- Home

- Harry Harrison

Wheelworld Page 2

Wheelworld Read online

Page 2

“They’ve been in that meeting and going at it for over two hours now, going over the same ground again and again. They should be tired.” He rose to his feet.

“What will you do?” she asked.

“What must be done. The decision cannot be put off any longer.”

She took his hand briefly in hers, letting go quickly, as though she understood what the touch of her skin did to him. “Good luck.”

“It’s not me that needs the luck. My luck ran out when I was shipped from Earth on a terminal contract.”

She could not go with him, because this was a meeting of the Family Heads and the technical officers only. As Maintenance Captain he had a place here. The inner door to the pressurized dome was locked and he had to knock loudly before the lock rattled and it opened. Proctor Captain Ritterspach looked out at him suspiciously from his narrow little eyes.

“You’re late.”

“Shut up, Hein, and just open the door.” He had very little respect for the Proctor Captain, who bullied those beneath him in rank, toadied to those above.

The meeting was just as demoralized as he had expected. Chun Taekeng, as Senior Elder, had the chair, and his constant hammering and screaming when he was ignored did nothing to help quiet things. There was cross talk and bitter denunciation, but nothing positive was being proposed. They were repeating the same words they had been using for over a month, getting no place. The time had come.

Jan walked forward, holding up his hand for attention, but was ignored by Chun. He walked closer still until he stood before the small man, looming over him. Chun waved him away angrily and tried to peer around him, but Jan did not move.

“Get out of here, back to your seat, that is an order.”

“I am going to speak. Shut them up.”

The voices were dying down, suddenly aware of him. Chun hammered loudly with the gavel, and this time there was silence.

“The Maintenance Captain will speak,” he called out, then threw the gavel down with disgust. Jan turned to face them.

“I am going to tell you some facts, facts you cannot argue with. First—the ships are late. Four weeks late. In all the years the ships have been coming, they have never been this late. Only once in all that time have they been more than four days late. The ships are late and we have used up all our time waiting. If we stay we burn. In the morning we must stop work and begin preparations for the trip.”

“The last corn in the fields … .” someone shouted.

“Will be burned up. We leave it. We are late already. I ask our Trainmaster Ivan Semenov if this is not true.”

“What about the corn in the silos?” a voice called out, but Jan ignored that question for the moment. One step at a time.

“Well, Semenov?”

With reluctance the gray head nodded solemnly. “Yes, we must leave. We must leave to keep to our schedule.”

“There it is. The ships are late, and if we wait any longer we will die waiting. We must begin the trip south, and hope they will be waiting for us when we get to Southland. It is all we can do. We must leave at once, and we must take the corn with us.”

There was stunned silence. Someone laughed briefly, then shut up. This was a new idea, and they were only confused by new ideas.

“It is impossible,” The Hradil finally said, and many heads nodded in agreement. Jan looked at the angular face and thin lips of the leader of Alzbeta’s family, and kept his voice toneless and flat so his hatred of her would not show.

“It is possible. You are an old woman who knows nothing of these matters. I am a captain in the service of science and I tell you it can be done. I have the figures. If we limit our living space during the trip we can carry almost a fifth of the corn with us. We can then empty the trains and return. If we go fast, this can be done. The empty trains will be able to carry two-fifths of the corn. The rest will burn—but we will have saved almost two-thirds of the crop. When the ships come they must have the food. People will be starving. We will have it for them.”

They found their voices and shouted questions at him and at each other, derision and anger on all sides, with the gavel banging unnoticed. He turned his back and ignored them. They would have to talk it out, walk around the new idea and spit on it a bit. Then they might begin to understand it. They were reactionary, stubborn peasants, and they hated anything new. When they quieted down he would speak to them, now he kept his back turned and ignored them, looking at the great map of the planet that hung from the dome, the only decoration in the big hall.

Halvmörk, that’s what the first discovery team had called it. Twilight, the twilight world. Its name in the catalogues was officially Beta Aurigae III, the third planet out and the only one that was habitable of the six worlds that circled the fiercely hot blue-and-white star. Or barely habitable. For this planet was an anomaly, something very interesting to the astronomers who had studied it and entered the facts into their records, and passed on. It was the great axial tilt of the world that made it so fascinating to the scientists, almost habitable to the people who lived there. The axial tilt of forty-one degrees and the long, flattened ellipse of the orbit created a most singular situation. Earth had an axial tilt of only a few degrees, and that was enough to cause the great change in the seasons. The axis is the line about which a planet revolves; the axial tilt the degree that the axis deviates from the vertical. Forty-one degrees is a very dramatic deviation, and this, combined with the long ellipse of its orbit, produced some very unusual results.

Winter and summer were each four Earth years long. For four long years there was darkness at the winter pole, the planetary pole that faced away from the sun. This ended, suddenly and drastically, when the planet turned the brief curve at one end of the elliptical orbit and summer came to the winter pole. The climatic differences were brutal and dramatic as the winter pole became the summer one, to lie exposed to sun for four years, as it had done to the winter darkness.

While in between the poles, from 40 degrees north to 40 degrees south, there was endless burning summer. The temperature at the equator stayed above 200 degrees most of the time. At the winter pole the temperature remained in the thirties and there was even an occasional frost. In the extremes of temperature of this deadly planet there was only one place where men could live comfortably. The twilight zone. The only habitable place on Halvmörk was this zone around the winter pole. Here the temperature varied only slightly, between 70 degrees and 80 degrees, and men could live and crops could grow. Wonderful, mutated crops, enough to feed a half-dozen crowded planets. Atomic-powered desalination plants supplied the water, turning the chemicals from the rich sea into fertilizer. The terrestrial plants had no enemies, because all the native life on the planet was based on copper compounds, not carbon. Each flesh was poison to the other. Nor could the copper based plant life compete for physical space with the faster growing, more energetic carbon forms. They were squeezed out, eliminated—and the crops grew. Crops adapted to the constant, muted, unending light, and unchanging temperature. They grew and grew and grew.

For four years, until the summer came and the burning sun rose above the horizon and made life impossible again. But when summer arrived at one hemisphere, winter fell in the other and there was another habitable twilight zone at the opposite pole. Then it would be possible to farm the other hemisphere for four years, until the seasons changed again.

The planet was basically very productive once the water and the fertilizer were supplied. The local plant life presented no problems. The Earth’s economy was such that getting settlers was no problem either. With the FTL drive, transportation costs were reasonable. When the sums had been carefully done and checked it was clear that food crops could be produced most reasonably, and transported cheaply to the nearest inhabited worlds, while the entire operation was designed to show a handsome profit as well. It could be done. Even the gravity was very close to Earth norm, for while Halvmörk was larger than Earth it was not nearly as dense. Everything

was very possible. There were even two large land masses around the poles that contained the needed twilight zones. They could be farmed turn and turn about, for four years each. It could be done.

Except how did you get your farmers and equipment from zone to zone every four years? A distance of nearly twenty-seven thousand kilometers?

Whatever discussions and plans had been proposed were long since buried in forgotten files. But the few options open were fairly obvious. Simplest, and most expensive, would be to provide for two different work forces. While duplicating machinery and buildings would not be excessively expensive, the thought of a work force loafing in air conditioned buildings for five years out of every nine was totally unacceptable. Unthinkable to work managers who wrung every erg of effort from their laborers with lifetime contracts. Transportation by sea must have been considered; Halvmörk was mostly ocean, except for the two polar continents and some island chains. But this would have meant land transportation to the ocean, then large, expensive ships that could weather the violent tropical storms. Ships that had to be maintained and serviced to be used just once every four and a half years. Also unthinkable. Then was there a possible solution?

There was. The terraforming engineers had much experience in making planets habitable to man. They could purify poison atmospheres, melt icecaps and cool tropics, cultivate deserts and eliminate jungles. They could even raise land masses where desired, sink others that were not needed. These latter dramatic changes were brought about by the careful placing of gravitronic bombs. Each of these was the size of a small building, and had to be assembled in a specially dug cavern deep in the ground. The manner of their operation was a secret carefully kept by the corporation that built them—but what they did was far from secret. When activated, a gravitronic bomb brought about a sudden surge of seismic activity. A planet’s crust would be riven, the magma below released, which in turn brought about normal seismic activity. Of course this could only be effective where the tectonic plates overlapped, but this usually allowed for a wide enough latitude of choice.

The gravitronic bombs had brought a chain of flaming volcanoes from the ocean deeps of Halvmörk, volcanoes that vomited out lava that cooled and turned to stone to form an island chain. Before the volcanic activity died down, the islands became a land bridge connecting the two continents. After this it was, relatively speaking, a simple matter to lower the tallest mountains with hydrogen bombs. Even simpler still was the final step of leveling the rough-shaped land with fusion guns. These same guns smoothed the surface to make a solid stone highway from continent to continent, reaching almost from pole to pole, a single road 27,000 kilometers in length.

Doing this could not have been cheap. But the corporations were all-powerful, and controlled the Earth’s wealth completely. A consortium could have been formed easily enough, was formed, for the returns would be rich and continue forever.

The forced settlers of Halvmörk were migrant farmers with a vengeance. For four years did they labor, raising and storing their crop against the day when the ships came. It was the long awaited, highly exciting, most important event in the cycle of their existence. The work ended when the ships signaled their arrival. The standing corn was left in the field and the party began, for the ships also brought everything that made life possible on this basically inhospitable world. Fresh seed when needed, for the mutated strains were unstable and the farmers were not agricultural scientists who could control this. Clothing and machine parts, new radioactive slugs for the atomic engines, all the thousand and one parts and supplies that maintained a machine-based culture on a non-manufacturing planet. The ships stayed just long enough to offload the supplies and fill their holds with the grain. Then they left and the party ended. All the marriages were consummated, for this was the only time when marriage was allowed, all the celebrations finished, all the liquor drunk.

Then the trip began.

They moved like gypsies. The only permanent structures were the machine storage buildings and the thick-walled grain silos. When the partitions had been taken down and the tall doors levered open, the trucks and copters, the massive harvesters, planters and other farm machinery were wheeled inside. With their vitals cocooned and their machinery sealed in silicon grease, they would wait out the heat of the summer until the farmers returned the following fall.

Everything else went. The assembly hall and the other pressurized dome structures were deflated and packed away. When the jacks were retracted, all the other narrow, long buildings settled onto the springs and wheels beneath them. The women had been canning and storing food for months, the slaughter of the sheep and cows had filled the freezers with meat. Only a few chicks, ewe lambs and cow calves would be taken; fresh herds and flocks would be raised from the sperm bank.

When everything was in place the farm tractors and trucks would haul the units into position to form the long trains, before being mothballed and sealed into the permanent buildings and silos themselves. The engines, the main drive units, would be unjacked after four years of acting as power plants, and would rumble into place at the head of each train. With the couplings and cables connected, the train would come to life. All the windows would be sealed and the air conditioning switched on. It would not be turned off again until they had reached the twilight zone of the southern hemisphere, and the temperatures were bearable again. The thermometer could easily top 200 degrees when they crossed the equator. Though the night temperatures sometimes fell as low as 130 degrees this could not be counted upon. Halvmörk rotates in eighteen hours, and the nights are too short for any real temperature drop.

“Jan Kulozik, there is a question for you. Your attention here, Kulozik, that is an order!” Chun Taekeng’s voice was beginning to crack a bit after a good evening of shouting.

Jan turned from the map and faced them. There were a lot of questions but he ignored them all until the noise died down.

“Listen to me,” Jan said. “I have worked out in detail what must be done, and I will give you the figures. But before I do you must decide. Do we take the corn or not, it is just that simple. We must leave, you cannot argue about that. And before you decide about the corn, remember two things. If and when the ships come they will need that corn because people will be starving. Thousands, perhaps millions, will die if they do not get it. If we do not have that corn waiting, their lives will be on our heads.

“If the ships do not come, why then we will die too. Our supplies are low, broken parts cannot be replaced, two of the engines already have lowered output and will need refueling after this trip. We can live for a few years, but we are eventually doomed. Think about that, then decide.

“Mr. Chairman, I ask for a vote.”

When The Hradil rose and signaled for attention, Jan knew that it would be a long, dragged-out battle. This old woman, leader of the Mahrova Family, represented the strength of reaction, the force against change. She was shrewd, but she had the mind of a peasant. What was old was good. what was new was evil. All change worsened things, life must be immutable. She was listened to with respect by the other leaders, because she voiced best all their unreasoned and repetitious rationalizations. They settled down when she stood, ready for the calming balm of stupidity, the repeating as law of age-old, narrow-minded opinion.

“I have listened to what this young man has said. I value his opinion even though he is not a leader, or even a member of one of our families.” Well done, Jan thought. Take away all my credentials with your opening words, sound preparation to destroy the arguments.

“Despite this,” she continued, “we must listen to his ideas and weigh them on their own merit. What he has said is right. It is the only way. We must take the corn. It is our ancient trust, the reason for our existence. I ask for a vote by acclamation so no one can complain later if things do not go right. I call upon you all to agree to leave at once, and to take the corn. Anyone who does not agree will now stand.”

It would have taken a far stronger individual than

any of those present to rise to his feet before that cold eye. And they were confused. First with a new idea, something they thought very little of at any time, much less at a time when the decision was one upon which their lives might depend. Then to have this idea supported by The Hradil, whose will was their will in almost every way. It was very disturbing. It took some thinking about, and by the time they had thought for a while it was too late to stand and face the woman so, with a good deal of irritated muttering, and some dark looks, the measure was carried by acclamation.

Jan did not like it, but he could not protest. Yet he was still suspicious. He was sure The Hradil hated him as intensely as he hated her. Yet she had backed his idea and forced the others into line. He would pay for this some time, in some way he could not understand now. The hell with it. At least they had agreed.

“What do we do next?” The Hradil asked, turning in his direction but not facing him squarely. She would use him but she would not recognize him.

“We put the trains together as we always do. But before this is done the leaders here must make lists of nonessentials that can be left behind. We will go over those lists together. Then these items will be left with the machinery. Some of them will be destroyed by the heat, but we have no alternative. Two cars in every train will be used for living quarters. This will mean crowding, but it must be done. All of the other cars will be filled with corn. I have calculated this weight and the cars will carry it. The engines will go slower but, with proper precautions, they can move the trains.”

“The people will not like it,” The Hradil said, and many heads nodded.

“I know that, but you are the family leaders and you must make them obey. You exercise authority in every other matter, such as marriage,” he looked pointedly at The Hradil when he said this, but she was just as pointedly looking away. “So be firm with them. It is not as though you are elected officials who can be replaced. Your rule is absolute. Exercise it. This trip will not be the easy, slow affair that it always has been. It will be fast and it will be hard. And living in the silos in Southtown will be uncomfortable until the trains return a second time. Tell the people that. Tell them now so they cannot complain later. Tell them that we will not drive the five hours a day as we have always done before, but will go on for at least eighteen hours a day. We will be going slower and we are late already. And the trains must make a second round trip. We will have very little time as it is. Now there is one other thing.”

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

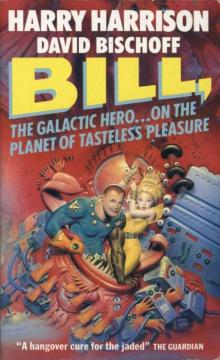

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures