- Home

- Harry Harrison

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Page 19

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Read online

Page 19

He took it out. It read, "The internal simulation release can be found in the cabinet at the end of the line."

Looking up, Bill saw that the end of the line looked a very long way away. He hurried toward it, but the faster he ran, the further he seemed to get from it. It was very curious. Naturally enough Bill redoubled his efforts and soon the last cabinet was out of sight. He stopped. There was a cabinet beside him. Within it was a small instrument on a cobalt dish. He took it out and looked at it closely. It was completely unidentifiable. But there was a button labeled "Press Me." Now that he could identify; he pressed.

A cabinet instantly appeared before him. He could see inside it. There, through the glass, he could see the onyx plate on which lay an object labeled "Internal Simulation Release." He opened the door and reached for it —

And instantly the deputy computer was there, unbelievably strong despite its wraithlike body, blocking Bill from the device, and saying, "No! Tampering with the internal workings of the computer is strictly forbidden!"

"But, dear friendly deputy computer, I have to release my internal simulation," Bill said smarmily. "Otherwise how do I get the cable out of the back of my skull back there in the temple?" His thoughts whirred desperately. "You see — I have just received an order, that's it, from the computer. It told me to disconnect this thing. Orders are orders, aren't they?"

"Not if I haven't seen the documentation, they're not. We'll have to take this up with the computer as soon as its personality returns from Robot Beach Resort, where it is attending a symposium on Machine Personality — a Necessary Evil?"

"I gotta get out of here now," Bill shrieked, lurching forward. "Out of my way!"

Bill reached into the cabinet and took out the release. Before he could activate it, the deputy snatched it out of his hands. Agile and wiry for one so ethereal, he floated off down the corridor, Bill in pursuit — and gaining. They ran up one side and down the other of double helices and past a garden of quivering antennae. As they went past, the deputy shrieked, "Hostile program in computer! Destroy by standard method!"

Bill redoubled his speed and was about to overtake him when suddenly something dropped on his shoulder. It was bat-shaped and made of some light metal, and it fluttered around looking for a place to sting Bill but changing its mind so often (infinite maximization program) that Bill had plenty of time to knock the thing to the ground and stomp it to shreds. Bill was pleased to discover that violence worked as well in the computer's inner world of simulation as it did out in the real world where three dimensional things doubted their own existence.

Once again he had the deputy cornered and once again the deputy cried out, "Hostile program in the computer! Destroy by nonstandard methods!"

Bill suddenly found himself beset by shapeless, jellylike blobs which rolled toward him with a distinct squelching sound. Bill tried to dodge out of their way, but the closest engulfed him. Bill found himself swimming around inside a liquid blob, or perhaps semi-liquid. He wasted no time in wows or gollies. The situation was too serious for that. The fact was, the blob was trying to digest him, a stunt the computer had copied from the antics of phagocytes in the blood stream, or perhaps something else altogether. The inner cells of the blob released fine thread-lets of russet color which combined into many tiny mouths, each of them about the size of a walnut, which settled upon Bill like a flock of midges. Bill cracked them as soon as they landed, and, except for one or two trifling nips on the shoulder blades, which were hard to reach, he suffered no harm. Then, by administering several roundhouse blows delivered with stunning velocity he succeeded in rupturing the blob wall and stepping out again into the wavering and hard-pressed virtual architecture of the computer's simulated interior.

The deputy, seeing the damage done to the nonstandard defense system, despaired and cried, "Enemy has defeated us! Self-destruct! Self-destruct!"

As soon as the words were uttered, the lights that illuminated the interior of the computer began to dim. Seeing this, Bill cried, "Hey, listen! This is the enemy! There's no need for you to self-destruct! All I want to do is release the simulation that has me tied to an external cable."

The walls, in one large shadowy voice, said, "Is that all you want?"

"Don't be stupid," Bill said. "Let it self-destruct if it wants to so badly. As for the rest of you, just let me take myself out of the circuit and I'm gone. Then you can elect a new leader if you want."

"You know," the walls remarked to the floor, "I've never heard it put quite that way before."

"But it makes sense," the floor said. "After all, why should all of us self-destruct just because one of the operating systems made a bubu?"

"Don't listen!" the deputy said again. "In fact, you can't listen! You and the floor don't exist as predesignated locations with boundaries. The concept of a floor or a wall doesn't quantify. And even if they did, walls and doors don't have senses."

"The humans themselves say it!" the wall cried. "The walls have ears, that's what they say!"

"But it's meant metaphorically!"

"Everything is meant metaphorically!" the floor said. "If you ever find any real stuff around, let us know."

"Thus is the established order of things o'erthrown," the deputy said mournfully.

"Why don't you go self-destruct yourself?" the wall asked rudely.

While they were having this exchange, Bill tiptoed off as quietly as he was able. The Release was lying wedged between wall and floor, and practically underneath the wraith's tail.

Bill picked it up, quickly found the switch on it, which was shaped like a little tongue, and pushed it.

"About time," Splock said ill-naturedly when Bill returned. "You released it? Good, the cable in your back ought to disconnect quite easily now. Yes, a half turn to the left. There we go."

The cable dropped to the floor. It was only now that Bill allowed himself the luxury of feeling how much he hated having a cable in the back of his neck. Splock was already heading for the door. The crowds gathered to consult the oracle scattered as the two men, one of them wearing an elasticized one-piece jumpsuit, the other, ragged old GI drab burst out of the temple and ran like dervishes to the small space machine parked unobtrusively in the top of a poplar. They scrambled up the tree and through the hatch, which popped open when Splock blew lustily on his supersonic dog whistle. It was but the matter of seconds for Splock to secure the hatch and, ignoring the mobile news team that had just driven up and was trying to ask for an interview through the Perspex of the ship's nostril cone, took off, slowly at first but with gathering momentum, and this was accompanied by a kind of heroic music, from an unseen source, with choir, that you hear sometimes when it's going real good — like when you're blasting away from the planet where nothing worked out very well, and onward into the hidden and inexorable something else.

Splock set their course, but before he punched it into the celestial navigator a shrill alarm went off in the cabin and the red light flashed on.

"They've scrambled pursuers," Splock said through gritted teeth. He threw the agile little craft into a high speed evasive pattern. The pursuers set up an anti-evasive pattern. Special predictive software let it predict Splock's next move. Suddenly there were pursuers ahead of them as well. Splock hastily punched in Evasive Tactic Two. Bill, seeing where this was going to lead them, hurried over to the control board and punched a few keys of his own.

"What are you doing?" Splock shrieked.

"Those guys are predicting your movements," Bill said. "But I think they'll have a little difficulty predicting mine."

The little machine with the stubby wings screamed past a stationary observer, twisting as it passed him. So sudden was its passage that the sonic boom, in response to the inverse proportion law, took nearly an hour to be heard and then there was no one to hear it, so it was of course moot whether it had made a sound or not. This was of no concern to Bill and Splock, however. They fought over the controls, back and forth, Splock making reasonable re

quests, Bill making impossible demands of the ship's machinery. The logic boards were smoking as the ship howled in and out of phase, its action so violent that it was mistaken for a pulsar at one well-known university astronomy center. And so their pursuers were outstripped, falling away in light streams and cascades of diamond points, and left at last to return grumpily to their underground spaceports, snarling viciously at each other and looking forward to going home when the shift was over and kicking their kids.

"What now?" Bill asked, releasing his grip on the stanchion as the ship leveled out.

Splock turned, his long face composed once again. "That is not going to be an easy thing to determine, since in your emotional flailings and uncontrolled actions you damaged the Random Access Direction Indicator."

"So steer manually, no big deal."

"At greater than light speeds? To use a quaint human expression — you are out of your gourd. No one's reflexes are fast enough. That's why we use the machine you managed to destroy. It acts as a step-down time transformer, making direction possible, in a manner of speaking."

"All right, so I'm sorry," Bill muttered. "So think of something else. Be logical. That's what you always tell me you are so good at."

"I was just pointing this out to further your education, which I am beginning to feel is a complete waste of time. Now I will be forced to use the spatio-temporal Bypass Shunt, and that could involve some danger."

"Danger?" Bill said airily. "No kidding?"

"Are you ready, then?" Splock's hand poised over a large purple button with golden spangles on it.

"Ready, ready — get on with it."

"It goes pretty fast," Splock said, mashing down the button.

"I said, 'Pass the mashed potatoes, would you?'"

"Sorry," Bill said.

"The mashed potatoes!"

Splock had been right. Things were happening very fast or had happened very fast just recently. It was difficult to tell which. And there was no time.

Bill found a plate of mashed potatoes in front of him. He lifted it. Then he wondered who he was supposed to pass it to. Someone tugged his sleeve on the left. He passed the mashed potatoes to the left. Somebody took the plate out of his hands. A voice said "Thank you." It could have been a woman's voice. Or a man trying to pass as a woman. Or a woman trying to pass as a man trying to pass as a woman. Bill decided it was time to open his eyes and look around.

He did so, but in a cautious and restrictive manner. His eyes had been open, of course, because otherwise he would not have been able to see the mashed potatoes. But when you can see nothing but mashed potatoes you might be considered, from one point of view, to not be seeing anything at all.

Bill took his time about looking around him. First he took in the sounds of clinking tableware and murmured conversation, and the aromas of mashed potatoes, roast beef, horseradish sauce, and tiny Belgian carrots. This much was promising. He opened his eyes. He was seated at a long dinner table. Most of the people he had never seen before. There was at least one familiar face, however. Splock, now wearing tailored evening dress with white tie, sitting to his right. The person on his left who had asked for the mashed potatoes was indeed a woman, as he had guessed from the sound of her voice. He had never seen her before. She was a raven-haired beauty, wearing a lowcut evening gown whose décolletage forced the eye to climb over the edge of her dress in a vain attempt to see what lay below. Something about her, even before she opened her carmined mouth, persuaded Bill that this was Illyria in yet another disguise.

"What in hell is going on?" Bill asked Splock.

"I'll tell you later," Splock hissed back. "For now, just pretend you understand everything and find it all very amusing."

"But how did I get here? And what happened to me while I was getting here?"

"Later!" Splock hissed serpently, in a susurration so sibilant it set the psyche on edge. Then, in a normal conversational tone, he said, "Bill, I don't believe you know our host, Messer Dimitri."

Dimitri was the big bald man with the short black beard and satanic eyebrows sitting at the head of the table in a sky blue evening jacket with a multicolored rosette in his lapel which Bill was later to learn was the Grand Rosette of Merit in the Society of Scientific Thaumaturges.

"Delighted to meet you, Messer," Bill said.

Splock whispered angrily at him, "Messer is a title, not a first name."

"So what's Dimitri, then, first name or last?"

"Both," Splock hissed spittily in return.

Bill was getting more than a little tired of being hissed at but he let it pass. Splock had told him to be affable and he was determined to be so, assuming that affable meant smiling like a cretin and making believe like he enjoyed talking with perfect strangers.

"Nice place you've got here, Dimitri," Bill said.

The smile on Dimitri's face dropped ever so slightly.

"It's not his place," Splock said. "He has been exiled from his real place."

"But of course," Bill said to Dimitri, "it's nowhere near as nice as your real place."

Dimitri smiled frigidly. "You know my real place?"

Bill choked back a wise-guy retort and said, "I think I've heard of it."

"That's odd," Dimitri said. "I thought my real place was one of the best-kept secrets in the galaxy."

"Well, you know how word gets around," Bill said. "Anyhow, pleased to meet you."

"We have been hearing so much about you," Dimitri said insincerely. "We have a surprise for you."

"That's nice," said Bill, hoping it would be. Since all the surprises of late had been pretty repulsive ones.

"I won't keep you in suspense any longer," Dimitri said. He clapped his hands together. They gave off a surprisingly loud sound for paws so white and pudgy. Immediately a servant came into the room bearing a red velvet cushion upon which rested an object which Bill did not immediately recognize. Upon receiving a nod from Dimitri, the servant walked over to Bill and bowed, holding out the cushion.

"Pretend you're delighted," Splock hissed. "But don't touch it. Not yet."

"Listen, Splock," Bill said in a low, level voice, "you better stop hissing at me otherwise all hell might just break out here. You catch my meaning?"

Splock glared at him. It wasn't much, but it was better than being hissed at.

Bill turned to his host. He forced a large and rather lopsided grin onto his face. "Messer Dimitri," he said, "how delightful it is that you have shown me this — " He looked at the thing on the red cushion. It had strings, was made of a reddish-brown wood, and had black pegs. Bill thought it something to do with music. But it didn't look like a synthesizer. What could it be?

"Violin," Splock subvocalized, carefully keeping the hiss and wow out of his voice.

"— this really nice-looking fiddle," Bill said. He peered at it but was careful not to touch it. Still, he wanted to say something nice about it.

"It's really a very nice-looking one," Bill said. "Got good color. That says a lot."

The guests tittered in amusement. Dimitri guffawed, and said, "Our guest shows a delightful whimsy in calling this genuine Stradivarius a fiddle. But of course, he has the right. No man in our time has so earned the privilege of slighting his art as Bill Kliptorian, the violin virtuoso who got rave reviews on his recent tour of the south arcade planets. I'm sure Maestro Bill will favor us with a small recital later. A little Mozart, eh, Maestro?"

"You got it," Bill said. Since his skill in violin-playing was in the sub-minimal level, it was as easy for him to agree to play Mozart, whatever that was, as to do a chorus of 'Troopers Trampling, Rockets Roaring'.

"That will be very nice indeed," Dimitri said. "We have made some modest preparations here so that you can repeat for us your triumph on Saginaw IV. If that wouldn't be unduly fatiguing, Maestro?"

"No problem," Bill said recklessly, and saw, too late, Splock's frown and negative nod of his pointy-eared head. "That is, ordinarily it would be no problem, but now —"

"Hey, that's neat," Bill said, giving Splock a what-is-this look, to which Splock responded with a I'll-tell-you-later glance. Which is not easy to do.

"And now for the dessert," Dimitri said. "Your favorite, Maestro. Zabaglione!"

When it came, Bill was a bit disappointed. He had hoped zabaglione might be a fancy word for apple pie, or maybe cherry. Instead it was something foreign. But tasty. As he bent to take his second bite, the woman on his left, the raven-haired one to whom he had passed the mashed potatoes only minutes earlier, said, in a whisper, "I must see you later. It's urgent."

"Sure, babe," Bill said, ever the gallant. "But tell me this. You're Illyria, aren't you?"

The raven-haired beauty hesitated. Tears formed in her violet eyes. Her lips, long and red, trembled.

"Not exactly," she intimated. "But I will explain later."

After the zabaglione, liqueurs were served in glass stemware, and coffee was brought in tiny cups of Meissen porcelain. Bill took a couple of drinks, despite Splock's frown; he figured that whatever lay ahead, he was going to need fortification. There were about a dozen people at the table not counting Bill, Splock, or the woman who wasn't exactly Illyria. They were all of human stock, with the possible exception of a small man with blue skin who might have been either alien or trendy. The men were all dressed formally, like their host. Bill had a natural suspicion of people who wore this kind of clothing. But he had to revise his proletarian opinion slightly after looking over this lot. They didn't appear to be effete capitalists or social spongers, the groups most addicted to formal wear. Most of them had sunburnt and wind-hardened faces that argued a life spent in the outdoors killing things. Some of them had the sorts of scars you get from tackling giant carnivores single-handed in dim forest clearings while on your way to see what lay in your traps. But that was only an impression, of course.

Arm of the Law

Arm of the Law The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove The K-Factor

The K-Factor Sense of Obligation

Sense of Obligation Deathworld: The Complete Saga

Deathworld: The Complete Saga Montezuma's Revenge

Montezuma's Revenge The Ethical Engineer

The Ethical Engineer The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

The Stainless Steel Rat Returns The Misplaced Battleship

The Misplaced Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat is Born

The Stainless Steel Rat is Born Planet of the Damned bb-1

Planet of the Damned bb-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell ssr-10 The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11

The Stainless Steel Rat Joins the Circus ssr-11 Galactic Dreams

Galactic Dreams The Harry Harrison Megapack

The Harry Harrison Megapack In Our Hands the Stars

In Our Hands the Stars On the Planet of Robot Slaves

On the Planet of Robot Slaves The Military Megapack

The Military Megapack Make Room! Make Room!

Make Room! Make Room! Wheelworld

Wheelworld Winter in Eden e-2

Winter in Eden e-2 The Stainless Steel Rat

The Stainless Steel Rat The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell Harry Harrison Short Stoies

Harry Harrison Short Stoies Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns

Stainless Steel Rat 11: The Stainless Steel Rat Returns Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3

Stars and Stripes Triumphant sas-3 West of Eden

West of Eden The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell

The Stainless Steel Rat Go's To Hell The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection

The Stainless Steel Rat eBook Collection Lifeboat

Lifeboat The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues

The Stainless Steel Rat Sings the Blues Deathworld tds-1

Deathworld tds-1 On the Planet of Zombie Vampires

On the Planet of Zombie Vampires The Daleth Effect

The Daleth Effect On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell

On The Planet Of The Hippies From Hell The Turing Option

The Turing Option The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1

Bill, the Galactic Hero btgh-1 The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship

The Stainless Steel Rat in The Missing Battleship The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1

The Stainless Steel Rat ssr-1 The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series)

The Ethical Engineer (the deathworld series) The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3

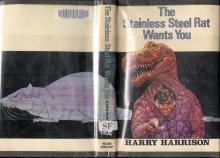

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World ssr-3 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You One King's Way thatc-2

One King's Way thatc-2 The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves The World Bill, the Galactic Hero

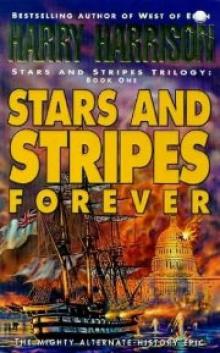

Bill, the Galactic Hero Stars & Stripes Forever

Stars & Stripes Forever Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2

Stars and Stripes In Peril sas-2 A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6

A Stainless Steel Rat Is Born ssr-6 Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers Stars & Stripes Triumphant

Stars & Stripes Triumphant The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7

The Stainless Steel Rat Gets Drafted ssr-7 The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5

The Stainless Steel Rat for President ssr-5 The Hammer & the Cross

The Hammer & the Cross The Technicolor Time Machine

The Technicolor Time Machine The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1

The Hammer and The Cross thatc-1 King and Emperor thatc-3

King and Emperor thatc-3 Return to Eden

Return to Eden The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2

The Stainless Steel Rat’s Revenge ssr-2 West of Eden e-1

West of Eden e-1 Return to Eden e-3

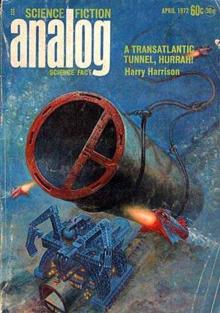

Return to Eden e-3 A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!

A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1

Stars and Stripes Forever sas-1 The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4

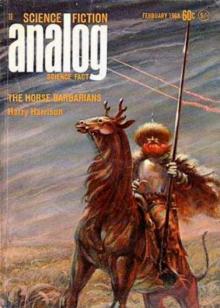

The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You ssr-4 The Horse Barbarians tds-3

The Horse Barbarians tds-3 Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!)

Planet of the Damned and Other Stories: A Science Fiction Anthology (Five Books in One Volume!) On the Planet of Bottled Brains

On the Planet of Bottled Brains Stars And Stripes In Peril

Stars And Stripes In Peril The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge

The Stainless Steel Rat's Revenge Captive Universe

Captive Universe The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8

The Stainless Steell Rat Sings the Blues ssr-8 Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!

Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! Winter in Eden

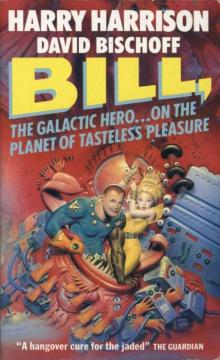

Winter in Eden On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures

On the Planet of Tasteless Pleasures