewis, and abhor violence.”

“As do I, sir. But we must defend ourselves against these nightriders. They are cowards — but they are becoming bolder every day. And they are wonders at beating old folk, women and children. In South Carolina they actually whipped a woman who was one hundred and three years of age. We are simply defending ourselves against men who seek to return us to slavery. Doesn’t the Bible say something about an eye for an eye?”

“The Bible speaks of peace as well, and of turning the other cheek.”

L.D. shook his head. “That’s not for me. I fought in the war. People think I bought or stole this old jacket, but it was Uncle Sam what gave it to me. I fought for the Union — and now I fight to hold onto that freedom that brave men died in the defense of. So you tell your people not to worry about this church, tell them to get some sleep of nights now. I think I’ll bed down here for a few days, just to make sure these nightriders don’t cause any trouble. One other thing — how is your school going?”

The reverend lowered his eyes: his shoulders sagged. “Not going at all, I am most unhappy to say. We did have Mrs. Bernhardt, a widow-lady from Boston. She worked so hard, with the children during the day, then at night she taught the grown-up folk who wanted to learn their letters. But — you see, people around here didn’t like us learning to read and write. First she had to leave the rooming house, then they wouldn’t let her stay at the hotel, not even that one down by the station. In the end they spoke to her. Never did learn what they said, but she cried all night. Took the train out next day. People here do miss that Mrs. Bernhardt.”

“Well I may not look it, but I was set to be a teacher before the war started. Had a couple of months in school before I went into the army. Should be good enough to teach people their letters.”

“You are a gift, indeed!” the reverend said heartily. “If we eliminate the scourge of illiteracy from our people — why we can be anything, do anything.”

“I do hope that you are right.” He tried to keep the edge of bitterness from his words. He knew far too much about the world the white man lived in to expect any swift miracles.

It had been a long train ride and a tiring one. The seat had been too uncomfortable to get much sleep in. But one thing that L.D. Lewis had learned in the army was the ability to sleep anywhere — at any time. The wooden floor of the storeroom, with his bundle for a pillow, was just about as comfortable as a man could want.

He awoke some hours later to the sound of hymn-singing. Mighty pretty it was too. He hummed along with it for a bit. Then rose and went into the little church and joined the service. Reverend Lomax saw him come in and saw fit to mention him after his sermon.

“Before I say ‘Amen’ I want you all to meet Mr. L.D. Lewis who has come here from Washington City, on behalf of the Freedmen’s Bureau. He is a teacher, yes he is, and he is going to teach you all all about reading and writing.”

There was quick applause and warm smiles of greeting. After the amens more than one offer of an evening meal came his way; he accepted gladly. Later, his stomach filled with grits and dandelion greens, pork belly and red gravy, he made his way back to the church just as it was growing dark. Reverend Lomax had waited for him.

“Front and back doors, they got bolts so they can lock from the inside. That’s my house down the path if you want me.”

“You get a good night’s sleep. I’ll be fine.”

It was a quiet night — and a restful one. The only sounds the deep moaning of the train whistles in the distance and a hunting owl hooting from the trees outside. When he grew sleepy he walked around the church, silently in the darkness, the Spencer rifle always at his side. Looking from each window in turn. But it was a quiet night. Dawn came and the church and the Freedmen’s Bureau were undisturbed.

Twelve newly washed and brushed children turned up for school in the morning. He found the McGuffey’s Readers, untouched since Mrs. Bernhardt had left them. He dusted them off and held his first class. After that he slept most of the afternoon, ate another dinner with

a different family, spent another night on guard.

The third night, a Saturday night, was very different. Just after midnight he heard the quick sound of hoofbeats thudding down the road, getting closer. They appeared to stop in front of the church. L.D. had been looking out a window in the back and he quickly, and silently, made his way to the window in the front office. Staying concealed in the shadows he could see — and hear — through the partly open window everything that transpired in the street outside.

He levered a cartridge into the Spencer rifle when he saw in the light of the lanterns they carried that all of the riders, but one, wore white hoods over their heads that masked their features.

The unmasked man was tied into his saddle, a black man, his face twisted with fear.

“You really sweating, boy,” one of the men said, leaning out and prodding the man in the ribs with his rifle. “You now thinking that maybe you was wrong in the way you acted to your massah.”

“I ain’t done nothing…” He grunted with pain as the rifle was thrust suddenly into his stomach.

“You speaking the truth there. You ain’t done nothing, that’s the truth. Your massah’s cotton growing rotten in the fields, while you and the other niggers sitting around in the shade—”

“No, suh. We ready to work. But what he want to pay us we can’t live on. We starvin’, our chillun can’t eat, suh.”

There was no humor in the harsh laughter. “Maybe you should have stayed a slave — at least you done et well then. But you don’t worry about that, hear. You gonna carry a message to the other darkies. You gonna tell them to get back to work or they end up just like you. Now — get that rope over the beam there.”

One of the masked men kicked his horse forward and threw a rope over the supporting beam of the church’s portico.

Then he tied a noose in the end.

“Get some coal oil on the church — it gonna light this boy’s way to hell.”

A corked jug was loosened from a saddlebow and passed forward. The noose was going around the terrified man’s neck.

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

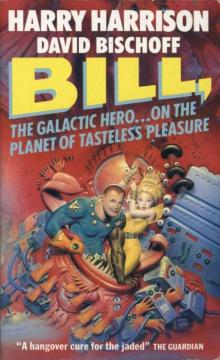

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures